Jessica Paquette arrived at the Arlington Avenue dollar store around noon on a recent Wednesday. She needed to buy milk.

The 30-year-old mother of two walked through the aisles stocked with confections and party favors to a small refrigerated section at the back. She stood there a few moments, paced for a few more and then flagged down an employee.

“I’m looking for white milk,” Paquette said.

The employee said all they had was chocolate.

Paquette, a new arrival to Mt. Oliver Borough, which is surrounded on all sides by the City of Pittsburgh, threw up her hands and started scrolling through her phone in hopes of finding someone to give her a ride. The employee went back to stocking shelves.

“I’m probably not even gonna worry about it ‘cuz I’m walking,” Paquette said of the milk. “I don’t have a car. I know there’s a Shop ‘n Save down a ways, if you take the 51 [bus]. But I’m not in the mood for all that.”

Her story is not unique.

1 in 5 Pittsburghers

In 2017, more than 1-in-5 Pittsburgh residents were food insecure, meaning they routinely had to choose between food and other basic needs — housing, medicine, education, transportation and utilities — or between reducing portions or skipping meals entirely, per city data.

This, in a city with a resurrected restaurant scene receiving glowing culinary profiles in outlets like the New York Times and Bon Appetit, and no shortage of fine-dining catering to a growing group with more disposable income. While that may attract tourists who dine out, it’s a different story to actually live here and fill kitchen cabinets.

“There’s the dichotomy: It’s a foodie city, but not a lot of people are close to a grocery store,” said Sarah Buranskas, food access coordinator for the Pittsburgh Food Policy Council.

This divide is evident in Pittsburgh-area communities with less disposable income than most, areas the free market has long overlooked. The result? As Paquette experienced first-hand, options are often limited in places like the Hilltop, Homewood and Clairton.

There are a number of reasons for this, including distance, price, topography, walkability and access to transportation and public transportation. Pittsburgh experts urge considering other factors, too, such as sidewalk availability and weather when discussing food deserts.

While geographically distinct, the Hilltop, a dozen communities on Pittsburgh’s southern end; Homewood, technically three eastern neighborhoods; and the City of Clairton, a Mon River town 15 miles southeast of Pittsburgh, are all linked by a lack of access — and people trying to overcome the problem.

Shelly Danko-Day has no illusions about how much work needs to be done. She is Pittsburgh’s urban agriculture and food policy adviser and works to improve food access in the city, build out local food systems and expand the reach of the city’s farmers markets.

“We know we’ve got problems with food equity and food security in the city,” she said. “These are the same places with access issues to parks and hospitals.”

While the city has hotspots where 30 to 70 percent of residents are food insecure, it’s an issue just about everywhere, she said.

