This article was originally published by Ohio Valley ReSource.

Carol Davis has noticed the West drying up. Where she lives, in the Four Corners area of New Mexico and on the Navajo Nation, years of drought have left former oases dusty and dry. Though the drought has some roots in wider climate issues, Carol says much of the groundwater in her area has dried up because nearby coal mines and power plants were using immense quantities of water for many years.

“We were selling our water to Navajo Generating Station and the Mojave Generating Station,” she said. “They were paying nothing to use our water. Meanwhile our water table is depleted, our seeps and springs are drying out.”

Across the continent — in Letcher County, Kentucky — Elaine Tanner also has complaints about how the coal industry has affected her community’s watershed. Though the Appalachian highlands and Ohio Valley are water-rich, mining has disrupted mountain hydrology, increasing flood risk, which has only been compounded by the climate-change trends of more intense rainstorms.

Tanner, who is of Shawnee and Cherokee descent, says she feels a kinship with communities like Davis’s. “That’s the thing we have in common,” Tanner said. “It’s the water.”

On a blue-skied December day, Tanner rode her ATV up the mountainside to survey damage from the previous week’s heavy rains. Like much of central Appalachia, the surrounding land was once mined for coal — in this case Deane Mining. When the company pulled out in the early 2000s, Tanner said, they left behind a mess. Ponds meant to catch water from the changed landscape have been ineffective. Instead, water pours down the mountain, pushing mud toward her house. She’s now making plans to relocate her home up the hill to a spot less threatened by flooding and mudslides.

Similarity and Solidarity

Destabilized watersheds are just one of many issues that both coalfield regions are grappling with. Pollution and public health are also a shared issue — coal industry byproducts have left toxic metals in the air and water in both Appalachia and the Navajo Nation, contributing to high excess deaths from cancer, lung disease and heart disease in rural communities with limited access to timely healthcare.

Many of the similarities fit into a pattern that can be seen across the globe — what economists call the “resource curse”. Places rich in natural resources often develop an extraction economy dominated by outside powers who extract both resources and profits. As on the Navajo Nation and across central Appalachia — communities get left with damaged lands, an undiversified economy and little local control.

“From the beginning,” Tanner said, “these are indigenous lands. Colonialism walked in and took them away, and chased the natives out.”

During the Bush administration, both “war on coal” rhetoric and anti-strip-mining activism were at their peak. Concerned community members in both places traveled to support one another’s efforts, and to grow the conversation about how to handle the coal industry’s presence, and its departure. The ongoing conversation has led to a framework for what advocacy groups want to see for the future of coalfield areas.

Organizing for a Just Transition

Tanner’s organization, Friends for Environmental Justice, is one of many groups calling for a “just transition” away from the coal industry. The idea is that redevelopment projects should benefit local communities and ecosystems rather than corporations and outside investors.

Carol Davis works as the director of Diné Citizens Against Ruining Our Environment, or Diné-CARE. The organization works across the ancestral lands of the Navajo (or Diné) and Hopi peoples, an area full of high plateaus as well as deserts and meadows that have long been mined for coal, uranium and other minerals.

“That’s actually the reason why our government was even established,” Davis said. “The federal government wanted to work with energy companies. They wanted to streamline a process to lease reservation lands for their use for over long periods of time.”

Like Tanner in Kentucky, Davis and Diné CARE advocate for a just transition — meaning environmental protection and economic diversification in ways that benefit and empower local communities.

These organizations and their allies recommend tighter regulation on active coal companies, and also advocate new types of diversified, sustainable, and non-exploitative economic development. Focuses include supporting traditional arts and agriculture, renewable energy development, also investing in mine reclamation to create jobs while also benefiting local communities by restoring ecosystems and protecting residents from coal-related water and air contamination.

Coal Closures and Job Losses

After years of competition from wind and solar, the Navajo Generating Station— a major coal-fired power plant at the edge of the Navajo Nation — was shut down in 2019, along with the enormous Kayenta and Black Mesa Mines that supplied its fuel.

Environmental activists applauded this shift, but many noticed increased friction in their communities as a result of coal closures. Both Davis and Tanner can recall tension between environmental activists and coal industry workers, particularly at public hearings around mine and plant closures. People worried about losing their jobs would show up en masse at the behest of the company, who would make it “kind of like a party” for the workers, Davis said.

Davis wants to see the surrounding communities treated with respect as the shifting economy dictates changes to what jobs are available. In an area with an unemployment rate around 50 percent, Davis says, they need resources to ensure an equitable future. As in central Appalachia, much of the Navajo economy was based around working in coal mines and power plants, which, while dangerous, were well-paying jobs that have not been replaced.

