It took a few weeks for Hannan High School principal Karen Oldham to realize her school might have made history. She was so busy with the day-to-day grind of running the small, rural Mason County school that it didn’t cross her mind, until an elderly alumnus brought it to her attention.

Oldham still was not completely certain the school had done anything significant, so before making any kind of formal announcement, she phoned the West Virginia Secondary Schools Athletics Commission and asked officials there to do some digging. They called back a few days later.

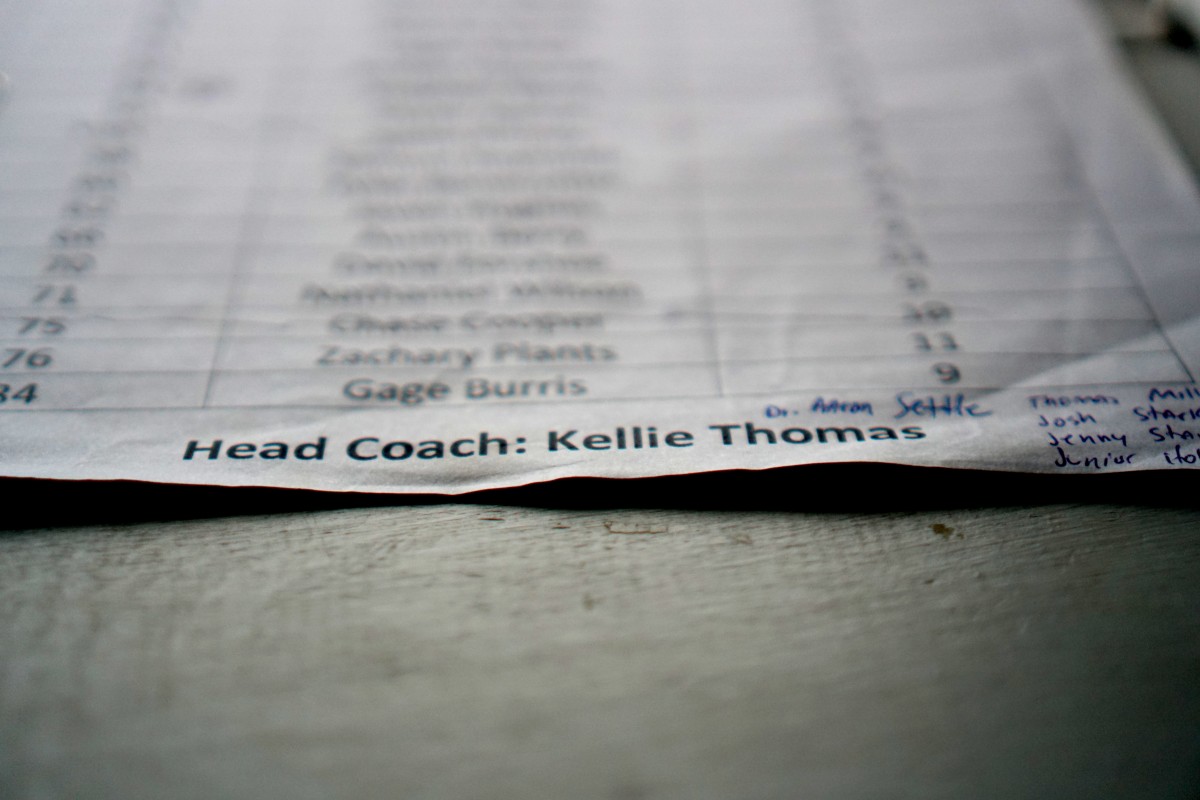

It was true: Hannan had hired the first female head football coach in West Virginia history.

The Point Pleasant Register got the scoop. Then, Huntington’s Herald Dispatch and local television stations picked up the story, which led to national coverage in USA Today.

It was all a shock for Oldham. It seems that no one—not Oldham, not the hiring committee she put together, not the superintendent who added the hire to the school board’s agenda, nor the board members who unanimously approved it—realized they were doing anything newsworthy.

“Never did her gender come into our minds,” Oldham says.

All everyone knew was, they had found the best person for the job. And that person was Kellie Thomas.

* * *

The voice of Axel Rose singing “Welcome to the Jungle” cuts through the sour air of the Hannan Wildcats’ locker room as players lace up their cleats and tug navy blue jerseys over their shoulder pads.

In her office, Kellie Thomas is wearing her own uniform: a ballcap with a turquoise H, a Hannan polo shirt with a long sleeve shirt underneath, khaki cargo shorts with a Washington Redskins lanyard hanging from the left pocket and leather Carhartt boots with pink wool socks climbing her bare calves. She pulls on a hooded jacket to protect herself from the night’s drizzling rain and begins going through her pre-game preparations.

