Sexual assault nurse examiners, or SANE nurses, are highly trained, specialized nurses stationed at hospitals across Appalachia to aid victims of sexual trauma.

These nurses don’t just collect rape kits, says Kate Martin, the lead investigative reporter for Carolina Public Press, but they conduct physical examinations that stand up to scrutiny in court, provide emergency medication for sexually transmitted diseases and HIV exposure, and emotional support for survivors.

When a SANE nurse is involved in a case, investigations are more successful and are more likely to result in a conviction.

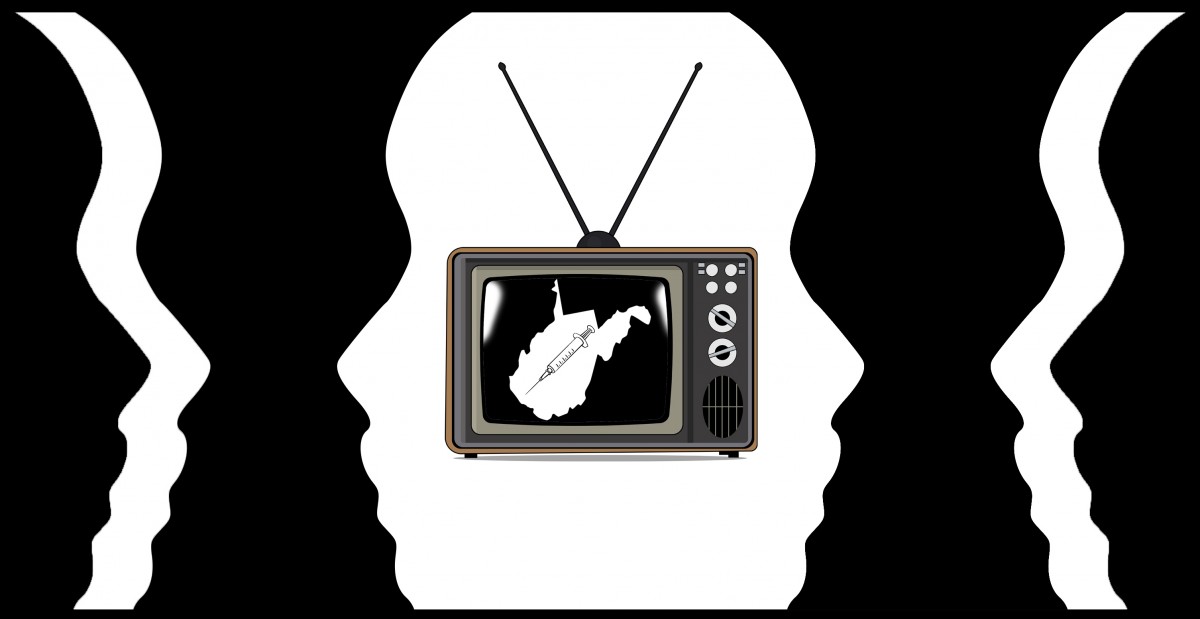

But in rural Appalachia, and in rural North Carolina more specifically, access to this highly specialized care isn’t guaranteed. In fact, North Carolina does not track how many SANE nurses are employed in the state or where they are located, and after years of struggling with the nation’s worst backlog of rape kits, Martin wanted to know what else the state was missing in assault survivors’ care.

Last month, Carolina Public Press released a two-part series investigating access to these highly specialized nurses in North Carolina. Martin spoke with 100 Days in Appalachia’s Ashton Marra about what her investigation found and what comes next in her coverage of sexual assault care in North Carolina.

***

Ashton Marra: Carolina Public Press has a history of reporting on access to health care services for sexual assault survivors in this state and also the recent backlogs of rape testing kits that North Carolina’s attorney general has really committed to reducing. Why is this topic something that CPP has dug so deeply into? Or if it’s more appropriate, why is this a topic that you felt compelled to dig into?

Katie Martin: Well, I think a lot of anecdotal information has come out in recent years regarding sexual assault. And, you know, if you’re assaulted, do you report to the police? Do you go to the hospital? And from there, does it get elevated to the district attorney? Every time you reach one of those steps, there’s people who fall off, there’s people who don’t report to the police. There’s people who don’t even go to the hospital.

For me, as a data reporter, I’m really interested in specifics. If I hear a statistic, I want to see some citations or the source for that, and in a lot of these cases, for [North Carolina] anyway, we had to find that information ourselves, because nobody was actually tracking it very well or at all.

AM: I want to specifically talk about the fact that no one is tracking access to services in the state, but first, can you define what a SANE nurse is? What does that mean? And what is the benefit for survivors to have access to this type of health care and support after an assault?

KM: A SANE nurse is a sexual assault nurse examiner. [This] is a nurse who has been licensed for at least two years, and then they go through an additional number of hours of training – they have classroom training that they have to complete and pass an exam. And then after that, they are certified.

[SANE nurses] do in-person exams of a person who’s been sexually assaulted. They learn all kinds of things like how to collect evidence from different parts of the body, what are the best methods to collect DNA, what you are not supposed to do when you’re collecting DNA, because you want to preserve the integrity of that evidence for trial if the survivor decides to go for that.

