Depending on who you ask, the development of the Elk City district on the West Side of Charleston, West Virginia, is either “gentrification” or “revitalization” – though some will say both.

Karen Williams, a lifelong Charleston resident who grew up on the West Side, says the transition from homes and businesses in decline to upscale renovation puts you “in a different world.”

Elk City is a two-block business district along West Washington Street in Charleston. Over the past seven years, about a dozen businesses have moved into renovated storefronts that had been largely empty for more than a decade. The businesses in the Elk City district are mostly white owned and operated, while the neighborhood around it has the most Black residents in the city.

“I think it’s a good thing that we’re seeing a revitalization on the West Side of businesses,” says Derek Hudson, who oversees outreach services at the neighborhood’s Bream Memorial Presbyterian Church. “I think it’s a bad thing that there’s not more minority-owned businesses though. And I think that it should be a more focused attempt at bringing them in.”

Williams is concerned that a relatively small sector of the West Side has received the lion’s share of public and private financial investment. One example is a 2022 lighting-infrastructure initiative, called the West Side Gateway Lighting Project, in which $483,000 was spent to upgrade street lighting in the Elk City district.

“There was money allocated to a certain portion of the business districts,” Williams says, “but it did not go into the residential district.”

Elk City, Williams says, was not designed with the Black community in mind. “I’ve never seen anyone that I know actually go into the shops over there.”

Williams says development efforts on the West Side reflect a troubling pattern of discrimination toward African Americans in the neighborhood. Redlining shut Black West Side residents out of the financial system for a century. And the construction of the interstate in 1974 displaced thousands of Black Charlestonians.

Williams – along with other leaders and activists on the West Side – is concerned the Elk City development is leaving Black residents out again.

But not everyone sees it that way.

Michael Ferrell was elected to his first term on the Charleston City Council in November 2022. He was raised on Vine Street, in the West Side neighborhood known as the Flats. He and his wife now live in his childhood home.

“Nobody was pushed to the side. I think that’s a misnomer,“ Ferrell says. “All they did was try to spur business and spruce up the place.”

‘A real community vibe’

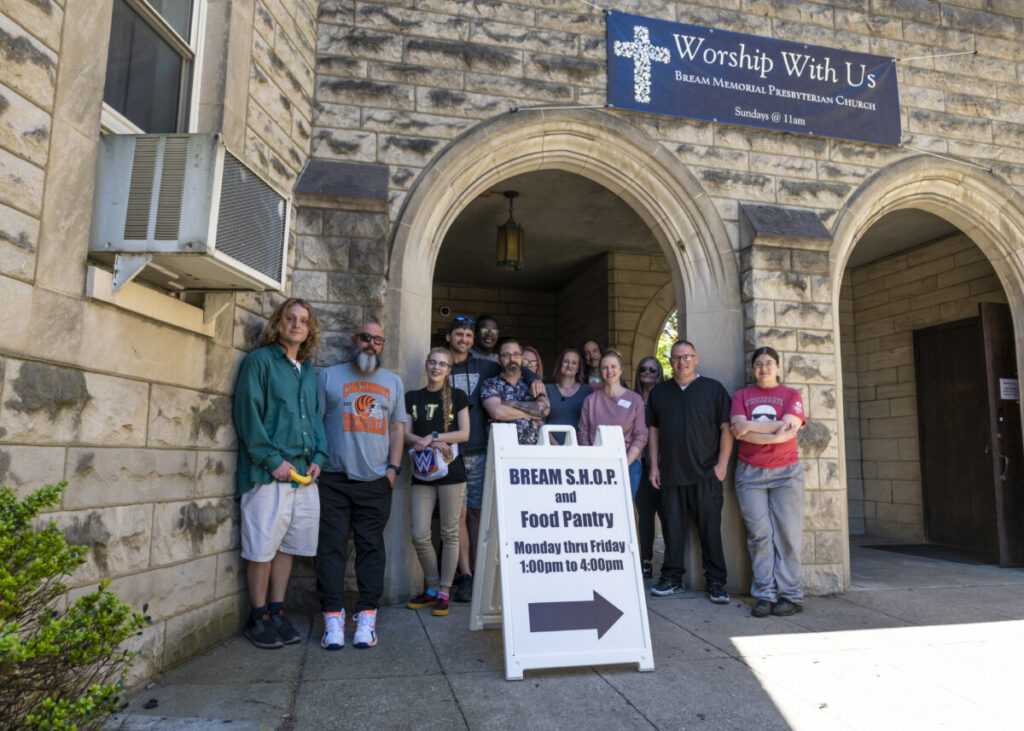

Bream Memorial’s gray stone tower juts into the sky, a landmark that defines the western edge of the Elk City business district.

