Last Wednesday in Portsmouth, Ohio, a team of organizers with River Valley Organizing Project was out canvassing and encountered a man outside a corner store who was overdosing. The organizers were having folks fill out a survey—asking them what they love about their community, what they’d like to see changed, and if they had plans to vote.

They had been working for a while when they noticed the man outside the store, disoriented, his eyes were closing. Jenny Boyle, one of the canvassers, got the man to sit down and tore apart her truck looking for naloxone. Boyle says a woman driving by saw what was happening and passed her a dose out her car window. Boyle loaded up a syringe, but couldn’t find a good spot in his thigh because he was seated in an awkward position. So she plunged the needle into the fleshy area around his bicep.

Scared that the first dose wasn’t enough, Boyle readied a second. But then, suddenly, he woke up and was fine. “He hugged us,” she said, “and just bopped away.”

In the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States is experiencing an unprecedented spike in overdose deaths. In 2019, nearly 72,000 people died from an unintentional drug overdose, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention just announced that during the first three months of 2020, they predict an increase of 10 percent in overdose deaths over the same period a year before.

The policy and advocacy nonprofit Harm Reduction Ohio reports that at least 543 Ohioans died from a drug overdose in May–more than in any month in the state’s history. In a state that has been hit hard, Portsmouth’s Scioto County had the highest death rate for 2018 and 2019 and is on track to have the highest death rate this year.

The man that Boyle revived using naloxone was just the first overdose organizers from River Valley Organizing reversed last Wednesday. Before the day was over, they reversed one more in Portsmouth and two more in East Liverpool, Ohio.

Last Wednesday also marked a major milestone in the legal battle against the pharmaceutical industry over prescription opioids. The Department of Justice announced a plea agreement with Purdue Pharma for $8.3 billion in fines and damages.

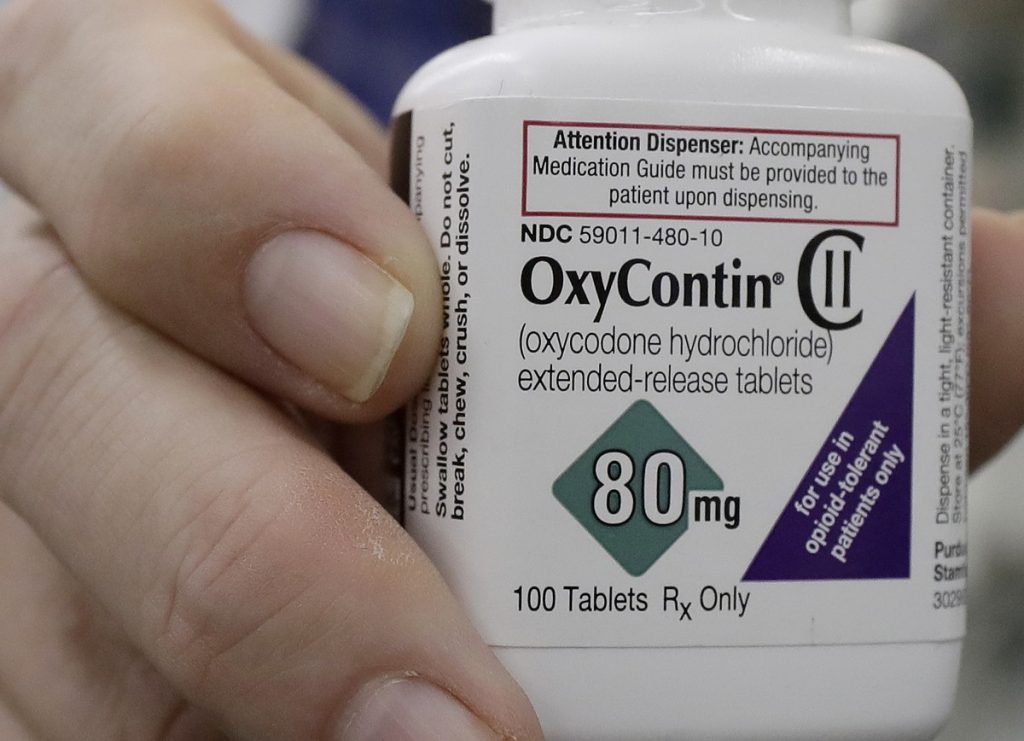

Purdue pled guilty to three federal charges including “defrauding the United States and violating the Anti-Kickback statute.” The company was accused of aggressively marketing their drugs to doctors as lower risk and less addictive than previous iterations of opioids. Their prescription pills were also being diverted to the illicit market, and they did little to stop it.

The company is bankrupt so if the deal is approved, Purdue will be dissolved and become a “public benefit company” with future sales being used to pay these debts. This new version of the company would continue to sell OxyContin as well as medication assisted treatment drugs.

The agreement, however, is separate from the ongoing cases in the Federal Court in Cleveland and in state courts—and there’s still the possibility of future criminal charges against individuals and executives, or the Sackler family for that matter, who were involved in Purdue’s crimes.

