Some days, West Penn Hospital nurse Kayla Rath barely has time to eat.

“If you could take a lunch break by three or four o’clock and just scarf down your food, then that was a good day,” she said.

Rath, a postpartum nurse at the Pittsburgh hospital, said the past 18 months have been especially stressful. Caring for vulnerable newborns and their mothers throughout the pandemic has been fraught with uncertainty.

“There’s not a lot of research on the effects of COVID in those populations,” Rath said. “And to keep going into work and kind of act like everything was normal was really hard.”

Adding to Rath’s anxiety are the effects of a national nursing shortage that predates the pandemic. Nurses are retiring or otherwise leaving the profession, and nursing programs aren’t enrolling and graduating the number of students needed to fill the gap.

That translates into an almost daily lack of staff in Rath’s unit. Members of the unit’s Facebook group regularly post requests for help to cover shifts. “You essentially don’t know what you will walk into at work every day,” she said.

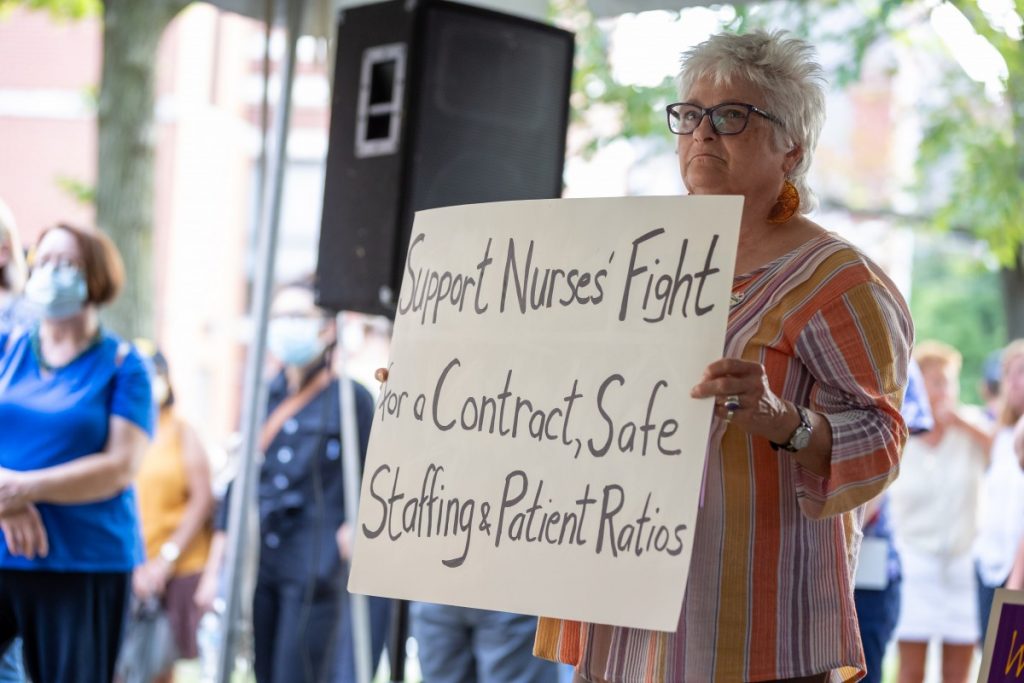

Last month, Rath and about 700 other nurses at West Penn ratified their first contract a year after joining SEIU Healthcare Pennsylvania, a union that represents about 4,000 hospital workers in the state. The contract provides guidelines for nurses and hospital management to address staffing challenges, pay raises – including a 25-year pay scale that takes into account the experience of nursing professionals – and caps health insurance premium increases.

Nurses negotiated with hospital management for nine months to reach the agreement. The process was not smooth. On July 28, they voted to authorize a strike.

Three weeks after the vote, the nurses had a contract without actually striking. Rath was relieved.

“We’re just really glad to be protected,” she said.

The successful organizing activity of nurses at West Penn throughout the past year is one of several examples of recent worker organizing efforts in Pittsburgh.

The city as well as central Appalachia at large are known for their storied and sometimes violent labor histories. The Homestead Strike in 1892 involving steel workers in southwestern Pennsylvania and the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921 involving coal miners in southern West Virginia are two such events in the region that changed the way workers organized, sparking the rise of union membership across the United States. By 1954, more than a third of all U.S. workers belonged to a labor union.

But in 2020, a Pew Research Center study showed that fewer than 11 percent of workers belonged to a union. The decline of union membership over the past several decades has been precipitous, but Pittsburgh is experiencing a moment in new unionization – one that reaches beyond the nursing ranks at West Penn.

