President Trump’s Thursday announcement of a national public health emergency on the opioid epidemic is already being criticized by some who are calling an unfunded mandate – Democratic House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi responded by calling it “words without the money.”

But it is, at least, a start. And that’s better than nothing.

I have not been optimistic that Trump would follow through on his vow to address the opioid crisis, given that Thursday’s declaration was promised once before but delayed. I was worried that Candidate Trump would forget about the painkiller epidemic when he became President Trump.

But he has not, and I’m cautiously optimistic. First, though, the critics are partly right. Trump’s declaration amounts to regulatory reshuffling that should provide some help by allowing federal agencies to redirect existing funding. However, it lacks the vision, scale – and major funding – to wipe out this public health crisis in the way that polio, small pox and influenza were effectively ended.

What’s positive: The president’s plan will lift a law barring health providers from using telemedicine, or video and phone communication, to remotely prescribe drugs for substance abuse. This may seem esoteric but it is not in rural states, which have been hit the hardest by the opioid epidemic, and where travel to distant health providers and treatment clinics is difficult.

The White House is also instructing agencies to end bureaucratic delays for handing out grant money and to move some federal grants toward fighting the epidemic.

Finally, the White House said it would work with Congress to obtain additional funding. That’s critical, because what’s missing in so many communities is instant treatment for those suffering from opioid addiction and who want help. Police officers lament that it can take 30 days to get a patient into a treatment center, if indeed one is available, creating more time for the possibility of a fatal overdose. Fully funded walk-in treatment facilities are needed, regardless of the patient’s insurance or lack of it.

How bad is the problem? Sales of prescription opioids nearly quadrupled between 1999 and 2010, said the Centers for Disease Control, as pharmaceutical companies and health providers combined to fuel the then-new concept of pain management. The CDC said 91 Americans die each day from an opioid overdose.

It is encouraging to see the president at least begin to talk about this issue, because, aside from low-skill job loss, opioid addiction is probably the biggest problem in states that voted for Trump.

In West Virginia — where nearly 70 percent of voters went for Trump during the 2016 election, making it the nation’s No. 2 Trump state after Wyoming — 5 percent of babies born last year were born drug-affected, according to the West Virginia Health Statistics Center. First Lady Melania Trump visited a drug treatment center in Huntington, W.Va., that helps infants who were exposed to addictive substances during their mother’s pregnancy.