She replaces the batteries in the headsets she and her two assistant coaches will use to communicate during the night. She pumps up the three footballs that, as the home team, Hannan is required to supply for the game. Then she calls defensive back and running back Isaac Colecchia into her office.

Colecchia isn’t wearing pads. He suffered a concussion in last week’s game and is sitting out this week. Together, he and Thomas go through a checklist of symptoms—headache, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, insomnia, anxiousness, depression, and a few dozen more—that Colecchia ranks on a scale of zero to six. He gives most symptoms a zero, but ranks “sensitivity to light” and “sensitivity to noise” at one each. Once the symptoms go away and he’s cleared by his doctor, Colecchia will be eligible to play again.

The moment offers a glimpse at Thomas’s recent past. Although this is her first season as head football coach, she spent close to two decades as Hannan’s athletic trainer. She was there at every practice, scrimmage and game to tape up players’ ankles and wrists. Thomas was such a constant, stable presence that, over time, she became a confidant for players.

“She was their go-to when they had problems with previous coaches,” Oldham says.

That is why, when former Hannan coach Brian Scott resigned following the 2017 season, players approached Thomas and begged her to apply for the position.

With the questionnaire completed, Thomas dismisses Colecchia and leaves the office. She rallies her troops and leads the team out of the corrugated aluminum fieldhouse to a patch of grass just outside, where players arrange themselves into four rows and begin their warm ups.

The team normally warms up on the field, but tonight is homecoming. The field is currently occupied by members of the homecoming court and their parents, awaiting the announcement of this year’s king and queen.

As her players stretch and run drills, Thomas and defensive coordinator Thomas Miller size up tonight’s opponents, the Parkersburg Catholic Crusaders. The team isn’t much bigger than Hannan but the Crusaders are coming into this late October contest with a 7–1 record. Hannan hasn’t won a game all season.

When homecoming festivities are finally completed, the team moves its warm-ups onto the field. Then it’s the national anthem, handshakes between team captains and the coin flip.

Hannan wins the flip and elects to receive. Parkersburg punts and stops the return at Hannan’s 25 yard line. Then, in the first drive of the game, Hannan quarterback Matthew Qualls takes the snap, hops back on his right leg to pass and launches the ball into the air.

Immediately, a Crusader linebacker reaches up and swats the ball back to Earth.

“Oh, crap,” Thomas says.

* * *

Football is a difficult sport for small schools like Hannan. The game technically requires 11 players on each side, but coaches prefer to have enough players to field two separate squads for offense and defense, plus a roster of second-string players to serve as backups. That’s why NFL teams have 53 players. Colleges often keep more than 100 on their active rosters.

Those kinds of numbers are not possible at a school like Hannan. The school has about 300 students in all, but that includes seventh and eighth graders. Only students in ninth through 12th grades are eligible to play high school football, and Hannan has around 180 students in those grades.

As a result, there are just 19 players on Hannan’s football team, which means most of those players spend nearly the entire game on the field, playing both offense and defense. There’s little opportunity for anyone to rest and recover on the sidelines, and it only takes a few injuries to jeopardize a game. In seasons past, the school has had to forfeit multiple games because there weren’t enough healthy players to field a team.

Their small size even hinders Hannan’s ability to practice. Most coaches practice plays by pitting their offense and defense squads against one another. Thomas has to split her meager roster into seven-player squads and run plays that way—players just have to imagine how the plays will work as part of an 11-player team.

All of this adds up to a team that, frankly, hasn’t been very successful.

“We don’t have a lot of wins. And that gets morale down,” Oldham says. That is why, in the 11 years Oldham has been principal at Hannan, she has had five head football coaches, including Thomas. Each of the previous lasted a few seasons, but, faced with bleak prospects and tempted by greener fields elsewhere, left the team behind.

Thomas, who has also coached girls basketball, volleyball, and track at the school, knew all of this when she applied to become head coach. But she also has a plan to overcome the challenges Hannan faces. She explained this strategy to the hiring panel that Oldham assembled to conduct candidate interviews. It’s one of the things that got her the job.

The cornerstone of Thomas’s strategy is conditioning. “My philosophy has always been, if you can’t keep up with a team, you have no chance of beating them,” she says.

That means players have to put up with grueling practices, with lots of running and upper body and leg work—the kinds of exercises some coaches use as punishment. Players have even been doing yoga with Mrs. Solomon, the school’s art and dance teacher, to improve their balance.

So far, this training has not translated into wins. But both Thomas and her players are seeing the effects.

“They say, ‘Kellie, we’ve never felt this good after a game before,’” Thomas says. “The scoreboard doesn’t show heart and determination. My kids have got both.”