The church operates the SHOP – Showers, Health Care and Outreach Program – which provides critical supplies and services to anyone in need. The SHOP is the only drop-in center for unhoused individuals in Charleston and has the only free public laundry facility on the West Side – and the washers and dryers run nonstop. Other services include a grocery program for housed and unhoused residents and peer-support counseling for individuals struggling with substance use disorder. Domestic violence counselors are also available.

Bream’s pastor, the Rev. Dawn Adamy, grew up in Roanoke, Virginia, but had spent the past three decades in New Jersey. She arrived in Charleston just months before the outbreak of COVID-19. Her immediate impression was of a congregation that was “doing what God called them to do” in their community. She felt at home.

The church’s outreach efforts include a courtyard where drop-in clients can sit when the weather is nice. And Hudson fires up the grill on sunny days, preparing hot dogs and hamburgers for anyone who stops by. But the courtyard also borders West Washington Street in the Elk City district, and the church has received pushback for allowing unhoused individuals to congregate so close to local businesses.

But some business owners are more sanguine with the church’s outreach work than others. Among those is Hilary Harrison, co-founder of Kin Ship Goods, an apparel and home goods boutique that shares an alley with the church.

Harrison grew up in the 1990s in Sissonville, West Virginia, a small town about 14 miles northwest of the West Side. For her at the time, coming to Charleston meant coming to the business district on West Washington Street, where stores like Pile Hardware and the Charleston Department Store provided plenty of choices for shoppers.

“I had a lot of good memories associated with it,” Harrison says of the West Side.

When she and her partner began scouting locations for Kin Ship Goods about a decade ago, they first looked at the West Side, but couldn’t find a space that worked, and settled on a spot downtown. After a couple of years there, the landlord decided to raise their rent; they once again looked to the West Side, and this time were successful.

Harrison is happy to be here. “Everyone knows each other and there’s a lot of history and character over here,” she says. “It just has a real community vibe that I like.” She and her partner also live on the West Side.

Harrison believes the problem is more one of perception than reality. “It’s just been years and years of hearing how dangerous and awful it is.” She believes the West Side should be viewed with fresh eyes.

Harrison says she and her staff have a great relationship with Derek Hudson and all the folks at Bream. “I think the work they’re doing is really important.” They’re making a difference, she says. “And they’ve been wonderful neighbors. Anything we ever need, they’re there.”

She and several other business owners in the immediate vicinity are on a text chain with the Bream outreach staff. “For example, if someone gets in the dumpster out back and leaves trash everywhere, we’ll all chip in and give some money to Derek to pay one of his workers to help clean it up.”

“We’re all trying to work together to address any issues.” Those that have arisen, she says, have been minimal.

“We’re happy to talk to anybody who wants to have a constructive conversation about how we can address some of the issues,” Adamy says. “And I’m happy to say those conversations have gone well.”

‘Merciful chaos’

Joe Solomon, a member of Charleston’s city council, sees what’s unfolding on the West Side as very much a “West Virginia story,” a nuanced one, with a lot of push and pull – the story of a community attempting to reconcile sometimes divergent views of its future – whereby tensions arise, and sometimes, hopefully, for the better.

“[Bream] said we want to expand and take care of more people and offer more wraparound services,” and it created “this fissure, where people who wanted to lift up Elk City and the West Side in a very inclusive way came to the defense of that program, while others, Solomon says, were perhaps taking “more of a gentrifying approach” and “leading the charge to end Bream’s expansion efforts.”

But, he points out, one of those businesses that was leading this charge was among the first in the city to carry naloxone. It’s not always cut and dried. “I feel like there are these fissure moments where it gets really hot,” Solomon says, then out of that often comes some sense of common direction.

“When I think of Charleston’s West Side, I think of a place that’s always healing and always willing to do the work,” he says, “and I think of a place that’s been hurt a great deal by local and state politics and policies.” That hurt, he says, “didn’t start with the Triangle District displacement, but that came with a whole lot of ripples.”

“And I think the litmus test for Charleston is how we work together to help repair and rebuild and renew the West Side.”

There’s a balancing act happening on the West Side: How to revitalize this historic neighborhood while considering the interests and needs of everyone, including those who have been or are currently living on the margins. Economic growth in the neighborhood has always come at great cost to the Black community, a painful history that’s reflected today in the mostly white-owned businesses of the Elk City district.

Solomon believes that, most likely, a lot of “merciful chaos” lies ahead for the West Side. There certainly is no single solution. Not everything will work. “You’re going to have to invest in a whole array of projects and people, and over a long time.”

But who decides on what projects to fund and who should lead them is an ongoing debate.

This story is part of a four-part series The West Side: A Community Defining Its Future. Explore the entire series here.

Laura Harbert Allen is a Report for America corps member covering religion for 100 Days in Appalachia and Taylor Sisk is 100 Days’ health correspondent. Support their work here.