The craft brewing scene in Asheville, North Carolina, began with one brewery. Highland Brewing Co. opened in the basement of Barley’s Taproom in 1994, using jury-rigged dairy equipment to make British-inspired beer. At the time, there were only a handful of restaurants and bars downtown, most buildings were boarded up and Budweiser was still the king of the taps.

Things have changed over the last 24 years. With over 60 breweries in the region employing hundreds of people, what started as a niche scene has become a full-blown industry and a key part of Asheville’s economy.

Around the same time the seeds of Beer City were sprouting, the restaurant and bar scene in the city began a trend of steady growth. The synchronous development created a service industry economy that employs almost 30 percent of the city’s population, according to Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce. It’s a two-headed beast with two distinct personalities — breweries, steady and confident; and restaurants, which are more fickle, constantly tossed about by changing food costs and exceedingly narrow margins.

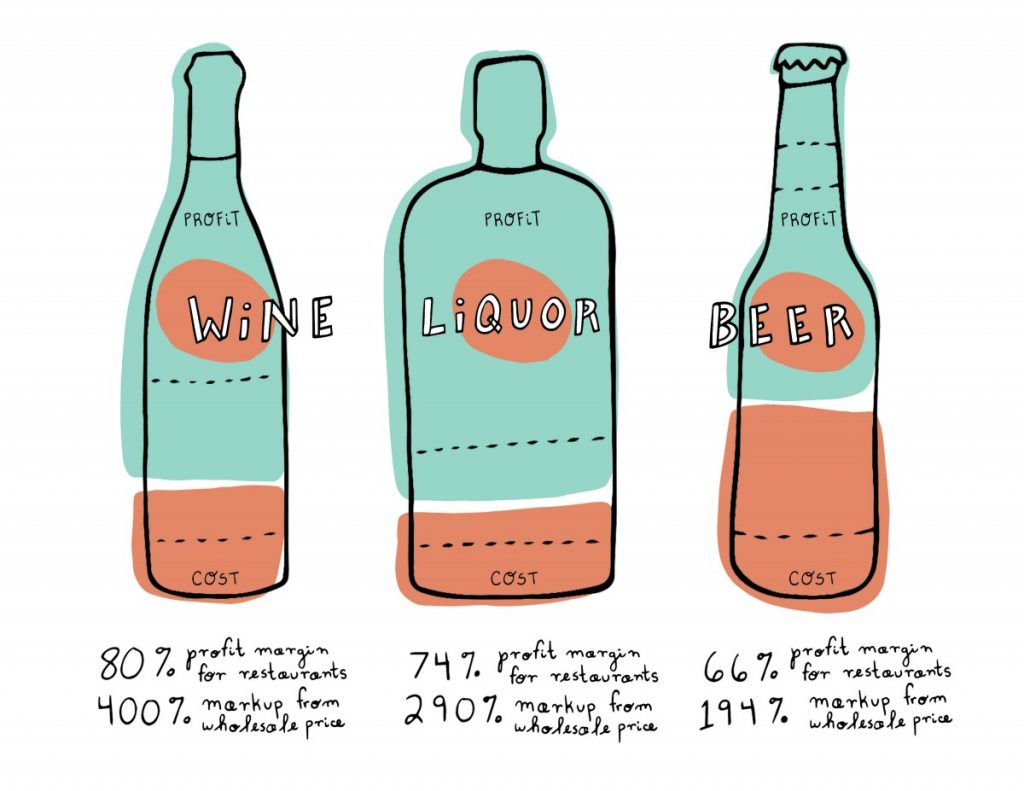

Restaurants run on razor-thin margins, usually around 15 percent before labor and overhead, so they tend to rely on much more generous alcohol margins — which often dance between 60 and 80 percent — to make their income.

“Our food margins are so expensive because pig is our top seller, and it is our most expensive product,” says Kyle Beach, general manager of Buxton Hall Barbecue. “It’s around $8 a pound before it is processed, and that’s not counting labor or the cost of wood (for smoking). So for us, alcohol is a big part of the profitability model.” Beach says 25 percent of the overall sales for the restaurant are from alcohol, and 60 percent of alcohol sales are from beer.

Traditionally, wine and spirits have been the most consumed beverages at restaurants, so their markup has been more sizable. But as Asheville’s reputation for great beer encourages more diners to order a lower-margined ale or IPA with dinner, restaurants may have to tighten their belts as overall profit margins begin to shrink. If there is a major shift toward diners opting for beer over wine or cocktails, it could put a chokehold on a market already stretched thin by saturation.

