This article was originally published by Ohio Valley ReSource.

The federal Mine Safety and Health Administration announced Wednesday it will collect information on how dust from silica, or quartz, has contributed to Appalachia’s worsening epidemic of black lung disease, and ways that mining operations might prevent exposure.

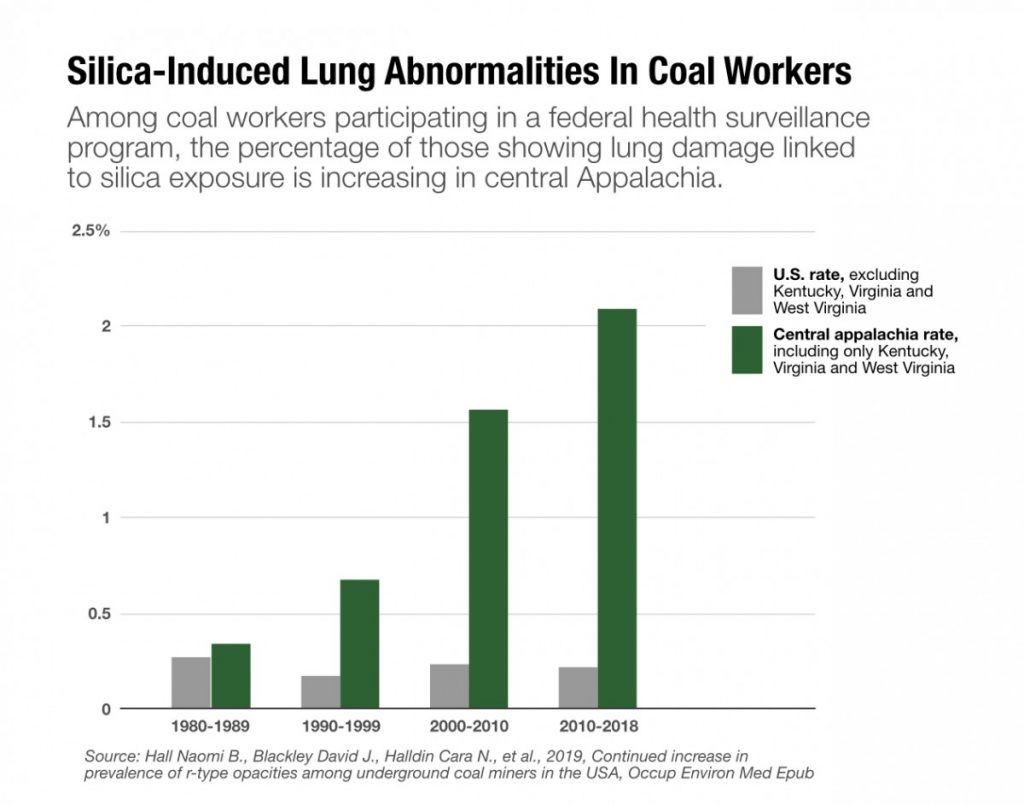

The announcement comes after an NPR investigation last year found that MSHA had failed to sufficiently regulate silica dust exposure, contributing to the increase in disease among coal miners. Silica dust comes from quartz found in rock layers near coal seams and can be far deadlier than coal dust alone. MSHA’s existing standards on coal dust can indirectly serve to limit miners’ exposures to quartz in respirable dust. But its standards are less stringent than those that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration applies to other kinds of workplace exposures.

The move marks a departure from MSHA’s previous stance, which was that a request for information on the effects of a 2014 coal dust rule would be sufficient. That rule further limited coal dust exposure and was hailed as an important and overdue move to protect miners, but it did not specifically address silica dust exposure.

In the request for information, which will be published Thursday, MSHA said it “recognizes the importance of controlling miners’ exposure to quartz and seeks information and data to determine if existing engineering and environmental controls can continuously protect miners.”

The request for information seeks input on economically and technically feasible solutions to silica exposure, including a lower silica dust standard and controls such as masks and respirators to help achieve compliance.

Miners exposed to quartz can develop lung diseases that are preventable, progressive and may lead to death. As many as one in five experienced coal miners in the Appalachian region has some form of black lung.

Coal miners are exposed to more quartz dust now than in the past because they are often mining thinner seams of coal and are using machinery that can produce more dust than was produced with older forms of mining.

“MSHA is aware that there may be conditions where existing engineering or environmental controls may not be adequate to continuously protect miners’ health in areas where there are high levels of quartz dust,” MSHA said in the request for information.

The mining industry has known since the 1970s that silica dust was harmful to miners’ health. But efforts to regulate the dust have stalled, largely due to pressure from industry groups.

“The Department of Labor is committed to having the information to make important decisions in order to best protect America’s miners,” said Acting Secretary of Labor Patrick Pizzella in a press release.

MSHA will accept comments for 60 days.