A Class of Tech Workers and Google

Ben Gwin, a tech worker for Google subcontractor HCL America in Pittsburgh, can see West Penn Hospital from his apartment window. He understands nurses’ experiences when it comes to unionizing – he’s been through it himself.

In September 2019, about 80 HCL tech workers in Pittsburgh voted to unionize, affiliating with the United Steelworkers Union (USW). After almost two years of negotiations, they agreed to a contract in July 2021. The deal included an average 9 percent raise for workers, spread out over three years.

“Previously, our raises were something like 0.7 percent,” said Gwin, who helped lead worker efforts to organize at the company. HCL also agreed to correct pay disparities and provide more paid time off to its employees.

HCL workers in Pittsburgh are part of Google’s temporary, vendor or contract staff, known in the industry as TVCs. Pittsburgh’s Google TVCs’ vote to unionize came six months after the New York Times obtained documents showing that Google employed more contract workers than full-time employees – paying them less and without the benefits of Google employees, even though they often worked side-by-side with them at locations around the country, including Google’s Bakery Square offices in Pittsburgh.

Gwin said HCL workers had no paid sick days. And he and his fellow workers were also subjected to regulations around paid time off that Google employees were not. HCL workers had to use PTO to take some holidays off, including Martin Luther King Day and Presidents Day. For Google employees, those were paid holidays.

“HCL kept saying ‘we’re just doing what Google tells us to do,’” he said.

Right after HCL workers voted to unionize with United Steelworkers in 2019, they started looking over the employee handbook in detail. “That’s when we learned that managers were just making up some of the rules,” Gwin said.

Mike Maffie, a professor at Penn State University’s School of Labor and Employment Relations, used the term “fissuring” to describe Google’s practice of contracting some of their labor costs out to companies like HCL. “By outsourcing those costs, Google maximizes their profits,” Maffie explained.

Alphabet, Inc., the parent company of Google, generated more than $160 billion in revenue and a net income of $34.3 billion in 2019.

“Those profits benefit Google employees, but not the contract workers,” Maffie said. “It also contributes to Google’s ability to talk about the six-figure salaries their employees enjoy.”

Maffie compares Google’s tactics with similar events at Microsoft in the 1990s. Several thousand independent employees contracted to work for Microsoft, who referred to themselves as “permatemps,” sued the tech giant. They argued they were performing the same work as Microsoft employees and were entitled to the same benefits.

After an eight-year court battle, Microsoft agreed to a $97 million settlement in 2000. The New York Times reported the settlement as “one of the largest ever received by a group of temporary employees” at the time.

Workers in the tech industry have steadily organized in Silicon Valley in the decades since.

In November 2018, more than 20,000 Google employees staged a one-day walkout to protest what they said was mismanagement of sexual harassment claims at the company.

In 2019, they stood in solidarity through social media with HCL workers like Gwin.

“Many of our TVC colleagues work without benefits or adequate pay,” they announced from the Twitter account Google Walkout For Real Change. The tweet also noted that paying workers fairly was “a question of will, not resources.”

In January of this year, Google workers along with other Alphabet, Inc., employees unionized, agreeing to be represented by the Communication Workers of America (CWA).

Membership among Google’s ranks in the CWA tripled in a week.

Unions Have Always Adapted

The organizing efforts of tech workers in Silicon Valley and in Pittsburgh are examples of the way unions are adapting to a changing workforce.

CWA has roots representing telephone companies in the opening decades of the 20th century. SEIU Healthcare Pennsylvania is one branch of a union founded in Chicago in 1921 to represent janitors, window-washers and elevator operators.

In Pittsburgh, workers across a range of professions have joined the United Steelworkers Union over the past few years. Employees in the city’s Carnegie Library System voted to unionize under USW in August 2019. Carnegie Museum employees voted to join USW by a 4-to-1 margin in December 2020. Faculty at the University of Pittsburgh are now in the middle of their own vote to unionize, again through USW.

Gwin said he and fellow worker organizers at HCL chose the USW union for a few reasons. USW’s headquarters in Pittsburgh are a short bus ride away from their location at Bakery Square, and “they have a history of working in non-traditional spaces when it comes to worker organizing,” he said.

“We actually have a lot of experience in representing people who aren’t steelworkers in Pittsburgh,” Mariana Padias, assistant director of organizing for USW, said. Padias notes that the full name of the union is the United Steel, Paper and Forestry, Rubber Manufacturing, Energy Allied, Industrial, and Service Workers.

