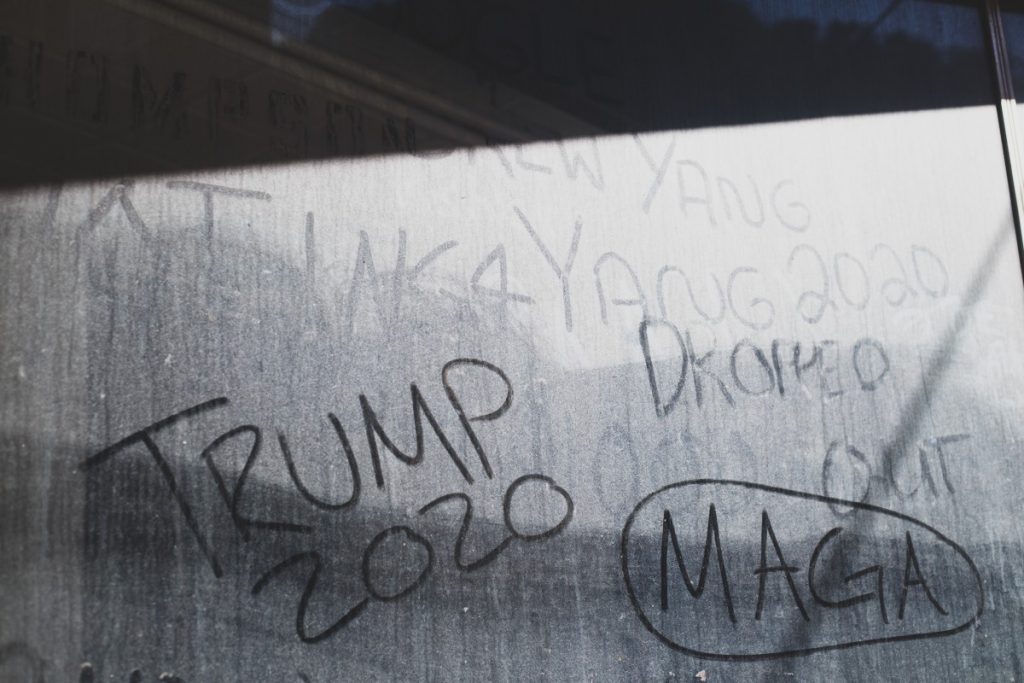

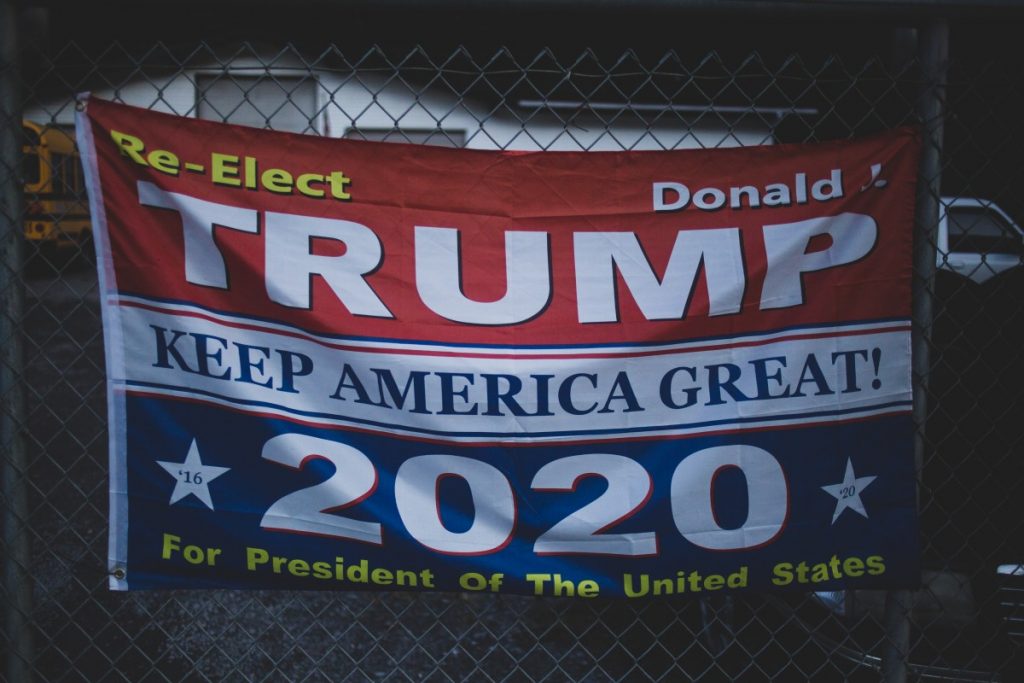

You don’t have to go far to find evidence of support for Donald Trump’s re-election to the presidency in southern West Virginia. “Trump 2020” signs dot yards and interstate exit ramps, hang from front porches and are posted on the sides of barns and sheds.

In late August, a boat parade on the Kanawha River in Charleston drew hundreds of watercraft, Trump 2020 flags streaming from the wakes of pontoons, fishing boats and dinghies alike. Several boats docked at Haddad Riverfront Park near downtown, where onshore spectators cheered and waved flags themselves as drivers honked horns to show their support.

