This article was originally published by Ohio Valley ReSource.

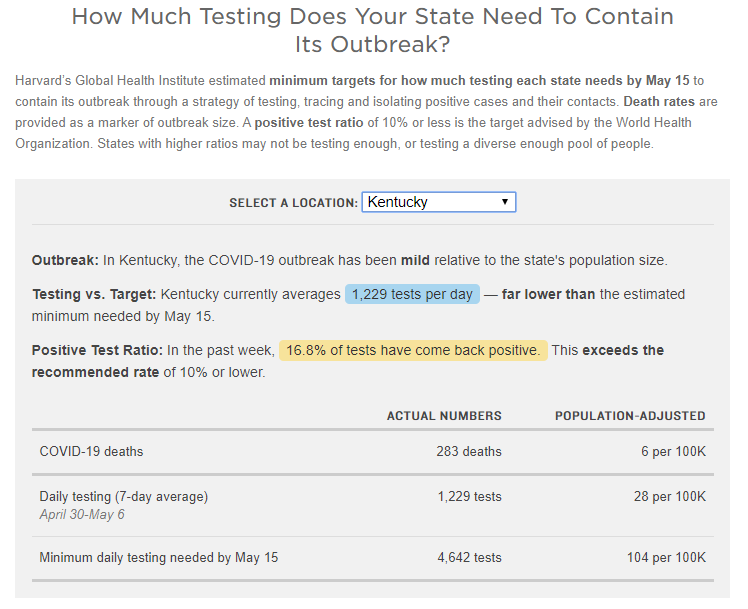

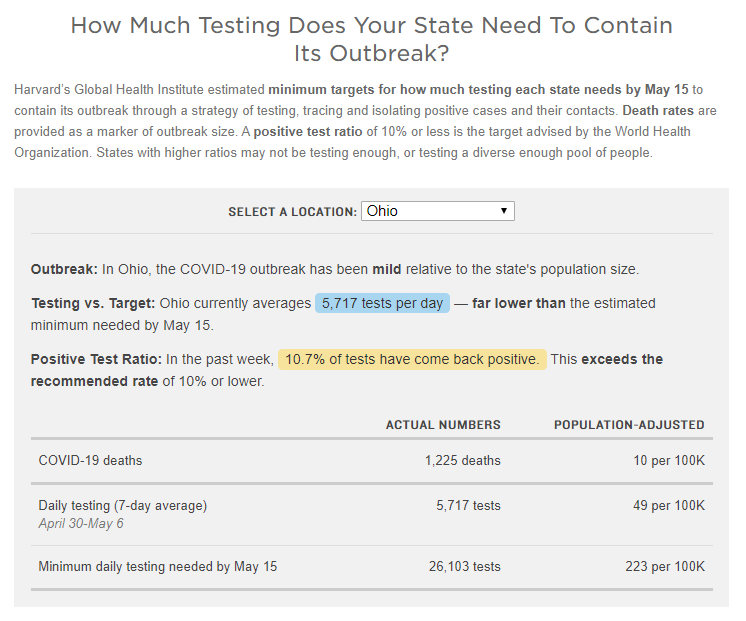

An analysis by Harvard scientists and NPR finds that most states — including Kentucky and Ohio — are not testing enough residents for coronavirus in order to meet recommended benchmarks to safely begin to reopen their economies.

That analysis by Harvard’s Global Health Institute found that West Virginia is roughly meeting the minimum targets for coronavirus testing, while Kentucky and Ohio lag behind the recommended testing levels. Data on Kentucky and Ohio also show other indications that more testing is needed.

For example, the Harvard/NPR analysis of a week’s worth of Kentucky’s testing found that Kentucky averaged 1,229 tests per day — far lower than the estimated minimum needed by May 15 in order to begin to safely relax some of the business closures and social distancing safeguards in place.

