On a Friday afternoon, the washers and dryers run nonstop at Bream Memorial Presbyterian Church, in Charleston, West Virginia. Three bright-white tiled shower rooms line one wall. MREs – Meals Ready-to-Eat – sit on shelves behind a small wooden reception desk.

On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, the church serves lunch to dozens of people, many of whom struggle with an addiction, are unhoused, or both.

Today, Ben Clemente, a volunteer who’s currently unhoused, hands out turkey and ham sandwiches.

“I’ve served about 25 people,” he says, checking his phone for the time. “By the time we close, I expect to serve 20 more.”

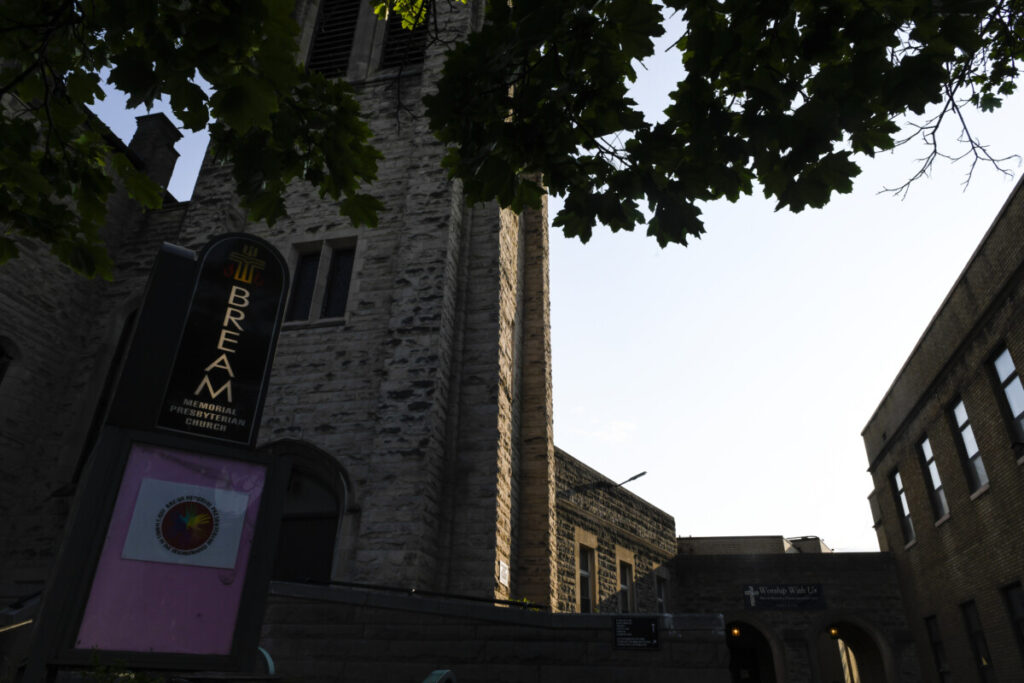

Bream’s gray stone tower, built in the 1890s, anchors West Washington Street on Charleston’s West Side, the city’s most diverse neighborhood. At its economic peak in the 1950s, the area was home to a vibrant multiracial working class, supported by good-paying manufacturing jobs and some of the biggest names in the chemical industry, like Union Carbide and Dow Chemical.

Those jobs steadily disappeared over decades. And discriminatory practices, like redlining and the destruction of 70 acres in the neighborhood to make way for Interstate 64, left significant scars. Boarded-up homes and businesses dot the streets around the church, including a former pharmacy, which recently reopened as a Dollar Tree store.

But even as the number of people in the community and in Bream’s pews on Sunday mornings declined, the glaring needs of the neighborhood called the church to action.

Bream’s work is one facet of a broad faith- and community-based effort to address the shifting contours of this community – to help with everything from food insecurity to addiction.

Among the faith-based organizations that have joined Bream in this effort is the West Side-based Partnership of African American Churches, which describes itself as a nonprofit, faith-based community development corporation that serves all communities, with a focus on African American ones.

These entities have stepped in to fill the void left by a shortage, or absence, of assistance from the local, state and federal government.

“It’s not that we’ve been asked to do this,” says Derek Hudson, executive director of outreach for Bream and a West Side native. “But we see the need, and we’re going to it.”