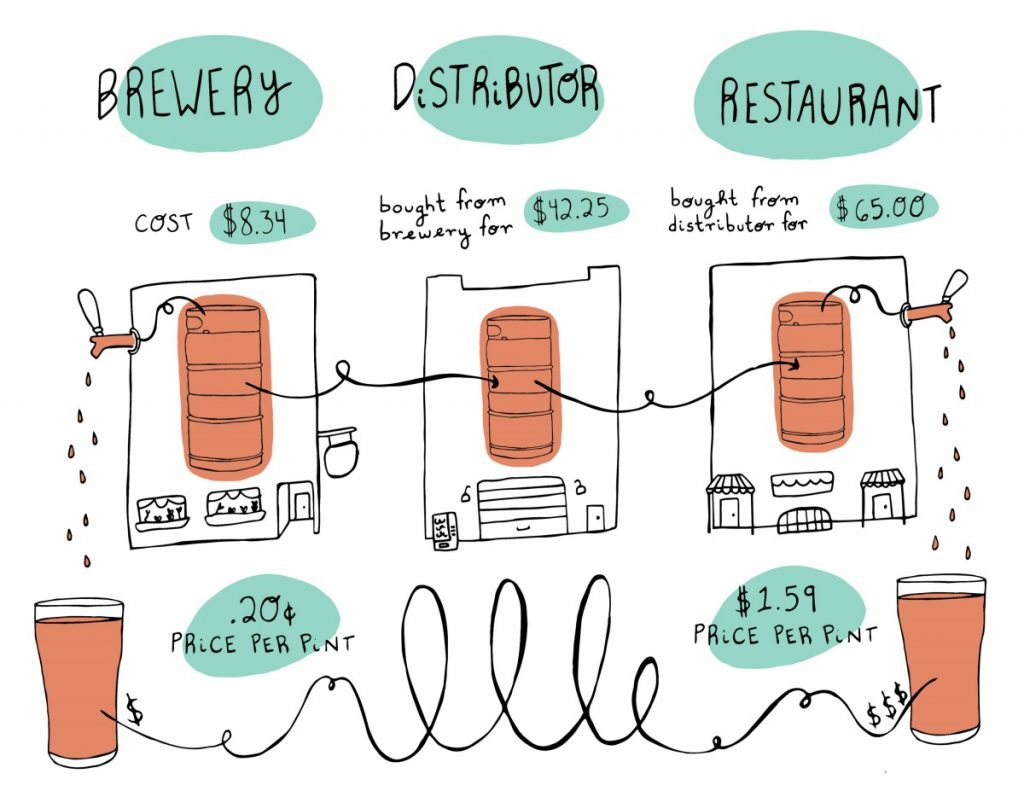

Here’s a quick look at how those margins work out and how booze is priced in a restaurant. (Note: The following numbers were gathered from local distributors and restaurants, and do not factor in labor or overhead, only cost of goods.)

Take an $8 glass of wine, for example. Since wine goes bad quickly — most restaurants only keep an open bottle for about three days — restaurants traditionally price it at the cost of the bottle. That way, if only one glass is sold in three days, the business at least breaks even. So if a restaurant pays $8 for a bottle of wine and will get five glasses out of it, charging $8 per glass means a $32 profit for each bottle, and $6.40 per glass, but only if customers drink every drop. That is an 80 percent margin at a 400 percent markup.

Liquor tends to run a more flexible line. Nicer liquors, like that $32 bottle of Bulleit bourbon, can be sold for $10 per pour with a profit of $7.44 per pour. That is a 74 percent margin with a 290 percent markup.

But beer gets trickier because it’s sold in varied packaging — multiple keg sizes, bottles and cans. In their taprooms, most big brewhouses serve from full-sized 15.5-gallon kegs, known as “half-barrels.” But most Asheville restaurants don’t have the space for kegs that size, so they rely on the smaller 5.2-gallon kegs, or “sixth-barrels.” Those can cost a restaurant anywhere from $65 to $90.

A sixth-barrel keg of Green Man IPA, which would contain about 41 pints, costs a restaurant $69.50, or $1.70 per pint, assuming there is no loss or foam. Most Asheville restaurants fix their pint prices at $5, which means $3.30 per pint profit, at a 66 percent margin and a 194 percent markup. That’s just $135 profit per keg, compared with $93 profit for that single bottle of bourbon or $384 profit for a case of wine.

“People get mad if they have to pay $6 for a pint,” says Zoe Dadian, who has managed Cucina 24, Tod’s Tasties and, most recently, the now-shuttered Local Provisions. “We get all this flack about, ‘Why don’t you pay your workers a living wage?’ We’re trying; we’d really like to. But there are more breweries every single day.”

“Look at the difference in the margin,” says Schultz. “A brewery has a super high margin. But we’re paying between $65 and $95 for a six barrel (plus a $30 deposit on the keg), and that doesn’t account for foam and waste on the keg. So they can go down to the brewery and get a $4 pint, and it’s the same thing we are charging $6 for, and we are still making less charging more!”