Thomas is taking the long view. About half of her team are freshmen and sophomores. By the time those boys are juniors and seniors, Thomas hopes to have created a team of strong, well-conditioned and well-trained football players that can hold its own against anyone in the state’s single-A conference.

By then, she hopes, that heart and determination might start showing up on the scoreboard.

* * *

Fans haven’t always been understanding of Hannan’s lack of success.

“I don’t want to say ‘hate mail,’ but I’ll say I’ve got ‘inconsiderate mail’ about my coaches,” Oldham says, but so far, she hasn’t heard anything negative about Thomas. Not when the news broke that Hannan had hired a female football coach, nor after the season began and it was clear success still would not come easy for the team.

Shawn Coleman, a state trooper and parent who videos Hanna’s home games, hasn’t heard anything negative, either. “Being in the press box, you can hear the bleachers. I’ve not heard one person say anything negative about the coaching this year. I haven’t heard anybody talking bad about her.”

Thomas says she hasn’t experienced any blowback, either, but she knows her gender does not go unnoticed on the field. “As a woman, across from the opposing coach, I know that’s what they’re thinking. I know they’re thinking ‘Good lord, I hope they don’t beat us.’”

That doesn’t bother her, though. “To me, football is football, whether its a man or woman coaching. If you know the game, you know the game.” And this isn’t the first time she’s been the only woman on the field.

Thomas grew up idolizing her three older brothers. They all played football and basketball, so she did, too.

“Anything they did, I wanted to do,” Thomas says.

When she was in third grade, Thomas joined her elementary school’s girls basketball team. Not long after that, her brother Shawn, five years her senior, got sick and couldn’t play on his own basketball team. The school asked Thomas to take his place. She joined without hesitation because, “Anything a boy could do, I knew I could do just as well, or better,” she says.

In the summer, instead of joining a softball team, Thomas played on her uncle’s Little League team. She proved to be one of his best players, especially on the pitchers’ mound. Her peers were not always enthusiastic about her success.

“I didn’t have many guy friends,” she laughs. “You’d strike them out and they never would speak to you.”

Thomas played on Point Pleasant High School’s girls basketball team, earning all-conference nods each year, and threw discus and shot put on the school’s track team. She was the state shot put champion in 1989, her senior year, even after suffering a separated shoulder during basketball season. That same year she set a school shot put record, 38.10 meters, that stood for 27 years. She became the first woman inducted into Point Pleasant High’s athletics hall of fame.

After high school, Thomas attended Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia, where she walked on to the school’s track team. She majored in physical education and sports medicine, because she saw it as a way to make sports a more permanent part of her life.

“When I’m too old to play, I could still be around it. I knew I wanted to work with younger kids and teach them,” she says.

As a sports medicine major, Thomas also found herself spending considerable time with Marshall’s football team. She was on the Thundering Herd’s sidelines when the team defeated Youngstown State to clinch the school’s first national championship in 1992.

When players got their championship rings, the university gave Thomas and the other female trainers big square pendants featuring the same design. “It was an experience of a lifetime,” she says.

* * *

By halftime, the Crusaders have run up the score to 0–35.

As Mrs. Solomon’s dance squad takes the muddy field to perform a choreographed routine to Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” the Wildcats retreat to their fieldhouse to regroup. Offensive coordinator Josh Starkey scribbles on the whiteboard, trying to help players spot the holes in Parkersburg’s defensive line. “Little mistakes are killing us,” he says.

Thomas doesn’t make any speeches. Instead, she moves through the room, reading her players. Tight end and linebacker Dylan Starkey is sitting along the back wall, distressing over the likely outcome of the game. Thomas puts her fingers to her lips. “Dylan, shhh.”

She spots her quarterback Matthew Qualls sitting on a bench, elbows on his knees and his head bowed to the ground.

“I’ve got two quarters left to play in my last ever home game,” Qualls says, evenly. He’s a senior, and this is Hannan’s last home game of the season. They will finish the year on the road, an hour and a half away at Tolsia High School in Wayne County, West Virginia.

“Well, let’s make a statement,” Thomas says. “I just need you out of your own head. You’re afraid of falling, but you need to roll and get that throw out.”

Qualls nods his head. Halftime is almost over. He puts his helmet back on his head and starts for the door. “Last two quarters of my last home game,” he says.

* * *

Thomas knows it isn’t all about winning. Her players realize that, too.

“Kellie’s got a quote: ‘Student, then athlete,’” says sophomore safety Ryan Hall. “She wants us to succeed in learning and make sure we have good grades. And make sure we aren’t in trouble.”

This philosophy is something she learned from Jim Donnan, the coach who led Marshall’s football team to that 1992 championship. “It was no nonsense,” she says of Donnan’s coaching style.

“If you were penalized, he stuck to it. You violated the rules, you paid the consequences,” she says.