A church with a proud history

In 1946, Bream’s membership peaked at nearly 3,000. Today, on a typical Sunday, about 40 to 50 people show up to worship. This reflects a nationwide decline in church membership, which recent Gallup polls show has fallen by 20 percent in the past two decades.

But Hudson points out the church’s mission has always been to serve. Glen Elk Mission, founded by Charleston’s First Presbyterian Church in 1883, was located several blocks away from Bream’s current location.

“Mission and outreach were built into this church from the beginning,” he says. While Bream is largely a white church, Hudson notes that Black families have always been part of the congregation. Mildred Bateman, a church member and physician who was appointed director of West Virginia’s Department of Mental Health in 1962, was a mentor to Hudson and the first Black woman appointed to lead a state agency.

Bream’s congregants now meet for weekly worship services in a small chapel rather than the main sanctuary, both to save on utility costs and because a large space is no longer needed. But the church has expanded its community services to meet the increased need.

A lifelong Bream member, Hudson is at once hard to miss and unassuming. Dressed in jeans and brown square-toed cowboy boots, with a salt-and-pepper beard and thick, black-rimmed glasses, he does a little bit of everything at Bream’s ministry center.

Adjacent to the dining area is a room stacked with a range of items – bottled water; hygiene supplies, like combs and toothpaste; and dog food. Upstairs, a well-stocked food pantry includes canned vegetables, pasta and cereal.

Known as the SHOP – Showers, Health Care and Outreach Program – the building that houses the ministry center was built in 1937 to serve as the church’s fellowship hall. Hudson says he has the full support of the church’s congregants.

“Everybody was very positive,” he says, “and they’re the reasons that we can continue to grow, because they want to be a church that really walks the path of Jesus.”

The church also hosts domestic-violence counselors and helps people living on the streets find housing.

The nation’s opioid crisis has hit West Virginia particularly hard, and Charleston has suffered considerable consequences, including an outbreak of HIV the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s prevention chief called “the most concerning in the United States among people who inject drugs.”

Hudson estimates about 60 percent of the people who show up at the SHOP struggle with substance misuse. The church keeps a supply of naloxone on hand, and it also serves as a hub for the city of Charleston’s Coordinated Addiction Response Effort, or CARE, team.

A CARE team peer-support coach spends a few hours several days a week at Bream offering the opportunity for individuals struggling with addiction to get into treatment when they’re ready and, in the meantime, encouragement that their life matters.

Hudson also sees plenty of families who’ve come to rely on the church’s outreach ministry for groceries from its pantry. And the need has grown in the past year as COVID-19 emergency allotments for Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance program have expired. Every SNAP household in 32 states, including West Virginia, has suffered benefit cuts as a result. Coupled with the rising cost of food – grocery prices rose 11 percent from 2021 to 2022 – Hudson says more people in the neighborhood are struggling to make ends meet. The increased demand has forced him to reduce the amount of food the SHOP can distribute to each individual.

“There was never a limit before,” he says. “But right now, we can only give out two bags of groceries [per client] a week.”

For the church’s pastor, the Rev. Dawn Adamy, leading Bream means embracing the outreach vision of the church. And she’s all in. “I really feel like the Holy Spirit kind of blew me here, blew us together,” she says.

Adamy came to the church in the fall of 2019, six months before COVID-19 struck. The pandemic, she says, set Bream on course to launch the SHOP. “We were approached at that time because we had a gym and would we be willing to be an overflow warming station for the Salvation Army.”

The church’s governing body – known in the Presbyterian tradition as the Session – balked at first because they were concerned about COVID-19 transmission.

“This was back in the early days of the pandemic, when we thought the virus could live on walls for a long period of time,” Hudson explains.

But eventually, as they became more adept at managing the pandemic, church leaders agreed to open the gym to the community. Adamy describes it as the pivot the church needed.

Church members got to know other organizations reaching out into the community, addressing hunger, homelessness, mental illness, addiction. “We realized we could make a difference,” Adamy says. “If we’re going to have this facility, let’s put it to use.”

A few months later, the church started offering showers to the city’s unhoused population.

The work begins here

According to the 2020 census, there are some 64,000 Black West Virginians. Karen Williams is proud to be among them. “I love West Virginia,” she says. “I love it.”

But it’s not a complacent love. That would hardly do.

