West Kentucky farmer Judy Wilson says her family is a bit of a sundry bunch.

“We love the farm, but we also love all the nature,” she said.

Wilson is driving down a back-country road that divides two fields, to the left is her soybean crop and to the right is 102 acres that she has placed in the Wetland Reserve Enhancement Program, something her husband always wanted.

“After he died my daughter and I decided to go for it,” Wilson said. “That’s low ground so that all would flood.” The WREP allows her to live out her husband’s legacy.

Photo credit Nicole Erwin, Ohio Valley Resource.

WREP is a U.S. Department of Agriculture program funded through the Farm Bill. It offers landowners the opportunity to protect and restore wetlands on their property. Landowners like Wilson are paid for each acre of farmland taken out of production permanently.

Wilson explained that the farmers in the area are at the mercy of the mighty Mississippi River.

“It’s always been flooding. But it does seem like more,” she said. “It seems like more land has been maybe cleared and so it’s affecting more land.”

The more land that is cleared the more likely the area will flood. But to what degree? Murray State University was recently awarded $1.36 million dollars by the National Resources Conservation Service and The Nature Conservancy to explore the impact of wetland restoration from local habitat protection and flood control to reducing the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico.

Photo credit Nicole Erwin, Ohio Valley Resource.

Nutrient Overload

Howard Whiteman, the principal investigator on the project with Murray State, said it’s important to get a grasp on the program’s full effects.

“There hasn’t been a study that has been comprehensive,” he said, “on either the watershed itself or on the water that ends up down in the Gulf of Mexico.”

The grant allows Whiteman and his team to explore the benefits of restoring flood-prone farmland in western Kentucky into bottomland hardwood forest in part to reduce the flow of excess nutrients into the Mississippi River.

Nitrates from agricultural, industrial and urban runoff create areas of low oxygen, or hypoxic zones, where marine life struggles to survive. The Gulf of Mexico has the second largest hypoxic zone in the world.

Murray State biologist Michael Flinn wants to better understand how the water drained from the Mississippi River into the Gulf could be filtered through soil.

“We want to know what is the concentration of nutrients that exists in that water when it starts to flood. And then what is the concentration of the nutrients in that water when it goes back out into that channel, after that restored wetland has had a chance to chew on it,” Flinn said.

Rising Flood Problems

The Pew Charitable Trusts reports flooding is the fastest-growing, most costly type of natural disaster in the U.S., and long-term climate data show that parts of the Ohio Valley are highly vulnerable. The federal government’s National Climate Assessment shows that over the past 50 years heavy downpours, linked to flash flooding, have increased at a higher rate in parts of the Ohio Valley than anywhere else in the country.

Land use can, of course, determine where the water goes in those heavy rains, and farms play a role. Over the years wetlands have been stripped and drained to grow crops. And as waterways have been channeled to work with farms and ditches, many of the natural twists and turns that regulate momentum in streams have been removed.

Those features are also habitat that some wildlife depend on, such as the endangered relict darter fish that lives in the Bayou de Chien, a waterway in the Mississippi floodplain in western Kentucky.

“It’s endemic. It’s not found anywhere else in the world except in the upper watershed of Bayou de Chien, which is really interesting,” Shelly Morris said. She is project lead for the Nature Conservancy. “By taking these lands and putting them back into conservation cover, providing habitat, providing better cleaner water, we’re impacting everything,” she said.

Farm Bill Effects

The WREP could become more important as other wetlands protections come under assault. Under the Trump administration, the Environmental Protection Agency is attempting to repeal the 2015 application of the Waters of the United States rule, also known as the Clean Water Rule. This would remove protections placed by the Obama administration on areas including wetlands.

The final comment period closes August 13.

The Farm Bill being debated in Congress could have significant effects well beyond farms, including on our waterways.

Kellis Moss, Director of Policy for Ducks Unlimited, said that as flooding becomes more frequent, funds provided by the Farm Bill will be more competitive for future applicants who wish to enter into the program.

Kellis Moss, Director of Policy for Ducks Unlimited, said that as flooding becomes more frequent, funds provided by the Farm Bill will be more competitive for future applicants who wish to enter into the program.

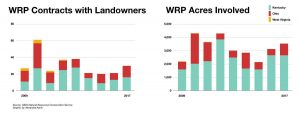

The House version of the 2018 Farm Bill could cut nearly $800 million in overall conservation easements. But Moss said both the House and Senate appear to increase funding for the wetland restoration program.

“Demand for wetland reserve easements have been through the roof and continue to be,” Moss said. “I think some of these producers realize that they are struggling to make a profit off some of this very wet land that keeps getting flooded.”

This is where Murray State researchers and the Nature Conservancy feel science can also help.

“Everyone is operating with limited dollars,” TNC’s Shelly Morris said. “So, where are you getting the most bang for your buck? Where can we best spend our dollars to get the most conservation impact?”

Howard Whiteman said he is excited about the five-year study, not only for the groundbreaking work but for the opportunity it provides for his students.

“We are breaking new ground in terms of restoration monitoring, our results will aid the planning of future restoration efforts here in Kentucky as well as throughout the Mississippi basin,” Whiteman said. “Similar projects are starting to take root in Tennessee and elsewhere in the basin but ours is the first. We hope to make it the standard by which these newer projects are judged.”

Building A Legacy

Farmer Judy Wilson looks forward to a new sort of crop on her farm. Instead of soybeans, eventually her wetlands will be lush with nut trees, deer and waterfowl like the great blue heron, ducks and bald eagles.

“One day we came up here and there were 25 eagles,” Wilson said. “When the water goes down the fish that are in there or just left high and dry and the eagles were just having a buffet,” she said, looking out on the conserved land.

“Just look how pretty that is.”

This article was originally published by Ohio Valley Resource.