The Harvard scientists also recommend that the ratio of coronavirus tests that return a positive result be 10% or lower, a threshold the World Health Organization also recommends. For the testing done during the week of April 29 through May 5, the ratio of positive tests in Kentucky was nearly 17%, far exceeding the recommended limit.

Similarly, Ohio averaged 5,717 tests per day, again far lower than the minimum the Harvard team estimated would be required by May 15.

However, both those states are ramping up testing capacity rapidly as they approach a phased-in reopening of some businesses and services. An analysis by member station WFPL of more recent testing data from Kentucky shows a far lower ratio of positive results, an indicator that the state is making progress.

Dr. Tom Tsai is an assistant professor at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health and the Global Health Institute. He’s also a surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

In an interview with the ReSource’s Becca Schimmel, Tsai explained some of the public health benchmarks for safely reopening state economies, and talked about how an increase in testing and contact tracing can help overcome some of the challenges of resuming work life during the pandemic.

***

Dr. Tom Tsai: The thresholds we look at in terms of whether a state is ready to reopen are several-fold. One is to make sure their test positive rate is below 10%. That’s a useful premise, because we know that in South Korea, their test positive rate was 2 to 3%, Germany was 6 to 8%. And anything above 10% suggests that you’re under-testing the population. So the test positive rate is a helpful metric to consider.

The second is the number of tests that you’re doing as a per capita basis for the country. And that’s largely driven through a complex relation of issues, but including the burden of cases in your state, but also the strategy of why you’re testing. Then the most important thing is whether the actual number of cases is decreasing with time and the number of hospitalizations is decreasing with time.

Just looking quickly at some of the numbers for Kentucky and Ohio, I think they’re, you know, in a position where they are past the peak of where the cases are, and are in a plateau stage and even starting to see some of the cases decline, which is good news.

The overall message, though, is more important than the thresholds for reopening, that this is not an on-off switch, but really a dial. And that the states need to really consider having very clear metrics on what success or failure looks like, and understanding that in the next weeks to months, based on the testing data, if the number of positive cases is actually increasing, then we may have to dial-up social distancing, again, in order to make sure that we’re not inadvertently creating a resurgence of cases by lifting social distancing too early.

Schimmel: Do you think that if social distancing policies end and then need to be put back in place, that people will want to follow those guidelines again after they’ve had them dialed back?

Dr. Tsai: There’s definitely a social distancing fatigue that we’re already seeing in lots of space, especially as the weather is getting nicer and people are more likely to leave their homes. That’s why it’s so crucial to get the policy right now, because in some ways, once the floodgates open, in terms of trying to return to normal, it’s gonna be very hard to reinstitute social distancing measures that have been placed over the last several weeks, to months.

Schimmel: What are the risks to the states if they open without meeting those benchmarks?

Dr. Tsai: Well, we’re in a lockdown now, nationally, because we didn’t have the right testing capacity over the last several months, and we want to make sure as we consider reopening that we can stay open. And that means having enough information on testing. But testing is only one piece of the puzzle. Moving forward will likely involve really thoughtful and aggressive contact tracing to make sure we’re testing everybody who’s been exposed to a contact. It also may mean that we need to do workplace surveillance.

Schimmel: Aren’t there concerns about violating HIPAA and personal privacy when taking employee temperatures that some have been implementing in workplaces?

Dr. Tsai: I think it’s important to frame it in the right way, that this isn’t meant to be an obtrusive way of monitoring. This is really to help people have the right and best information for their own safety. And, you know, we think about you know, when you’re driving a car, right, everybody wears a seatbelt. We follow the rules of the road, we follow traffic lights, we stop at stop signs. And those aren’t invasions of your autonomy or privacy, but that’s basically following the rules of the road and making sure that it’s safe for everybody on the road, safe for society. I think some of these strategies — wearing masks and public being screened for temperatures — can be viewed in the same way. They’re not affronts to your personal liberty. It’s making sure that everybody including yourself is safe from COVID-19.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.