Williams was raised on the West Side, raised her own family here and has spent a lifetime serving it and her broader community, wherever, as needed.

She’s a career educator, from Head Start and elementary school to college courses. “I feel like I’ve taught half the city of Charleston,” she says.

She’s spearheaded campaigns for social justice and women’s rights. A particular area of focus over the years has been voter registration, urging her community to engage in the change they intend to see by going to the ballot box.

With the outbreak of COVID-19, Williams assumed yet another role. In the early days of the pandemic, she served as the Health Resources and Services Administration director for the Partnership of African American Churches. There, she oversaw a team of community health workers who serve the entire state.

The team’s initial task was to increase access to COVID-19 vaccinations in underserved communities, most particularly African American communities, which have suffered disproportionately from the virus – another example of how faith-based organizations have stepped in to fill the gaps.

More recently, the community health workers have taken on another task. With the expiration of the COVID-19 Medicaid and SNAP emergency allotments, they’re deployed to ensure that those who are eligible for Medicaid remain on the rolls.

“I’m getting dressed up on Saturday,” Williams says. She’ll be visiting the library to read to kids about Black history and to assist with Medicaid enrollment.

It’s all of a whole. The undergirding of everything the Partnership of African American Churches does is its dedication to addressing the health disparities among West Virginia’s underserved communities – and that work begins on the West Side.

African American adults are at greater risk than white adults for diabetes, hypertension, obesity, asthma and heart disease. Life expectancy among African Americans is four years lower than that of white Americans. Infants born to African American women are more than twice as likely to die as those born to white women.

Rev. James Patterson, PAAC’s founder and CEO, is driven to address those disparities.

On a warm, overcast fall afternoon, Patterson stands outside a 12,000-square-foot abandoned Sav-A-Lot on Virginia Street that PAAAC has purchased, with assistance from the City of Charleston, detailing his vision for the facility: primary care; behavioral health services; dentistry; services for children, both sick and well; a pharmacy.

As Patterson shares his plans, a Black man approaches, limping, most probably in his 60s, clearly on hard times. Rev. Patterson shakes his hand. The man has had difficulty getting treatment for a leg injury.

“This is why we need people of color doing this work,” says Mildred Tompkins, Patterson’s executive assistant. A conversation has been initiated between someone in need of help and someone who can provide it, potentially opening the door to a continuum of care.

The message, Tompkins affirms, is, “We’re out here. We’re in the community.”

Patterson emphasizes that PAAC’s health services are available to everyone in the community. But overcoming racial disparities is an urgent calling.

“We have these poor health outcomes,” he says. “Somebody, some organization, some institution, has to address that.” People in this community, and those throughout the state likewise marginalized, are falling through the cracks.

The social determinants of health – where we live, work and worship; the quality of our education system; access to well-paying jobs and other economic opportunities – are primary contributors to those disparities, Patterson says, as is “not understanding the whole culture and how to go about providing services in a Black culture. So we’re trying to do that.”

He says he’s sometimes accused of “‘trying to start a segregated health center.’ And I say, ‘No, no, no. I’m trying to integrate the segregated system that already exists.’”

PAAC received a license to provide behavioral health care in 2019 and continues to expand those services. Its services for addiction include medications for substance use disorder and recovery housing. And its Infinite Pathways Men’s Treatment and Recovery Facility provides 24/7 peer recovery coaching and housing.

“We will support whatever path, whatever keeps you [in recovery],” Patterson says, “whatever gives you the ability to function and take care of your responsibilities.”

African American adults are more likely than white adults to report persistent symptoms of emotional distress but are less likely to receive appropriate treatment. Distrust for medical institutions runs deep in Black communities, with the most widely cited source being the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, in which 600 Black men were monitored but not treated for syphilis. African American patients are also more likely to be misdiagnosed than white patients.

Mental Health America attests that Black health care providers are more likely to offer “more appropriate and effective care” to Black patients.

“There just needs to be somebody of color doing this work,” Patterson says, someone with “the cultural context from which to provide the care.”

“Somebody has to improve these health outcomes. Somebody has to do that work.”

This story is part of a four part series The West Side: A Community Defining Its Future. Explore the entire series here.

Laura Harbert Allen is a Report for America corps member covering religion for 100 Days in Appalachia and Taylor Sisk is 100 Days’ health correspondent. Support their work here.