This article was originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource.

He asked her if she was cold. A wind whips around the park in western Kentucky a couple days before Christmas. He puts his arm around her as they move closer together on the bench.

Blake Livesay, 27, met Laura Brooke, 31, online earlier in 2020, and they’ve been inseparable since. She liked his way with words, “like a walking, talking Hallmark card.” He fell in love with her two kids from a past relationship.

With the hardships they’ve been through this pandemic, the couple said they at least have each other. But their struggles have been crushing for them.

“These past few days and weeks alone has just been driving me more to not want to live because the way this world is,” Livesay said behind his gray mask. “We don’t deserve to be in a situation. Nobody does. I’m saying I’ve got her to think about. And if I feel like I can’t take care of her, then I don’t have nothing to even live for anymore.”

They said they were working at a candle factory in Mayfield, Kentucky, when Brooke fell sick with COVID-19. They said they were fired that summer after being out of work for an extended period of time. They were also evicted from their trailer park around the same time, the couple said, and had to surrender one of their two dogs because they couldn’t take care of it themselves.

They’ve since moved in with people in Murray, Kentucky, that they connected with over Facebook months ago. In lieu of rent for staying there, they contribute food Brooke purchases with her Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, or SNAP.

Since moving to Murray, the couple has been desperately searching for employment and a reliable paycheck, doing interviews with fast food restaurants. But they were worried they may not receive a call back for interviews because their prepaid phone would be shut off the next day and their door of opportunity would close yet again.

“This world just seems like it’s getting darker and colder, no matter how bright the day is,” Livesay said. “I’m ready to jump through that door. But every time that door is even cracked and you get ready to open it to go through, it still gets slammed right in your face. It’s just one thing leading to another. It’s hard.”

