This article was originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource.

As a new plastics industry emerges in the Ohio Valley, a report by environmental groups warns that the expansion of plastics threatens the world’s ability to keep climate change at bay.

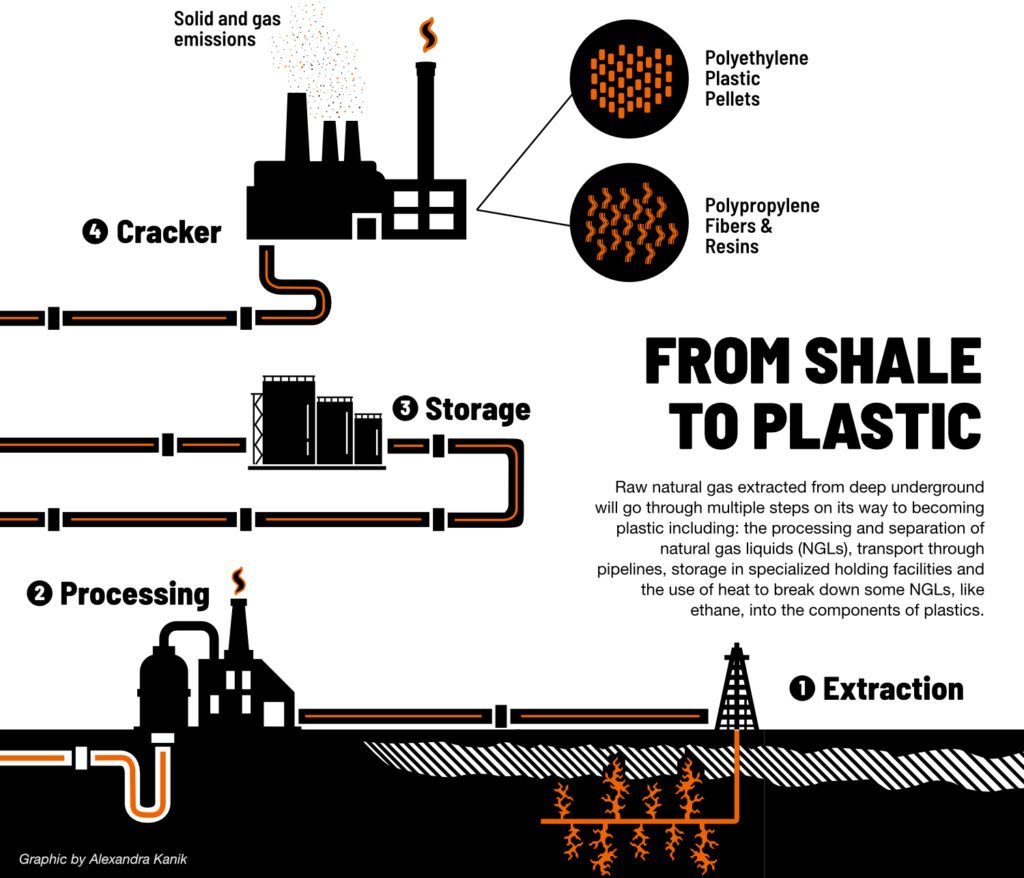

The report released Wednesday by the Center for International Environmental Law, Environmental Integrity Project, FracTracker Alliance, and others used publicly available emissions data and original research to measure greenhouse gas emissions throughout the entire life cycle of plastics. That includes the extraction of natural gas, used as a feedstock for plastic production, to the incineration of plastic products or their final resting place in the world’s oceans.

“Ninety-nine percent of what goes into plastics is fossil fuels and their climate impacts actually start at the wellhead and the drill pad,” said Carroll Muffett, president of the nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law and one of the authors of the report. “In light of the fact that the build-out of plastics infrastructure is ongoing and accelerating, we wanted to better understand the implications of that massive new build out of plastics infrastructure for the global climate.”

Fossil-Fueled Plastics

The report estimates production and incineration of plastic this year will add more than 850 million metric tons of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, or equal to the pollution of building 189 new coal-fired power plants.

That figure will rise substantially over the next few decades as the demand for single-use plastic continues to grow, the report finds. By 2050, emissions from the entire plastics life cycle could account for as much as 14 percent of the earth’s entire remaining carbon budget.

Plastics manufacturers are investing millions into new petrochemical plants, including in the Ohio Valley, driven by demand and cheap natural gas from the fracking boom.

For example, the report cites Shell’s Monaca ethane cracker plant currently under construction in Beaver County, Pennsylvania. It’s permitted to release up to 2.25 million tons of greenhouse gas pollution annually. Similarly, Thailand-based PTT Global Chemical is seeking permits for a cracker plant in Belmont County, Ohio, across the Ohio River from West Virginia.

The plant would be permitted to release the equivalent carbon dioxide emissions of putting about 365,000 cars on the road. Muffett said that sort of increased investment in plastics manufacturing was one of the main reasons the groups decided to highlight the climate implications associated with plastics.

“This petrochemical build-out is a key driver of plastics contribution to climate impacts now and in the future,” he said. “This build-out is going to lead to the production of massive quantities of new plastics. It’s also going to lead to the incineration and disposal of massive amounts of new plastics.”

Industry Response

In a statement, the trade group the American Chemistry Council said the report missed the mark because it failed to take into account that plastics are increasingly replacing heavier, more energy-intensive materials, which can reduce emissions during both the manufacturing process and during transportation.

“Because plastics are strong and lightweight, they help us do more with less,” stated Steve Russell, vice president of the group’s plastics division. “Plastics help us ship more product with less packaging, which means fewer trucks on the road; plastics help make our vehicles lighter and more fuel efficient, so we go further on a gallon of gas; and plastic insulation and sealants help make our homes and buildings significantly more energy efficient by sealing off outdoor temperatures.”

The report also outlined a gap in emissions data for the plastics life cycle, particularly in its infancy, when natural gas is being extracted and transported to refineries and other manufacturing facilities.

“Throughout that process, there are significant emissions, and many of them remain unquantified,” Muffett said. “Even many of the sources of emissions, like compressor stations, or the miles of pipelines involved, official estimates of how many compressor stations there are can vary by an order of magnitude, and that means that there are really fundamental senses in which the data for understanding the scale of this problem just isn’t there. And it needs to be there.”

The report also called for additional research into the impacts of microplastic pollution in the world’s oceans, including more study of the ways in which microplastics may be negatively impacting the ability of oceans to take up carbon emissions.