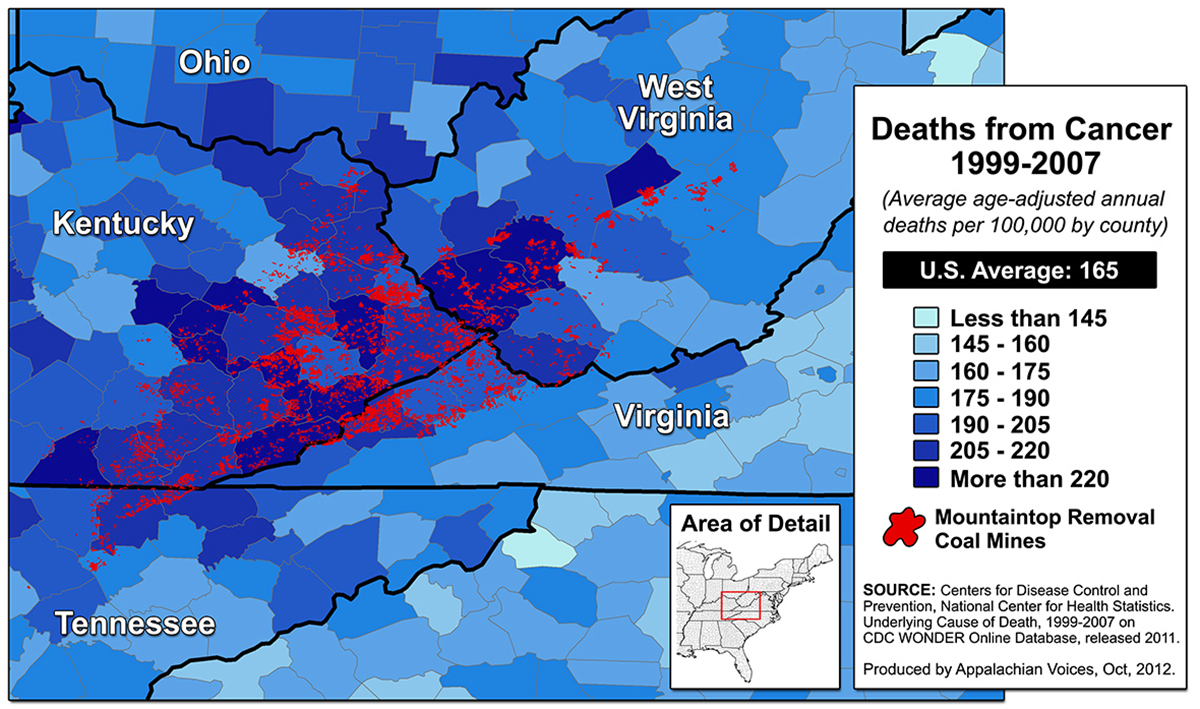

The death rate from opioids in West Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio – all Trump states — is more than twice the national average.

A typical and too-easy path to opioid addiction starts from their legitimate prescription to treat pain suffered in on-the-job injuries. These are more common in Trump-friendly, heavy-industry states, such as West Virginia, with its coal mines and chemical plants.

Workers get injured, are prescribed powerful and addictive medicines such as Oxycontin and Tramadol, and soon get hooked. No longer do they need the opioids just to fight the pain of their injuries; they need the opioids to fight the pain of withdrawal if they can’t get the pills.

And it has been too easy to get the pills.

The Charleston (W.Va.) Gazette-Mail won a Pulitzer Prize this year for its jaw-dropping reporting that showed drug distributors had flooded West Virginia, a state with 1.8 million people, with 780 million opioid pills over a period of six years, leading to 1,728 fatal drug overdoses.

Drug companies shipped 9 million – 9 million – hydrocodone pills to a single pharmacy in Kermit, W.Va., population 392.

In situations like this, where prescription narcotics are as much a part of the environment as coal dust, it’s almost impossible not to encounter them, to prevent criminals from peddling them and to avoid addiction. In short, they have become normalized.

That’s one element of Trump’s announcement that shows an unfortunate naivete about the scope and depth of the problem. In addition to the policy measures he announced, Trump also promised “Really tough, really big, really great advertising so we get to people before they start. If we can teach young people not to take drugs…it’s really, really easy not to take them.”

There is certainly a place for educational advertising to help fight any public health crisis. It’s clear that the government’s anti-smoking ad campaigns have been effective. So effective that more Americans now use prescription opioids than smoke cigarettes.

Yet it’s not young people who are addicted to opioids. Opioid addicts are typically white, middle-class Americans, the majority of which are over 65. More to the point, even government research has shown that its own youth anti-drug media campaigns were not effective in reducing youth drug use.

No one wants to be addicted to opioids, or anything else. Studies link painkiller addiction with joblessness and other negative outcomes. Many sufferers who want help not only can’t get it, they may be ashamed to ask.

So as much as anything, the value of Trump’s announcement may be that it helps reduce the stigma of opioid addiction. C. Everett Koop, the late U.S. Surgeon General under President Reagan, did as much as anyone to change American attitudes about HIV/AIDS patients with his relentless and high-profile public message that “we are fighting a disease, not a people.”

Trump’s announcement doesn’t have that power, but it is a first step.

Frank Ahrens, a West Virginia native, is a public relations executive in Washington D.C. He was a Washington Post journalist for 18 years and is the author of “Seoul Man: A Memoir of Cars, Culture, Crisis, and Unexpected Hilarity Inside a Korean Corporate Titan.”