This month marks 40 years since the inception of a national celebration of women’s history. Approved by Congress in 1981 and first celebrated in 1982, Women’s History Month was initially designated as a week-long marker, recognizing the contributions of women to the nation.

Much like other designated month-long or week-long celebrations, the recognition of women is meant to highlight an often-overlooked portion of our country’s largely white male history. It is meant to show progress. But how far have we really come?

Appalachian women, in particular, have led the charge for change in our communities that have benefited our nation as a whole. Names like Mother Jones and Florence Reece come to mind, but also contemporaries like Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson and Ann Pancake.

The following is the story of one such woman, Georgia McIntire-Weaver, from Berkeley Springs, West Virginia. You’ve likely never heard of her, but she was a pioneer in the West Virginia legal system for women. Her story, based here on court records and newspaper accounts, is a tale of misogyny and perseverance, of a woman who may have made little progress in the moment, but created the momentum needed for future progress.

Georgia’s story below comes to us from contributor Justin McHenry.

— Ashton Marra, 100 Days in Appalachia

***

Berkeley Springs, West Virginia, 1922

Now hogwash, like pornography, is easier pointed out than defined. You know it when it gets thrown at you. A feeling when others are playing mental and emotional games for their own personal enjoyment. It piles up on your soul.

Often, historically and still yet today, it comes at the expense of women, so, year after year, it had mounded high for Georgia McIntire-Weaver, propelling her down the halls of the Morgan County Courthouse in Berkeley Springs on St. Valentine’s Day, 1922. A 17-page love letter folded in her hands.

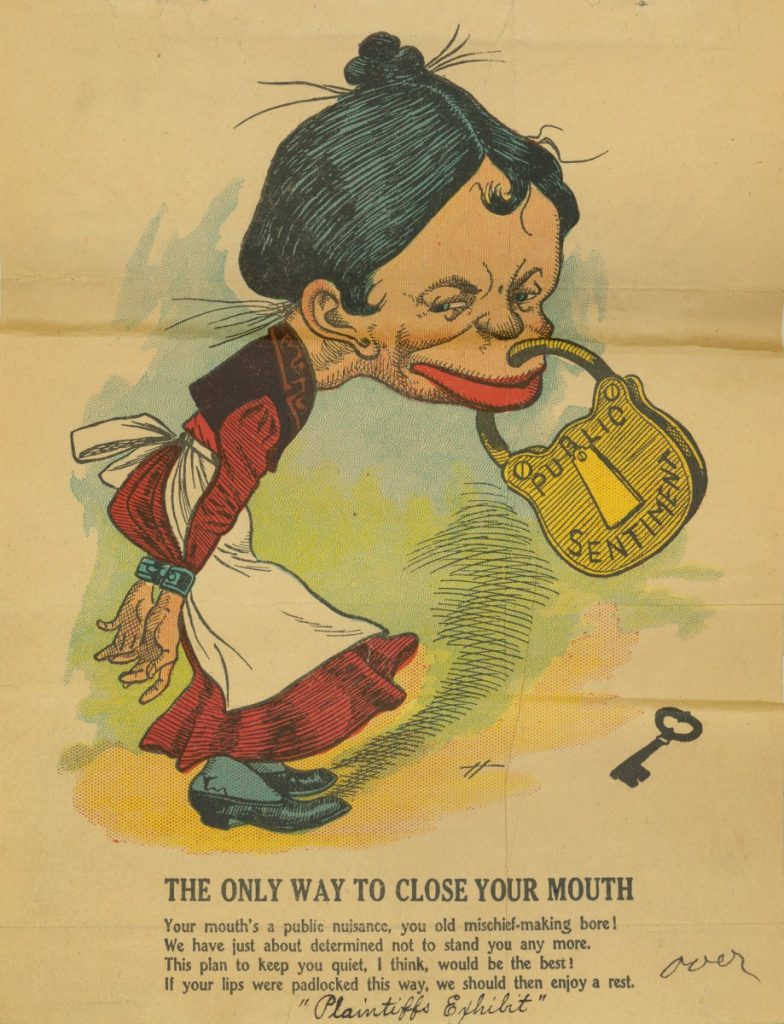

Past she walked by the Sheriff’s office whom she accused of belittling her all over town. Past she walked by the jailer whom she called an ignorant loafer. Past she walked by the mayor’s office who called her an old splattermouth. Past she walked by the bulletin board where they hung a sexist cartoon of her. Past the courtrooms where she was the first woman to stand at the bar.

Down those courthouse halls that she walked hundreds of times before. Prideful and defiant. She opened the door to the clerk’s office, handed over her valentine and walked out ready to take on them all, no matter what.

In 1922, Georgia McIntire-Weaver was 58. Those six decades being already filled with time spent as an actress, professor and the leading grower of watercress on the East Coast. She had been married to a bigamous scoundrel who had her thrown in jail after she discovered his secret life. What followed was law school in Atlanta and the start of her fight for women’s equality.