But it’s more than just the forensic part. I mean, everybody sees these TV shows where somebody gets assaulted, they go to the hospital, they go to a SANE nurse, and then after that, it’s all about putting the perpetrator on trial and everything. It’s a lot more than that [in real life].

This could be the first person you’ve seen since it happened. You’re telling them about the most intimate, traumatic thing that’s happened to you. You don’t know this person, most likely. They’re there to help you. They give you medication to prevent HIV and hepatitis from taking hold, if that’s a risk. They provide other medication for sexually transmitted infections, and they can also provide emergency contraception to prevent pregnancy. There’s also psychological needs that a person can have, there’s evidence of suicidal ideation after assaults and these specially trained nurses know the signs to look for. So, there’s a lot more that goes into it than just the forensic aspect.

AM: Is it fair to say it’s about providing holistic care for that person in that moment? They have more training that allows them to provide a holistic response?

KM: Yeah, it is. Any nurse that I’ve ever met, they care very deeply about people. But [SANE nurses] are trained to look for strangulation or signs of like abrasions on certain parts of your body. Are you trained to look for specific signs of strangulation or whatever as a regular nurse? Maybe not. That’s partly why they require SANE nurses to have at least two years on the job before even trying to take these courses.

AM: In your reporting, you set out to survey hospitals about access to these specially trained personnel. What did you generally find in your survey?

KM: We surveyed 130 hospitals and community programs [that provide similar services] and found, largely, urban areas have SANE nurses, and they have enough SANE nurses where you can show up at the hospital and you would run into one at any point. Now, that’s not to say that you would get to see a SANE nurse right away – there could be another survivor who is being seen by the same nurse on duty and you might have to wait for that exam to get done.

But if you’re in a rural area, it’s really hit or miss. There are some hospitals who have them. There are some who don’t. There are a few who did not respond to the survey at all and I’m seeing evidence that many of the ones that didn’t respond to the survey, they might not do assault exams at all, which is a future story that I’m working on.

AM: That rural/urban divide is something that inevitably in Appalachia always comes up when we talk about health care and it doesn’t really matter what kind of care it is, we see access kind of split apart on these rural/urban divide lines. So, when it comes to SANE nurses and the care they provide, what does that divide mean for people who live in rural communities? What does that mean for someone who is the survivor of a sexual assault, and then has to do what in order to get this specialty care?

KM: I will say that also in the survey, the rural hospitals often said that it’s very difficult to keep people because, you know, maybe the pay is not as good or they can’t afford to train the nurses. Imagine you’re in a rural area and you have to send one of your precious few nurses to get training in Raleigh, you have to pay for their travel, you have to pay for their hotel, their food, their training, and have to also account for all of that time off from the hospital and find somebody to fill their spot. So the hospitals in many rural areas are in a bind on this.

And as a survivor, you’re not going to know which hospital to go to [when you need this care], because who looks that up? Before you get assaulted, who would know that? So, what ends up happening is they go to the first hospital. That hospital might say, ‘Well, we don’t have a SANE nurse here, you need to go to this other hospital,’ and maybe they show up at the second hospital and maybe they do have a SANE nurse, but it’s Friday night and they don’t get back in until Monday. So then they go to the third hospital. I’ve heard cases where women have traveled to two or three hospitals and it’s taken 17 or 19 hours from the time they started looking for help.

And imagine also along the way, maybe you go to that first hospital and they say, ‘We don’t have a SANE nurse,’ and then you just say, ‘Oh,’ and go home because you’re in such a fragile state after such a traumatic event. I mean, that does happen. There are people who don’t get that help. And, again, a SANE nurse does a lot more than just the forensic aspect of it. I’m told about half of women who actually get a sexual assault kit, don’t actually report it to the police. They’re there for other reasons when a person needs help.

AM: You mentioned in your reporting that you actually had to conduct this survey of hospitals because there is no state level system for tracking where these nurses are located. Is that correct?

KM: That’s correct. We actually got the idea for doing this after talking to a SANE nurse. When we did our first series about [sexual assault] prosecutions in North Carolina, our data analysis showed that fewer than one in four people who are charged with a sexual assault are eventually convicted of sexual assault or a similar crime. And in talking with nurses for that series, they mentioned the SANE nurse shortage and told me I should look into it.

So I was like, ‘All right, let me just call the Department of Health and Human Services, surely they have a list?’ And they’re like, ‘No, you need to talk to the Board of Nursing,’ and the Board of Nursing didn’t have one. And then the State Attorney General’s Office didn’t have one. And there’s also the International Association of Forensic Nurses which certifies the SANE nurses, but the problem is their list is really out of date. They don’t track when people move to another hospital. So I was like, ‘Alright, I guess I’ll just have to ask all the hospitals how many nurses they have.’ And that’s how this series came about.