“These are sacrifices that people made for almost half a decade in the coal-impacted communities,” Davis said, “just so that the rest of Arizona, Nevada and California could live a good quality of life with electricity.”

The Navajo Nation also received up to $50 million in mining royalties each year – revenue it depended on, much as Appalachian communities once depended on the billions of dollars in severance tax revenue generated by the same industry.

Planning for the Future

Community organizations across the mesas and mountains are grappling with the transition happening as coal employment continues to decline.

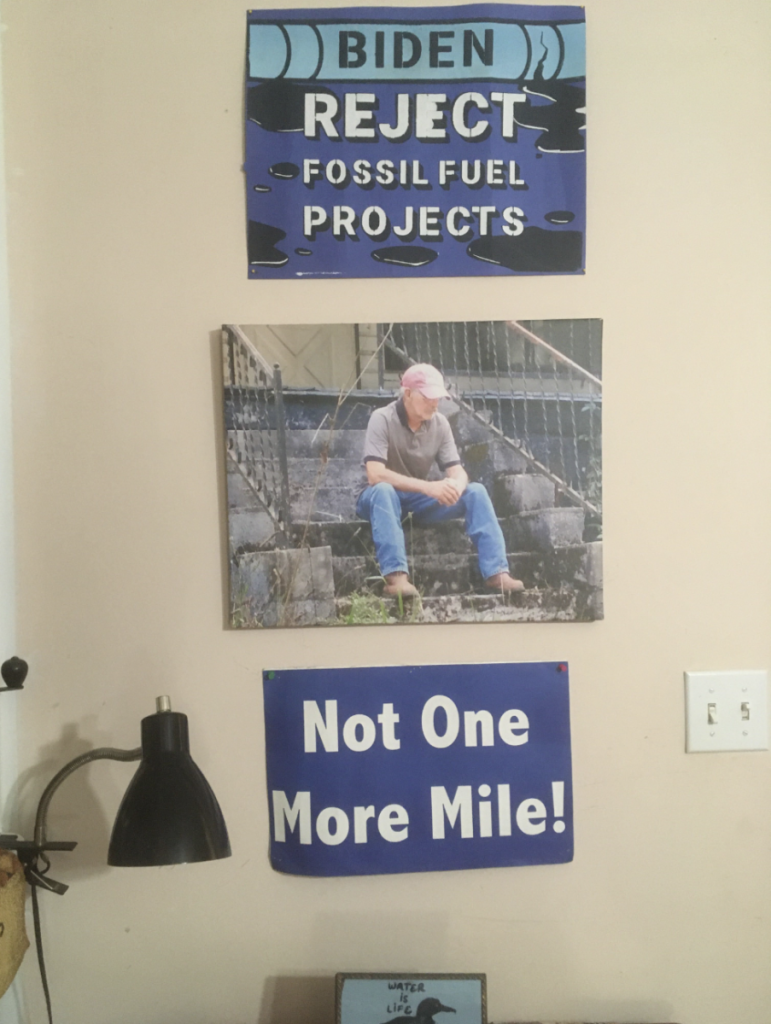

Tanner went to Washington, DC in October with indigenous activists from all over the country to demand that Joe Biden fund energy transition and hold fossil fuel companies accountable — an increasingly unified call from indigenous activists all over the country who are feeling the impacts of extractive industry and climate change.

“When we voted for him, we expected more,” Tanner said. “I think that would be an easy way to put it.”

Davis, too, believes it’s the responsibility of the powerful to hold utility and coal companies accountable for cleanup as they wind-down their operations. “They need to reinvest to help ensure that those communities will thrive in the future,” Davis says.

Changes are in the works. The Navajo Nation is moving forward with new solar projects, each expected to produce hundreds of megawatts of energy for large utilities in the Southwest, and also deliver millions in tax revenue to the tribe. In the Kentucky mountains, the federal Abandoned Mine Lands Fund is supporting new mine reclamation and economic development projects.

Still, Tanner and Davis say that old power structures are still in place, and there’s much work to be done to hold them to account.

In a video from the October protest, Tanner steps up to the podium to speak to the assembled crowd about her mountain, and to assert her solidarity with all those listening across Appalachia the Southwest, and the rest of Turtle Island — as some indigenous peoples call North America, affirming that the continent is rightfully Native land, much of which remains unceded.

“You’re not alone,” she tells the crowd. “We’re in this together, and we’re here for the duration.”