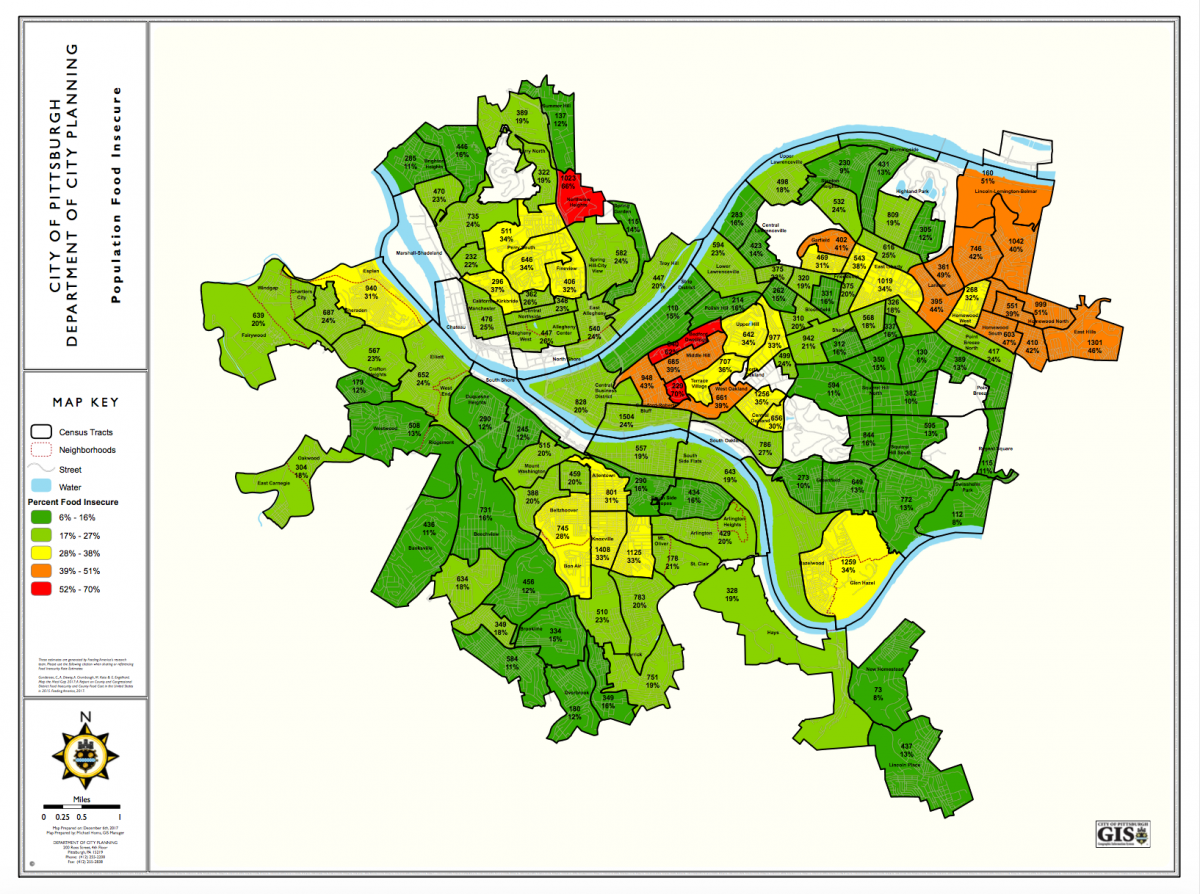

Generally speaking, food insecurity refers to an individual’s ability to afford food. Food deserts refer to their ability to find it nearby. And while food insecurity can exist outside of food deserts, a map of Pittsburgh’s food insecure communities reveals considerable overlap.

The map is a sea of dark green (six to 16 percent food insecure) and light green (17 to 27 percent) punctuated by islands of yellow (28 to 38 percent), orange (39 to 51 percent) and red (52 to 70 percent). Danko+Day said none of these ranges are comforting.

“Green isn’t peachy,” she explained. “That’s still up to a quarter of residents in those areas.”

In the food deserts of Homewood and the Hilltop, food insecurity rates are predictably high, impacting between a third and one-half of all residents.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture measures food deserts based on several metrics of low access and low income, explained Shelly Ver Ploeg of the department’s economic research service. Ver Ploeg also leads the department’s food assistance branch.

Low access areas, for example, can be measured as places where at least 100 households that do not have a car are more than a half mile from the nearest supermarket, super center or large grocery store. Low income areas are defined as places with poverty rates of at least 20 percent or places where the median income is at or below 80 percent of the metropolitan area’s median income, per the USDA.

Among similarly sized cities, a 2013 report from Just Harvest states, “Pittsburgh has the highest percentage of people” residing in so-called food deserts.

This is their story, a chronicle of the food challenges facing Pittsburghers and the DIY spirit of residents and activists who are sick of waiting for a free-market solution that may never come.

‘A story of poverty’

Karin Lysaght of Beechview, a Hilltop-adjacent neighborhood, said she sometimes goes door-to-door taking grocery orders for neighbors without access to a vehicle.

“Whenever we do go to the store, no matter where we’re going, we always ask our next-door neighbor and the gentleman that lives down the street, because he doesn’t have a car. So we’re always asking them if we can pick something up for them,” she said.

Considering vehicle access in the definition, low access areas are places where at least 100 households that do not have a car are more than a half mile from the nearest supermarket, supercenter or large grocery store, per the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“It’s really a story of poverty,” said Sarah Baxendell, director of green space projects with the Hilltop Alliance. The alliance is behind the planned Hilltop Urban Farm at the former site of the St. Clair Village housing project. Once operational, the farm will be the biggest of its kind in the country and a key source of fresh, whole foods for Pittsburgh and surrounding Hilltop neighborhoods.

“If we’re talking about food access, then, from a broad perspective, of the 11 Hilltop neighborhoods, nine are food deserts with no fresh produce of any kind available,” Baxendell said. “Then two neighborhoods, Mount Washington and Carrick, are considered food gaps. Each has one grocery store, and Carrick now has a farmers market.”