Deanne Gerdes, the executive eirector for Rape Crisis of Cumberland County, specifically spoke with me about Cape Fear Valley Hospital and their response to my survey where they said they didn’t have any SANE nurses. Two months after we received their response, on the eve of our publication of this story, they came back and said, ‘No, no, wait, we’ve got eight people in training.’ So, I’m not really sure what the disconnect was there, but, you know, it’s pretty clear that the Rape Crisis of Cumberland County organization, they could see on the ground that they didn’t have SANE nurses when they would go in to advocate for the survivors. So, something’s going on there.

AM: You are specifically reporting on North Carolina in this series, but is this a larger problem? Are there other states that are doing better at providing these services, or are other states or cities also struggling?

KM: I’m sad to say that most states in the country are in the same boat as North Carolina. There are a couple of states that are doing different things. Illinois, for instance, their legislature passed a law that said that hospitals have to have a SANE nurse by 2022. And my understanding is they’re all working on how to do that.

Massachusetts – which is obviously a much smaller state than North Carolina so they don’t have a lot of geographic issues like we do – they have 30 hospitals throughout the state that are on a map and you can look and see where the same nurses are located. They might not be on duty at that time, but there’s a map people can access, and then they also have a telephone line that’s open 24/7 where a nurse from a hospital that doesn’t have a SANE nurse on duty right at that minute can call and get help in doing their sexual assault exam. And in fact, that hotline service works with other rural areas, I believe it’s California, some military bases and also some Native American reservations.

AM: So there are some places that have found solutions to this problem to this kind of lack of access. Did it seem as if, when you were looking at solutions in your reporting, any of your sources thought those solutions might be viable for North Carolina?

KM: Oh, yeah. Some of my sources thought that the hotline idea was a really good one, because you don’t have to have a SANE nurse on duty. In rural hospitals where it’s so hard to keep after you get one anyway that could be a solution for the high turnover or, you know, just the lack of SANE nurses in a rural hospital.

It’s certainly not perfect. It’s best to have a SANE nurse in person, but that person on the phone might be like, ‘Alright, you need to look at her neck to see if she has bruises or swelling or something just in case she was being choked’ or listens to the survivor to hear what happened to her and then they say, ‘Okay, in my experience, you need to look for an abrasion on this part of her hip’ or something. That’s things that wouldn’t occur to a nurse who is dealing with a rural population.

Some hospitals have said they haven’t even seen a single sexual assault in a year, and that may be because people know that they can’t go there to get help.

AM: What are the benefits for having this type of care, in terms of both the healthcare aspect and the criminal justice aspect? What are the benefits that a community or city or state sees when they have comprehensive access to SANE nurse care?

KM: I talked to a prosecutor who works in the western part of the state. He prosecutes cases in seven counties, and what he told me is that the SANE nurses are indispensable. When you have a SANE nurse who has collected evidence from a survivor, that speaks to a level of credibility of training, of expertise. They often don’t even call the SANE nurse to testify in those trials because the defense attorneys know how reputable they are. So, that’s definitely a bonus for prosecuting people who are accused of rape.

When you have a SANE nurse, it helps the survivor psychologically. The evidence that I’ve seen from various studies shows that they’re more likely to talk to police after they’ve seen a SANE nurse as opposed to somebody who’s not certified with the same credential. They’re more likely to talk to police, they’re more likely to cooperate with investigations, they’re more likely to get a prosecution and the sentences are more likely to be longer. So from the criminal aspect, that’s very helpful.

You know, obviously, having an experienced nurse who knows about the different medications and the types of injuries that you have after an assault is highly valuable to a survivor’s peace of mind in such a tumultuous time.

AM: Where does your reporting go next?

KM: I am looking into various ways to determine which hospitals in North Carolina are not performing sexual assault kits. That indicates to me that they may be sending people to other places and that is a concern among advocates for sexual assault survivors, because, you know, when you send somebody somewhere else, they’re more likely to fall off than if they were to get help there. It could be increasing the spread of sexually transmitted infections for one thing, and there is psychological harm that happens when you don’t get help.

I will say that advocates are working with the state’s Healthcare Association, which said right after our report published that they are surveying hospitals throughout North Carolina to see how many SANE nurses they have. I hope that they will release that report. And this is sort of in preparation for state legislators looking at laws that can pass in North Carolina that will require hospitals to have coverage from SANE nurses in some fashion.

But I will say that advocates believe that it shouldn’t take a law. Deanne Gerdes from the rape crisis center of Fayetteville told me:

“Why aren’t these hospitals concerned about their survivors, their neighbors, their daughters, their mothers or grandmothers?”

She’s saying that it shouldn’t be about dollars and cents. A sexual assault nurse costs a lot of money, it takes multiple hours sometimes to complete these exams, and it’s the financial aspects shouldn’t necessarily be the top concern. They’re there to help people. They should provide the service for sexual assault survivors.

Kate Martin is the lead investigative reporter for Carolina Public Press. Her work has led to the resignation of several elected officials and the creation of several state laws in Washington and North Carolina. Her deep analysis of years of North Carolina court records showed that fewer than one in four people charged with sexual assault are eventually convicted of that or a lesser crime. She lives in central North Carolina and enjoys brewing beer with her husband.

Editor’s Note: This story initially misidentified a quote from Deanne Gerdes. It has been updated to reflect the correct attribution.