It was an enthusiastic if less crowded event than then-candidate Trump’s campaign rally in West Virginia’s capital city in May of 2016. Speaking to a boisterous crowd of around 12,000 supporters at the Charleston Civic Center – many of whom held “Trump Digs Coal” signs – Trump promised to save the ailing industry. “We’re gonna take care of a lot of years of horrible abuse,” he said. “I love the miners and I love what they do.”

It was a mainstay in the 2016 election cycle: Trump was going to save coal.

And an unforced error from Hillary Clinton helped him make the case. Clinton’s comment about putting “lots of coal miners and coal companies out of business” during a CNN Town Hall in March of 2016 were perceived as a threat to the survival of coal communities.

A few months later, protestors greeted Clinton when she visited Williamson, West Virginia, offering some clarity to the remarks taken out of context in hundreds of attack ads. Although she apologized and promised to support coal miners if elected president, the damage was done. Sixty-eight and a half percent of West Virginia voters who went to the polls marked their ballots for Donald Trump in 2016.

Some four years on, the Trump administration has delivered on some of those promises. Notably, President Obama’s 2015 Clean Power Plan (CPP) has been eradicated. The plan called for a reduction of carbon dioxide emissions from power generation to 32 percent below 2005 levels by 2030.

In August, the Environmental Protection Agency announced they were scaling back even more Obama-era regulations, allowing coal-fired power plants to dispose of wastewater containing contaminants like lead, selenium and arsenic into waterways. EPA administrator and former coal lobbyist Andrew Wheeler told the New York Times the move would “reduce pollution and save jobs at the same time.”

Profits in the industry appear to have rebounded, but the jobs have not come roaring back during Trump’s presidency as he promised. Coal jobs in the United States have hovered around the 50,000 mark for the past three years, before plummeting to less than 42,000 jobs in April due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Mining jobs have since ticked upward, to just over 45,000 in August nationwide.

And the coal industry came into the pandemic in a weakened state to begin with. Cheap access to natural gas has provided a cleaner alternative to coal, and the renewable energy sector is growing. Within 30 years, only about 13 percent of the nation’s electricity will come from coal, according to a report from the Energy Information Administration, compared to 25 percent today. Collectively, renewable sources and natural gas will provide about three-quarters of the nation’s electricity by mid-century, according to the EIA report.

Perhaps that is why there is not much talk about saving miner’s jobs from the Trump campaign in 2020: There simply isn’t good news to share when it comes to the future of coal in central Appalachia – or anywhere else, for that matter.

Barry Tadlock, a professor at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, whose research interests include Appalachian politics, thinks that there are several reasons that coal mining and coal miners are missing from the political discourse of the current campaign cycle. “The enormity of everything else that’s going on — COVID, race relations, climate change, economic challenges — is a contributing factor to relatively less discussion of coal,” he said.

Tadlock also said that the Trump campaign likely believes that the industry – and the people who work in it as well as support it – is solidly in its back pocket, so there’s no need to spend time or money during a highly competitive election cycle cultivating further support, especially while the President appears to be vulnerable with other electoral demographics.

“I have a hunch that the campaign feels a need to concentrate its resources in other areas and with other demographics that they’re less confident in, in terms of support,” Tadlock said.

For example, Trump’s perceived edge with white women voters appears to have softened this election cycle in key battleground states like Wisconsin, where Trump won white women by 16 percent in 2016. This year, he’s down 9 percent in the state according to a recent ABC/Washington Post poll.

But Trump still enjoys strong support in central Appalachia for reasons that run deeper than his fiery pro-coal stump speeches during the last presidential campaign.

“The coal companies set the tone for what folks believe. And the companies remain pro-Trump,” said Wilma Steele, a founding member of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in Matewan.

So, while the industry isn’t heralding the resurgence of coal jobs this election cycle, traces of implicit pro-Trump support remain.

An example is the website for the West Virginia Coal Association, an industry trade group whose members include executives from coal companies with mining operations in the state. As of publication, the landing page of the WVCA website still led with a story from October of 2017 that states: “Our mines are once again producing,” and that “we are beginning to rehire miners after 8 long, hard years of fighting to just stay in business.”

While the WVCA isn’t praising President Trump for saving the industry, the presence of a three-year-old post on its homepage illustrates Steele’s point.

“If the companies don’t complain about the president, the people won’t,” she said.

________

Upstream along the Tug River from Steele in Matewan sits Welch, West Virginia, the seat of McDowell County. People there have no illusions when it comes to the coal industry’s viability.

“The folks of McDowell County do not think the Glory Days will return,” said Rev. Olen Butcher.

Butcher is the pastor for First United Methodist Church in Welch, a town once described as “Little New York.” McDowell County was the number one coal producing county in the United States for years, with over 100,000 residents in the early 1950s. 2019 population estimates placed the population near 18,000.

As Butcher noted, times have changed and people in his community know it. When it comes to support for the President, however, coal’s decline doesn’t matter.