There is no better example of this than the aforementioned championship game against Youngstown State. Just before that game, Marshall’s starting kicker David Merrick violated team rules. Donnan, true to his word, suspended the player which meant the team’s backup—David’s older brother Willy, a soccer player who had never kicked in a collegiate football game—would take the field in the Thundering Herd’s most important game in years.

Willy Merrick ended up winning that game with a last second, tie-breaking field goal. But the tale could have easily had a less-than-storybook ending, and Donnan would have no doubt faced criticism for suspending his starting kicker at such a crucial moment.

The coach’s willingness to stick by his standards, no matter the consequences, stayed with Thomas.

“That’s how I run my program,” Thomas says. “I have a ‘two-strike, you’re out’ rule.” If one of her players gets detention or lets his grades slip, Thomas suspends him for a game. “The second time it happens, you turn your stuff in. They knew that when I took this position.”

Of course, none of this is to say that Thomas does not care about winning. If her team is following the rules—if everyone is keeping up with their school work, staying out of trouble, and staying healthy—she would like nothing more than to create a dominate football program at Hannan.

That competitive drive is on display every Friday, no matter who Hannan is playing or what the scoreboard reads.

In the first game of the 2018 season, Hannan played Tug Valley High School, the No. 5-ranked team in their conference. A referee approached Thomas before the game and asked if she wanted to shorten the second half. In West Virginia high school football, if a blowout seems imminent, the losing coach has the option of shortening the last two 12-minute quarters to six or even three minutes each. It’s a way of preventing scores from getting too embarrassing.

Thomas is morally opposed to the idea. “I’m competitive. I will fight, tooth and nail, to the last wire,” she says. She told the referee she would not, under any circumstances, shorten the game. “He said ‘I’ll ask you at half time.’”

By halftime, Hannan was losing 0–48. Both the referee and Tug Valley’s game administrator asked if she wanted to shorten the game.

“I said, ‘Absolutely not.’”

Thomas sees shortening quarters as an insult to her players. “That means I’ve given up on them. They take that to heart. I’m not going to do that to them.”

It goes back to a promise she made to the team when she agreed to apply for the head coach position. “My words to them were, ‘I will never quit coaching on you, during a game or during a season,’” she says. “I told them I expect the same from them. Not to quit on the field.”

* * *

Thomas does not ask for shortened quarters in the second half of the October game against Parkersburg Catholic either, even as Crusaders widen the score to 0–43 in the second half.

The stadium is quieter than in the first half. Much of the rain-soaked crowd has gone home. The announcer, seated up in the warm press box, offers only the perfunctory calls. Even the cheerleaders, clear plastic ponchos pulled over their tracksuits, are chanting less frequently. But when their cheers do come, they take on an unintentionally ironic tone.

“Cats, cats, you can do it,” the girls say in unison, “if you put your minds to it.”

Yet the mood among Hannan’s players and coaches is strangely ebullient. Nearly everyone is smiling, even though there are just minutes left in the game and defeat is now inevitable.

Thomas is no longer concerned about winning the game. She just wants to get No. 11, senior Andrew Gillispie, into the endzone.

Gillispie was previously the team’s running back, but volunteered to switch to the offensive and defensive line this season, just to help the team out. Thomas wants to get him a final touchdown to cap off his high school career.

Running back Isaac Colecchia, who has spent the night as the team’s ball boy, produces his iPhone to capture the moment. Qualls hands Gillispie the ball. He dashes for the sideline. When he reaches the 14 yard line, he slips in the mud and fumbles the ball. A Parkersburg player promptly falls on top of it. There will be no touchdown for Gillispie tonight.

The Crusaders run out the clock. Final score, 0–43. The teams form a circle, bow their heads, and recite the Lord’s Prayer. The defensive line smears Miller’s face with mud. Thomas gathers her team for one final huddle of the night. “We gave it a heck of an effort out there,” she says.

They break from the huddle with their customary chant—“One, two, three, FAMILY”—and head back to the locker room.

In her office once again, Thomas removes her wet and muddy rain jacket. She tosses her headset on the desk. Her players, now wearing street clothes, stop by to say goodnight.

“Love ya, Kellie,” Qualls says as he heads for the door.

“Love you, too,” she says.

And she does. Other coaches might have come to Hannan, played a few disappointing seasons, and moved on. But that’s not Thomas.

“I love every one of them as if they were my own,” she says. “I hope I’m coaching football and girls basketball ‘til I have to be carted off. I have no plans of ever leaving Hannan High School.”

For all her knowledge about sports and coaching, this is one thing Thomas has never mastered. She has never quite figured out how to give up.

Zack Harold is a writer based in Charleston, West Virginia, and is the managing editor of WV Living and Wonderful West Virginia magazines.