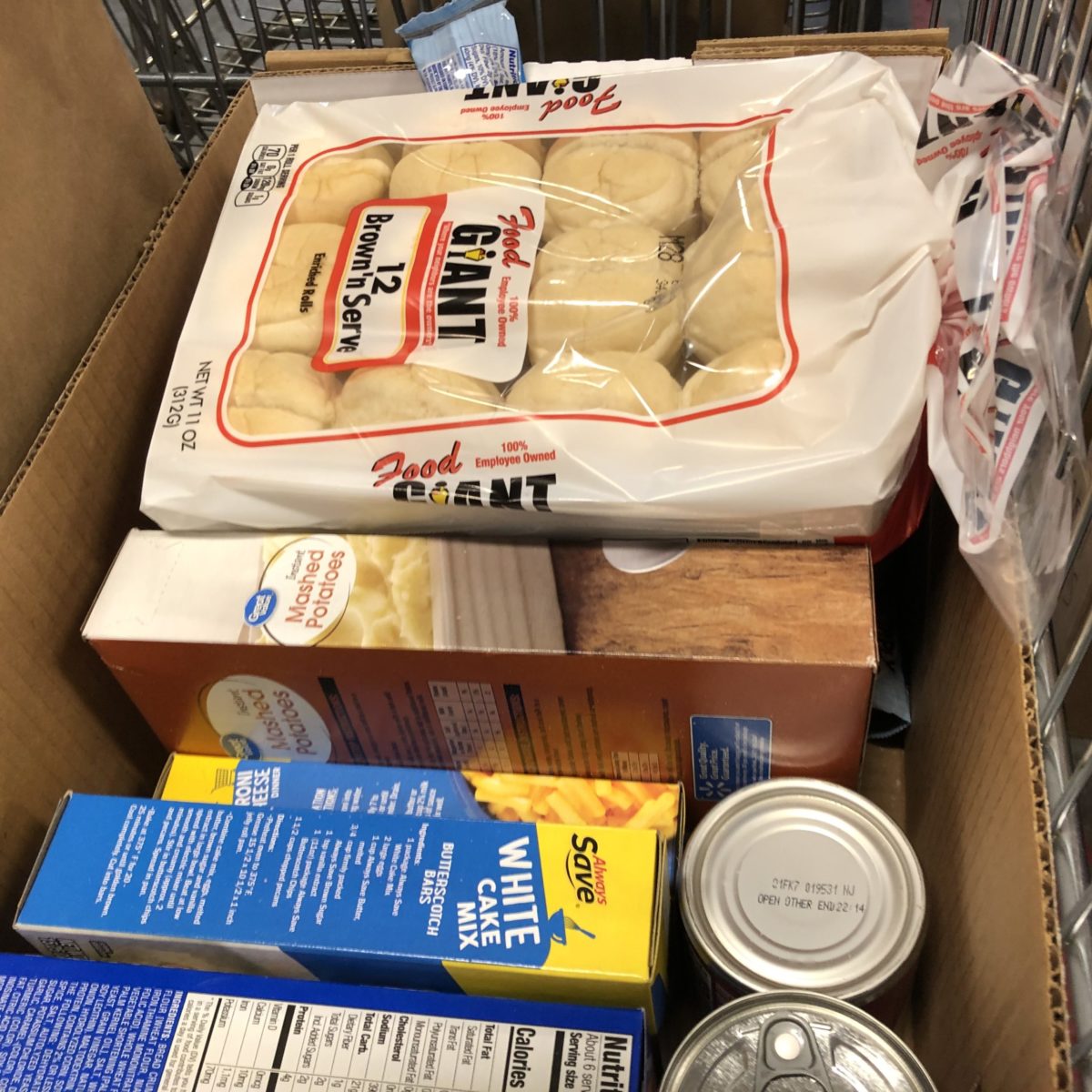

But for Brooke, a bright spot in their dark winter comes in the form of a wooden box across the park next to the skating ramps, filled with rice, spaghetti and canned goods. It’s called a “blessing box,” and it was a new concept for Livesay and Brooke. Take what you need; no questions asked. She’s even taken food she’s bought with her SNAP benefits to put back in the boxes, like canned ravioli that doesn’t need to be cooked. Both of them have been homeless before, and they know others could be facing even greater need than they are.

“I have a big heart. That’s how I’ve always been,” she said. “Other people benefit from what I can put in those boxes, because there are actually some people that are homeless and camping right now.”

Amid their struggles, they believe the government has left them behind in this devastating pandemic. They said they don’t deserve to be on the verge of homelessness, and many others don’t deserve to be homeless either.

Livesay said he voted for President Donald Trump and that he supports the President’s efforts to get a more substantial stimulus check to people. He said the government “doesn’t need to be greedy anymore.”

After months of increasing COVID-19 caseloads and deaths across the country, a second federal COVID-19 relief package was finally signed by Trump, up against a cliff of expiring unemployment benefits and other aid for millions of Americans. In months that it took for a bipartisan deal to emerge, food insecurity, unemployment and hardship hit staggering levels in the Ohio Valley.

One Kentucky community rallied to meet their community’s needs when the government faltered, but some say even more federal aid will be needed in the new year to make it through the end of the pandemic.

Coming Together

Mary Buck considered herself to be just a stay-at-home mom before the pandemic, taking care of her kids and making jewelry in her free time. She didn’t volunteer much around Murray. But when state-mandated shutdowns of schools, indoor dining and more began in the spring of 2020, she decided to do something to get community members what they needed.

She created a mutual aid Facebook group called the Calloway County Collective, where people can post and connect with others about their needs, and others can help fill those needs. The collective has helped people with utility payments, beds for people who lost theirs because their furniture was rented and connections to state agencies to receive unemployment checks.

“The most vulnerable, the ones that had just lost their jobs, who had no savings had no income, at no fault of their own, were left not knowing how to help themselves,” she said.

Buck and her fellow volunteers have also been encouraging and coordinating the construction of blessing boxes throughout the county. At least 10 new boxes have been created this year, several in the poorer, eastern half of the county. There are now more than 30 total in the county, including one being built for pets.

For Buck, the blessing boxes were there to help those in need when the government and other entities were not, during a time when the state unemployment system faltered and demand at food banks soared.

“The need for many things is greater than it has ever been at any point in our lifetime. So there isn’t a structure that can balance that out because it’s never happened before,” she said. “That was the greatest inspiration for the blessing boxes was the fact that there were so many people who needed that help but there was not enough help available anywhere, government or not.”

At the local food pantry in Murray, staff and volunteers prepared about 1,000 packaged meals of turkey, potatoes and rolls for Christmas, the most they’ve ever prepared. The pantry, which also helps with other needs such as utility bills, has received more than 19,000 applications for help this year, roughly 7,000 more than usual.