A restaurant can grab $65 sixth-barrel from a moderately priced brewery like Catawba or Asheville Brewing, but how do we arrive at that price? The Brewers Association averages that a 31 gallon barrel of beer costs the producer $50 to make. That means that a sixth-barrel can cost them as low as $8.34. They then sell that barrel to their distributor for $42.25 and the distributor then adds 30 percent giving the restaurant a $65 price tag. That means that the brewery is making roughly $33.91, generating an 80 percent margin on a 406 percent markup.

A Brewers Association article published in 2016 titled “The Brewpub Advantage” estimates that brewpubs, which function as both restaurants and tasting rooms, can make anywhere from 26 to 46 percent of their sales from beer, and at those generous markups can see a barrel of beer turn into a return of up to $800. With a $25 cost for a half barrel of beer, that comes out to roughly $0.20 per pint. That means that the $5 pint you get with your fish and chips at the local brewpub can have as much as a 2,400 percent markup at a 96 percent margin. That’s an astoundingly high markup by comparison to a local eatery.

Asheville restaurants generally try to stick to the national average of a 15 to 30 percent margin, and many err closer to the lower end of that scale. “I don’t know anyone that is running a 30 percent food margin,” observes Sovereign Remedies owner Charlie Hodge.

That means a $15 dish at an average downtown eatery can yield a profit as low as $2.25. If a customer orders an $8 glass of wine with the meal, it brings the total profit for that diner up to $8.65. But if instead she chooses a $5 beer, the restaurant would come away with closer to $5.55. That difference of 43.66 percent, or $3.10 in profit can really add up over the course of a dinner service, let alone over the course of a year.

“We are charging $6 for a pint, which is more than most, and even with that, our margin by comparison to wine or a cocktail is so much smaller,” says Rhubarb’s bar manager, Spencer Schultz. Rhubarb tends to sell mostly wine and cocktails, with beer accounting for about 20 percent of its alcohol sales — which is a good thing, says Schultz. “We couldn’t make the percentages we need to make just on beer,” he points out. He has started urging guests to try bottled sour beers and goses, which he says both tend to pair better with Rhubarb’s food and give the bar a friendlier margin.

“I think the big problem is that Asheville (restaurants have) a fixed beer price, which is $5 to $6 a pint more or less, and everyone is breaking their cost control metrics to keep that price point,” says Beach, noting that much of that price suppression comes from brewery tasting rooms that keep pint prices on staples like pale ales and lagers at around the $3 to $4 mark In cities like New York, Washington D.C., Atlanta, and even Charleston, South Carolina, and Charlotte, beer draft prices for craft beer can reach as high as $8 to $10.

This does present a bit of a quandary, in terms of pricing for the industry. If a brewery were to push their pint prices to that $6 to $8 mark to encourage restaurants to raise their prices, that would result in a 2,900 to 3,900 percent markup, gauging the market even further. In North Carolina, since alcohol is considered a regulated substance, distillers are required to sell the liquor they produce to the state and then buy it back before they are allowed to serve it in their own tasting rooms. Local breweries like Catawba Brewing Co. have started mimicking that type of structure to keep their prices on par with bars and restaurants, but it is important to bear in mind that they are still buying the product from themselves.

“Catawba is one of a slew of tasting rooms that have raised their prices in recent years,” says Catawba retail operations and marketing specialist Brian Ivey. “As far as comparing our prices to restaurants and bars, we internally charge our tasting rooms for beer as if they are a bar. So they ‘pay’ the same price for a keg as a local establishment that buys through distribution. This ensures that we understand what it costs to run a tasting room.”

“The problem is that in a lot of those bigger cities that are charging more for beer, you have a higher median income, so they are willing to pay for an $8 beer and still come out just as often,” says Emilios Papanastasiou, who runs Post 70, Post 25 and the East Village Grille. “But in Asheville you have a lot people still under that living wage ceiling that can barely afford covering rent, so they aren’t going to want to go spend that much for a draft beer.”

East Village Grille has $5 pints with a rotating $4 special and runs weekly beer specials of $4 drafts. “It’s just a sales driver,” says Papanastasiou. “We take the hit on the alcohol to try to fill the restaurant up on a Monday night.” But that means leaning heavily on already thin food margins.

It may be that Betteridge’s law of headlines applies here: When the headline of an article asks a question, the answer is always no. Perhaps it’s hyperbole to ask if Beer City could kill Foodtopia — maybe it would be more of a squeeze. But without some creative adaptation, the steady rise of beer drinkers could throw a wrench into the way restaurants survive, driving up either the cost of food or the cost of booze.

Jonathan Ammons (@jonathanammons) is a writer, eater, drinker, bartender and musician based in Asheville, North Carolina.

All illustrations by Emily Prentice (@_emily_prentice_).