The Sackler family, the billionaires who profited off of OxyContin, will pay a meager fine of $225 million and give up their interests in the company. Through this agreement they’ll serve no prison time. In fact, they’ve managed to squirrel away more than $10 billion—in some ways they are the real winners here.

The Department of Justice announcement seemed to skirt the current overdose surge. Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey A. Rosen said in his remarks, “Today’s announcement focuses on the problems from wrongful activities in the prescription opioids realm, so let me note that our efforts there appear to be making a difference. The CDC reports that since 2017, prescription opioid overdose deaths have decreased–by over 18 percent in the first two years.”

Prescription opioids are not the central issue anymore. Most overdose deaths involve the synthetic opioid fentanyl and increasingly stimulants like methamphetamine and cocaine. The illicit drug supply is killing people— and the social isolation, anxiety and economic hardship brought on by the pandemic are making things worse.

Jenny Boyle said she hadn’t even heard about the settlement and was surprised when I told her the amount the settlement was for.

“That’s not even enough,” she said. “The money can’t bring back all those people. More and more people are being reversed by our naloxone, but the opioids are so strong now.”

For community organizers on the ground in Appalachia, their needs are immediate. They want greater support and lower barriers to access for harm reduction supplies—syringes, fentanyl testing strips and naloxone. Over the past few days, I’ve spoken with community-based harm reduction activists in Ohio and West Virginia who were mostly skeptical of the agreement and, to be honest, busy.

Last Wednesday, pastor Joshua Lawson from Wheelersburg, Ohio, just down the road from Portsmouth, was strategizing better ways to distribute naloxone in his community where he currently helps coordinate on-demand distribution out of a church. He’s working to get other faith communities involved, but is worried about funding, about sustainability, about what happens next.

Lawson said that for him the DOJ Agreement validates his work and the work of others somewhat. He’s hopeful that it could offer more funding for treatment and other resources to address overdose.

“Even if this settlement doesn’t come close to fully answering for the devastation that Purdue foisted upon so many of my friends and neighbors in Appalachia,” Lawson said, “it’s still better than nothing.”

Abby Spears, a Portsmouth native and harm reduction and policy coordinator for River Valley Organizing Project, began her day last Wednesday by sending out reminders about the county’s syringe program, and then she talked with a woman in a nearby county about a program there. Later she attended meetings where she’s trying to help re-think the laws that affect syringe programs. And in the evening she attended an online workshop for a possible grant. On top of all of this work, she’s working to open a drop-in center on Portsmouth’s East End.

Spears says she doesn’t know what to believe about the Purdue agreement. “Will it actually make it into the hands of the people and communities who were irrevocably changed by their product and policies?” She’s not holding her breath she says, “because this country has a long history of protecting profit and wealth over the people harmed.”

Portsmouth has been hard hit by the overdose crisis. This small Appalachian city on the banks of the Ohio River has had its share of economic struggles over the past few decades – from losing steel mills to being set upon by Big Pharma reps who flooded the region with opioid painkillers. In 2010 alone, at least 9.7 million doses of opiates were dispensed in Portsmouth’s Scioto County—123 doses each for every person in the community, child and adult alike, more than any other county in Ohio.

The community helped shut down the so-called pill-mills, but the unintended consequences were heightened rates of intravenous drug use. The local health department started a syringe exchange and promoted harm reduction practices like naloxone distribution.

But stigma hinders some harm reduction efforts—it’s that same stigma that also prevents people from getting help with addiction. Some people still think that addiction is a moral failing. People often use drugs because drugs make them feel better. The next question should be, why do people feel bad?

Indeed, it would be easy to blame Big Pharma for its role in what happened in Appalachia, but that wouldn’t completely explain why so many people are overdosing now on stronger, illicit forms of opioids, nor would it explain how opioids caught on so quickly in the first place, or why they continue to appeal to people in the United States, or why opioid use disorder is a thing. It’s not the drug itself—most people who use opioids will not become addicted. For many people, the pain relief from opioids can be life-changing and life-improving.

We can’t address overdose—and really all so-called deaths of despair— if we don’t address economic conditions in Appalachia. The research is clear that the most poor and marginalized in our communities are the most vulnerable to overdose and are also the most susceptible to substance use disorder.

Big Pharma acted like most companies have in Appalachia: They want timber. They take it. They want coal. They take that. Each time industry extracts and leaves without having to address the outcomes—that becomes the problem of those living there. The pills were no different.

In a recent Facebook Live event, a Portsmouth-based River Valley Organizing Project member named O.G. Menace, who was also out canvassing last Wednesday, said he knows how he’s going to address the overdose crisis. He’s hitting the streets and handing out naloxone.

“The way things are heading and the way things are,” O.G. Menace said, “it’s here now and we’re dealing with it. And we’re going to continue to deal with it.”

Jack Shuler is the author of four books, including This is Ohio: The Overdose Crisis and the Front Lines of a New America. He recently edited with Michael Croley Midland: Reports from Flyover Country. His work has appeared in The New Republic, The Christian Science Monitor, Salon, among others. He chairs the narrative journalism program at Denison University.