Tracy Frank, director of services for The Brashear Association, the South Side-based charity serving families from Hilltop neighborhoods, said food insecurity is an all-consuming issue for some of their clients.

“This becomes their No. 1 focus,” Frank explained. “Everything else — finding a job or finding a better job or getting their kids into middle school — everything else gets put on the back-burner because they have these really pressing food security issues.”

Frank said patronage of the association’s food pantry hit a high around 2009 “where the usage was absolutely ridiculous.” She said the numbers lowered after that but have been rising steadily for the last five years. She theorizes that some of this owes to the relocation of residents who are being driven out of other parts of the city by rising rents, even though they’re rising on the Hilltop, too. They arrive there with the same needs, driving up demand for services like those offered by Frank’s organization.

But Baxendell is skeptical that the arrival of new Hilltop residents will lead to the arrival of new Hilltop grocers or better food access.

An influx of grocers is unlikely given the size of the neighborhoods, the fact that the topography isn’t changing and that the public transit routes are unlikely to change anytime soon, she said. Additionally, a scattered framework of existing grocery store franchises makes it harder to advocate for better offerings or compel changes.

Small-scale interventions are working but with limited impact, she added. Danko+Day said less than 0.25 percent of all food sales in the City of Pittsburgh are happening at farmers markets.

“Some community projects are growing food that’s not for sale and giving it to neighbors, which works well for portions of those communities but does not address the underlying issues,” Baxendell said.

Once a reality, the Hilltop Urban Farm will exist on a much larger scale. Fully active, the farm will multiply Pittsburgh’s food supply by 400 percent and quadruple the amount of food grown within the city limits, based on its acreage.

But that reality is still years away and in the meantime residents like Paquette are still trying to work out the logistics of a run-of-the-mill grocery run.

“I had a cart that I used to use but it broke,” she said. “Without it I probably can carry six to eight bags depending on what’s in them. It’s a lot harder to shop by bus — and that’s if you have bus fare.”

She added, “I’m completely out of milk and bread. And there’s a lot of people that have trouble with the grocery shopping. Now I’m one of them.”

Disenfranchised and disillusioned, a growing number of organizers and activists in places like the Hilltop are turning to homegrown alternatives, like non-profit grocery stores and community gardens, in an attempt to fill in the void.

Gardens sprout in Homewood, where residents ‘decided to grow our own food’

Zucchini, tomatoes, mint, beets, strawberries, and raspberries grow in 17 raised beds in a vacant lot on North Braddock Avenue, thanks to Ayanna Jones. Along with what used to be a notorious drug corridor in Homewood, Jones is growing gardens — and, more importantly, she said, she’s growing gardeners.

When Jones, 70, grew up in Homewood, her family chose between three grocery stores in town — “everything that we needed was in walking distance,” she said. Now, there’s not a single one, though a bumper crop of grocery stores has sprouted in nearby East Liberty.

Rev. Ricky Burgess represents Homewood on Pittsburgh City Council. He grew up there and remembers when the town had multiple grocery stores. Now, he said, he’s “acutely aware of the fact that there’s no place to get fresh vegetables,” and he’s courted stores to open there, but hasn’t been successful yet. So why aren’t stores interested?

For three reasons, Burgess said: First, a grocery store needs a high volume of shoppers from a variety of income levels. Second, stores see the potential for theft in poor communities. Finally, he said, the perception of safety becomes an issue.

Burgess continues to try to open a grocer, suggesting a food co-op in Homewood, adding more farmers markets and continuing discussion about rebuilding the business district to include a grocery store.

Jones’ community garden is one of several established in the past few years as urban agriculture fills the gaps for fresh produce.

Three years ago, Jones founded Sankofa Village Community Garden with the help of Sankofa Village for the Arts and several community grants. The Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh owns the land, and Sankofa is in the process of purchasing it. Kids from Sankofa’s summer camp and the Learn & Earn program built the garden from the ground up — assembling the raised beds, adding compost, building an irrigation system, planting and harvesting.

When Jones works in the garden, located in a prime location at the corner of North Braddock Avenue and Susquehanna Street, just about every passerby shouts hello or honks their horn. She hands out tomatoes to local families and takes fresh produce to those who can’t leave their homes.

Tirelessly, Jones now plans to build a greenhouse at the garden and to renovate an old house next door to offer a kitchen for kids, so they can learn to cook using the vegetables they grew and even bring home-cooked dinners to their families during the week.