When she moved back to West Virginia in the winter of 1913, Georgia would rattle off a bunch of firsts for women in the state: first to pass the state bar exam, first to establish their own legal practice, first to argue a case before the state Supreme Court, and so on and so on.

As a lawyer and person, she did not care about disrupting the status quo. Time and time again she took cases that challenged the established authority structure championing for the people, all people, Black, white, interracial, women, workers and especially children. The general theme is she went above and beyond to represent these people at a time and place when many wouldn’t.

Georgia suffered no fools no matter who they were and for all of this – and primarily because she was a woman – she was singled out and targeted. Whether it was being indicted for browbeating a witness or fending off an embarrassed plaintiff storming into her office to accost her. Intimidation tactics used to put her in her place. To learn her how real women are supposed to act.

But she didn’t learn that lesson and kept on thumbing her nose at the haters and losers who were angry or jealous of her professional success. As a result of her not backing down, there began a systematic (alleged) campaign leveled against her by the mayor, jailor, deputy sheriff and sheriff to intimidate her and to intimidate her clients into dropping her, to get her disbarred and just general sexist behavior.

That love letter of hers in 1922 laid out the allegations against Berkeley Springs Mayor, John E. Helsley, N.H. Hobday and Sheriff A.B. Dyche – a filing for a lawsuit.

In the suit, Georgia claims Helsley and Hobday had been working together for about four or five years conspiring and colluding with one another against Georgia to destroy her career and run her out of town. When Dyche was elected Sheriff, he joined their little cabal.

Story after story tells how Hobday and Helsley would visit Georgia’s clients in their jail cells and bad-mouth her to them. They threatened one of her clients that if they didn’t plead guilty and drop her as their lawyer, there would be dire consequences. With another of her clients, they went one step further, arranging for another attorney to take her place. Tampering and intimidation tactics. It was an act they repeated, and it worked as Georgia began losing clients as a result.

Sheriff Dyche, for his part, would regularly complain to everyone while he was serving papers of hers saying that he was serving some more of that “old woman’s dirt.” He would also meddle in her affairs by talking to her clients to drop her.

During traffic court ruled over by Mayor Helsley, the two got into an argument and Helsley called Georgia “an old splattermouth” and looked to have her thrown out the door. She also claims that they called her “that old rip”, “the old hen” and “old huzzy.” Demeaning sexist name-calling.

But it was primarily Hobday who received the brunt of her scorn. She describes him thusly: “An ignorant, uneducated man, barely able to read, write and spell but after his election and appointment to the before-mentioned numerous offices [humane officer, jailor, deputy sheriff, constable], [Hobday] became obsessed with the idea of his own importance and seemed to think that some divine afflatus had breathed into his mind such legal knowledge that he held himself out as a legal luminary.”

Georgia goes on to write in her complaint that he likes to inject himself into legal proceedings and he runs his mouth off…a lot. Despite holding so many jobs and being paid by both the town and county, Hobday neglected his duties and spent the greater part of his time “loafing in the corridor of the courthouse,” according to Georgia. One of his favorite pastimes was standing out on the street in front of the courthouse complaining about Georgia and scheming ways to bring her down.

One such way was posting a “Comic Valentine” in the courthouse hallway. The “valentine” was a carton that depicted a less than flattering portrait of Georgia with her hands handcuffed behind her and a padlock clamped down on her lips, locking her mouth shut, with the phrase “public sentiment” written on the lock.

Georgia says that for a week this hung on a bulletin board at the courthouse with Hobday sitting under it to point it out to any and everyone who walked by and laugh. When she heard about it, she marched on down and ripped it off the board.

For years, Georgia kept up the fight but her case against the three men eventually was thrown out. Four years she fought the masculine hegemony of Berkeley Springs in court and demonstrated that she would not be denied.

Her lawsuits against the mayor and other town and county officials were early proto sexual discrimination and workplace discrimination lawsuits. To her, this was her fundamental right to the pursuit of happiness and that she as a woman enjoyed the same rights under the Constitution as her penised tormentors.

For her detractors, she wrote in a letter to the editor to the The News, “I have been made the target of a lot of roughnecks slandering and injuring me for the accomplishment of their own ends, and I shall test out the rights guaranteed me by the Constitution of the United States as well as of the State of West Virginia, as to my fundamental rights in the matter of ‘the pursuit of happiness,’ etc., for which rights our forefathers poured out their lives and their blood.”

It was not just one of those symbolic things which gain more meaning 100 years after the fact than they were perceived at the time. She was in it. Her blood. Her pound of flesh. A revolutionary ready to pour out her life just to be seen as equal.

Justin McHenry is an archivist, writer and historian from Charles Town, West Virginia, where he lives with his wife and two daughters.