Quite a mouthful.

What’s changed in recent years for USW is the organizing of workers from non-manufacturing sectors of the labor force into their ranks. “Workers at cultural institutions, like the libraries, like the museums, that is new,” Padias said.

The work itself may be vastly different, but the common link between these workers, according to Padias, is that they all live and work in the same city. “Our union has been kind of trying out a geographic model of organizing,” she said.

Working conditions and the level of violence in labor conflicts have changed, too. “People no longer get shot,” said Padias. Tech workers like Gwin don’t face armed Pinkerton Guards and the potential for violent conflict like coal miners and steelworkers did a century ago.

But like Microsoft and Google in recent years, Carnegie Steel was earning record profits in the late 19th century. In 1892, the year of the Homestead Strike, the company earned a record $4.5 million in profit. Union workers and the protections they demanded were seen as holding the company back.

Henry Clay Frick, who ran steel operations for Carnegie, actively recruited replacement workers for members of the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers who were pushing for a pay raise. He also hired 300 Pinkerton Guards to patrol the Homestead Facility. In the Battle of Homestead on July 6, 1892, seven workers and three Pinkertons were killed; the town and steel mill were then secured by 8,500 members of the National Guard.

21st century union-busting tactics may be less bloody, but they still exist, workers say. In 2020, the National Labor Relations Board filed a formal complaint against HCL, alleging that the company was shipping bargaining unit jobs to a facility in Krakow, Poland. The move was seen as a response to HCL workers efforts to negotiate a union contract.

“We’ve had a firing freeze for our office, and as people have been leaving, they’ve been offering to replace them in Krakow,” HCL employee and bargaining unit member Josh Borden told Vice News in 2020.

Freelancers, Unions and the Gig Economy

The rise of the gig economy is pushing unions into even more new territory.

One pre-pandemic estimate calculated that 34 percent of the U.S. labor force was involved in the gig economy, and although current laws prohibit most freelance workers from forming collective bargaining units, union resources can still benefit freelancers and independent contractors. Understanding how much to charge for their services is one example.

The Steelworkers Union learned from its experience with Pittsburgh’s HCL contract workers.

The efforts of the city’s HCL employees revealed a narrative that complicates Pittsburgh’s transformation from a declining, polluted Rust Belt city to a tech hub on the rise, USW’s Padias said.

“It turns out there’s just like a whole workforce around and underneath that aren’t these super well-paid, highly benefited jobs,” she said. That includes HCL employees and freelance workers.

Freelancers and contract employees don’t have an employer, which means they aren’t protected against discrimination or harassment. There are no overtime laws protecting them either, nor groups that help them understand how to value their work or understand changes to regulations of their industries.

USW is trying to keep up with the changes in its membership and their needs. It is now partnering through the group, FOCUS, or Freelancers Organized for Change, Unity, and Strength to host virtual professional development events on topics such as livestream production and coding bootcamps in Pittsburgh.

In May, the group hosted a conversation on the PRO Act and its potential effects on independent workers. The proposed federal law – the Protecting the Right to Organize Act – would strengthen and protect the right to unionize, according to advocates, and passed the House of Representatives in March 2021. President Biden has come out in favor of the legislation that’s not yet been taken up by the U.S. Senate.

Uniting Under Common Workplace Needs

The people interviewed for this story work in different settings: at home, in a postpartum hospital unit, in a co-working space. They all agree that unions have something to offer workers.

For Padias, the issues of workplace equity cut across economic shifts. Tech workers, like those at HCL, experience some of the same issues that the coal and steel workers of Appalachia’s past dealt with.

“There’s no transparency in management decisions. There’s favoritism and a lack of pay equity,” she said. “These are the things workers can fix through a union.”

And she’s not surprised by the expansion of the United Steelworkers Union into emerging employment sectors outside its steel mill roots. Several hundred workers have joined USW since 2019. And Padias thinks that number will go up.

“We expect our new members will number in the thousands as rehiring happens, provided the pandemic eases,” she said.

Padias says that any group of workers in Pittsburgh should see the USW as a place where they can organize and assert their desires for fair wages and working conditions.

Laura Harbert Allen(she/her/hers) is a freelance writer, audio journalist and Ph.D. candidate at the Scripps College of Communication at Ohio University. She can be reached via lauraharbert.net or on Twitter @laurahallen.

This article was co-published with PublicSource, a nonprofit news outlet in Pittsburgh with a mission to inspire critical thinking and bold ideas through local journalism rooted in facts, diverse voices and the pursuit of transparency. Sign up for their newsletters here.