Across the nation, black and Hispanic neighborhoods are home to fewer large supermarkets than their white counterparts, according to research from Johns Hopkins University. The smaller stores available in those neighborhoods usually don’t sell healthy whole-grain foods, dairy products or fresh fruits and veggies, the report found, adding that farmers markets can help fill the gap.

“If we don’t start educating our young black children about gardening and the importance of urban agriculture, we’re not going to have that sense of feeding ourselves,” she said. “We’re starting to really affect young people in terms of the importance of growing food.”

A few blocks from Sankofa Village Community Garden stands the Homewood Historical Urban Farm, run by Black Urban Gardeners and Farmers of Pittsburgh Co-op (BUGs). Raqueeb Bey founded and runs the group, which farms on a 31,000-square foot formerly blighted lot. BUGs recently built a hoop house on the lot, so they can grow food all year.

In addition to Sankofa and the BUGs farm, Homewood is also home to Operation Better Block, Oasis Food, the Monticello Street Garden and the African Liberation Garden, along with 210 backyard gardens, installed for free by Phipps Conservatory Homegrown program, according to local leaders.

While 210 gardens is already a lot, it’s estimated that the reach of those gardens spreads even wider. On average, one gardener shares their produce with about nine different people, according to Lauren DeLorenze, Community Outreach Coordinator for Phipps Conservatory, who works closely with the Homegrown program.

“When we think about food deserts, it’s not just a geographic issue. It’s certainly an economic issue,” said Gabe Tilove, associate director of Adult Education and Community Outreach for Phipps Conservatory. “We do see backyard gardens as one way to supplement tight food budgets with fresh produce, and it’s a way to get kids excited about vegetables, which is difficult for any family.”

BUGs, along with other groups concerned about food access, formed the Homewood Food Access Group. The collective power of those groups merged to create the monthly Harambee Backyard Market, part farmer’s market, part arts festival.

“This is a dire strait. No resident should have to leave their community to go grocery shopping. … Some people don’t have access to a car,” said Bey, who also works as Grow Pittsburgh’s garden resource center coordinator. “You may work two jobs. Or you may be a single parent and have to lug two or three kids with you. You may be a senior. You may be ill. Having a localized grocery store is important.”

After years without a grocery store, a new kind of market comes to Clairton

For more than a decade, Clairton hasn’t had a grocery store. There have been attempts to lure a chain store and talks about the possibility, but nothing stuck.

Currently, there are two dollar stores and a Rite-Aid to buy some groceries. A Speedway opened and quickly became a popular spot for residents to buy prepared foods and to serve as a gathering spot.

But none of those places offer fresh foods daily.

That changed when Produce Marketplace, a nonprofit grocery store, opened Oct. 27 at 519 St. Clair Ave., along one of Clairton’s main thoroughfares.

The store is filled with produce and fruit, as well as some breads, frozen meats and dairy. Dry goods will be limited — enough so shoppers can pick up everything for a meal in one trip, but not so much as to compete with the nearby dollar stores, said Josh Berman, director of community food initiatives for Economic Development South, a nonprofit that builds partnerships in various municipalities to aid community development.

The aim is to keep prices down and accept SNAP and WIC benefits. As of 2016, 30 percent of Clairton lived below the poverty line, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

For Madge Bristow-Norman, shopping at Produce Marketplace is a way to support her community. She said she can drive to the store, but shopping at the mobile market ensures it has enough business to keep coming back for the people who need it.

Bristow-Norman and others all stressed the bond that the residents of Clairton have and the sense of family there is, boasting about community programs and the close ties among residents.

If the store eventually becomes profitable, the goal is to turn it over to an entrepreneur who could then make it their business, and EDS would replicate the model somewhere else.

Felix Fusco, a lifelong Clairton resident and avid community volunteer, is the store’s one employee.

So he knows the new store will be more than a place for vegetables; it will be a community spot. He’s full of plans, too, to get more people in the door — a bike share to help shoppers get their groceries home, regular food delivery to the nearby senior apartments and free fruit for any kid that comes in after-school.

“This is the fun part,” Berman said.

This article is a culmination of a four-part series by The Incline. Read all four stories here.

This story was supported by The Pittsburgh Pitch, a project of 100 Days in Appalachia and the Center for Media Innovation at Point Park University.