Federal aid did finally come with the second COVID-19 relief bill, offering $25 billion in rental assistance, $400 million for food banks, and $175 million to programs for seniors such as Meals on Wheels. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention moratorium on evictions was also extended until the end of January.

But in the months that followed the initial massive CARES Act in March, troubling levels of food insecurity have persisted in the Ohio Valley. According to U.S. Census survey data published in mid-December, 423,204 households in Kentucky and 175,553 households in West Virginia have at times not had enough to eat, or nearly 1 in 4 households. In Ohio, nearly 1 in 5 households at times don’t have enough food.

Persistent Needs

Claire Gysegem manages public relations for Hocking Athens Perry Community Action, the organization that runs Southeast Ohio Foodbank. She’s based in Athens County in the state’s eastern Appalachian portion, considered to be one of the poorest counties in Ohio in a region that economically lags behind the rest of the state.

Hunger had always been a constant in Athens County, something Gysegem said formed a mental “scar tissue” for her, something that she lived with. But the unprecedented levels of need she has seen across the country have shaken her.

“I at one point grew up almost used to the idea of hunger being a thing in Athens,” she said. “Now, oh my God, it keeps me awake at night. Because it’s unacceptable. It’s a predicament that millions of people in this country have found themselves in and it is unacceptable.”

She said the Southeast Ohio Foodbank and its affiliate food pantries across the region didn’t see a dramatic spike in demand with the onset of the pandemic but have seen steady demand for food since. Gysegem believes that may be simply a result of the underlying conditions there; Many people in the region were already trying to survive day-by-day before the pandemic.

Yet she still hears gut-wrenching stories from local schools of kids having severe anxiety about seeing their parents go without eating.

“It’s hard to look at the wealth that this country has, and the resources that we have to tackle this problem. But it’s just the fact that it’s not getting to really where it needs to go, and especially for these kids, it is so incredibly frustrating,” she said.

Gysegem said some parts of the new relief bill, including a 15 percent boost to SNAP benefits, are more than welcome, especially with what she sees as added economic benefits for rural grocery stores that receive purchases from SNAP. But she also wonders how much this aid will help people who’ve had months of rent and utility bills pile up.

In Huntington, West Virginia, Cynthia Kirkhart, CEO of the Facing Hunger Foodbank, said her foodbank is still serving about 20 percent more people than usual, which she estimates is around 160,000 people across several counties in West Virginia. She said the multiple crises of people facing evictions, unemployment and food insecurity has been the “perfect storm” this year.

She hopes once the country navigates this pandemic, there will be a closer examination of how to strengthen the social safety net for future emergencies. For her, that means reliable public transportation in her state to better allow people to receive donations from food pantries.

“We’ve talked about transportation for years. What have we done to address it?” she said. “That’s the thing. Getting the full value of the lessons through this horrible, horrible, horrible time.”

Some policy analysts argue that this latest COVID-19 relief bill can only serve as a stopgap measure until the Biden administration comes into office, when there will be need for another massive relief package to get the country through this pandemic and vaccine distribution. Millions of Americans were on the brink of losing unemployment benefits before the recent bill was passed.

“It gives us a little more runway in front of the cliff. And that’s about it. It will not get us as far as we need to go,” said Dustin Pugel, senior policy analyst at the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, a left-leaning think tank. “Congress is going to need to come back and act very quickly in the new year to make sure that we don’t face another cliff in March as we’re staring down right now.”

Pugel believes months-long gridlock in Congress to get another COVID-19 relief package to the country ultimately hurt the economic recovery from the spring shutdowns. And the bill does not include the funding for state and local governments that his group advocated for.

“We waited too long. So this was an absolutely needed situation, this aid package. And I think that history has shown that when the federal government does step up, they can really help a lot of folks,” he said.

In Murray, Brooke and Livesay are hoping for a miracle to get them back on their feet. Brooke worried she would be unable to see her kids this holiday season and that stable housing would begin to help arrange visits with her kids from her ex-husband.

“I’m just hoping that some kind of miracle comes through that we’re able to get a place and a job soon so that we can start rebuilding what we’ve lost,” she said.

The Ohio Valley ReSource gets support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and partner stations.