“Coal is not just a fossil fuel,” Butcher said. “Coal is a heritage, a way of life, a culture. Speaking of coal as a dispensable evil that needs to be snuffed out is like telling someone their grandmother was a woman of questionable character.”

Butcher, who grew up in southern West Virginia, said experts overlook the way coal is woven into the social fabric of communities like Welch. The dismissive attitude many saw in Clinton’s remarks is one example. “[Trump’s] base is simply satisfied to have a voice that will say what they are thinking,” Butcher said.

The reason that Trump and organizations such the West Virginia Coal Association are successful may be because their rhetoric appears to be supportive of the culture and heritage of coal community residents. Steele points out that organizations like “Friends of Coal,” founded by the WVCA in 2003, have stepped into the void left by the demise of unions in central Appalachia.

In 2019, about 6,600 miners belonged to the United Mine Workers of America out of a total workforce of about 30,000 surface and underground miners. Meanwhile, Friends of Coal stickers and license plates create a sense of shared community that is supported by state government leaders as well.

Some in central Appalachia believe that support for Trump is even stronger than it was four years ago.

“I think that it’s grown by leaps and bounds,” said Andy Bryant, who lives and works near Charleston.

Bryant is the son of a Union miner who helped get Cecil Roberts elected as UMWA President in the late 1970s. He believes that the recent Black Lives Matter demonstrations sparked by the killing of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by police in the U.S. have increased support for the President in his community.

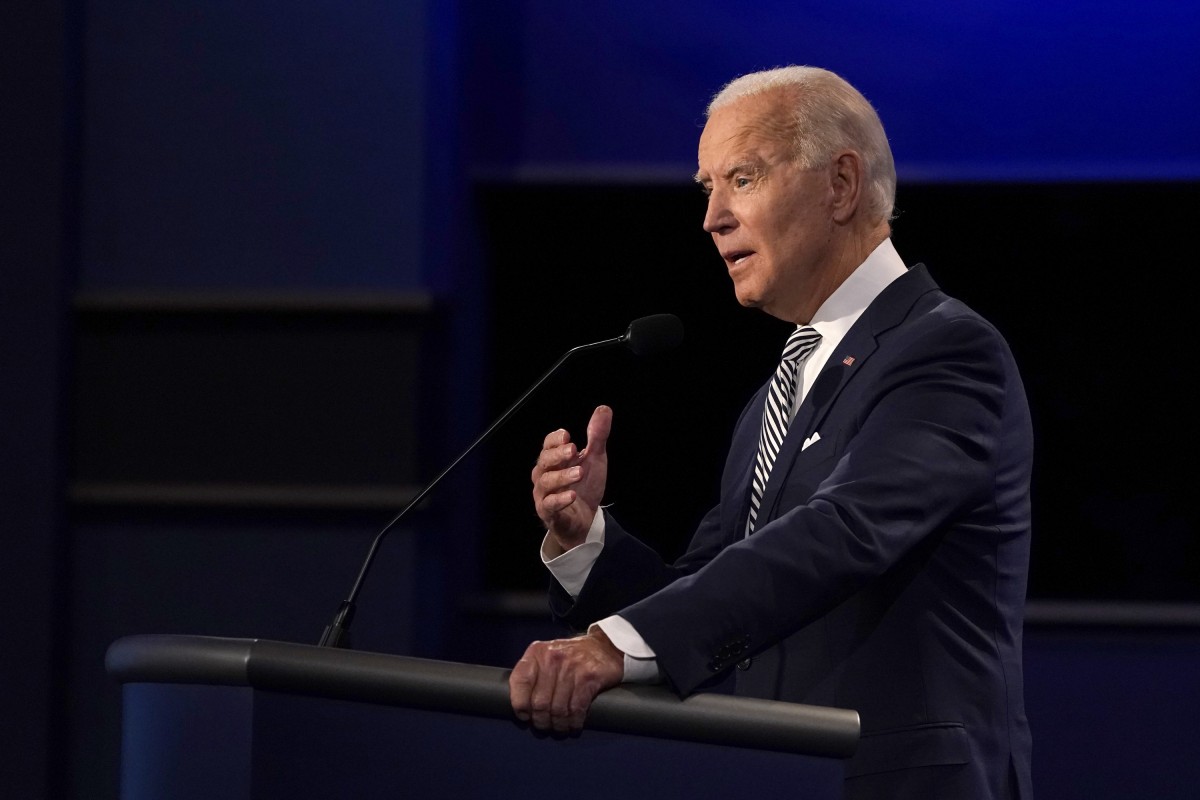

“Once our televisions started showing the rioting and burning down of downtowns and in some cases minority owned businesses, I think some changed their minds,” Bryant said. Social unrest has pushed conservative-leaning voters who might have considered voting for Joe Biden to support President Trump.

_______

In the aftermath of the 2016 election, central Appalachian communities like Welch and Matewan came to represent the angry working class white male voter responsible for Donald Trump’s election. Perhaps now, there are clues – breadcrumbs, if you will – that point to a place beyond the polarization and us-versus-them rhetoric that has dominated Appalachia and the nation. There is, after all, plenty of history in the region that shows it’s possible.

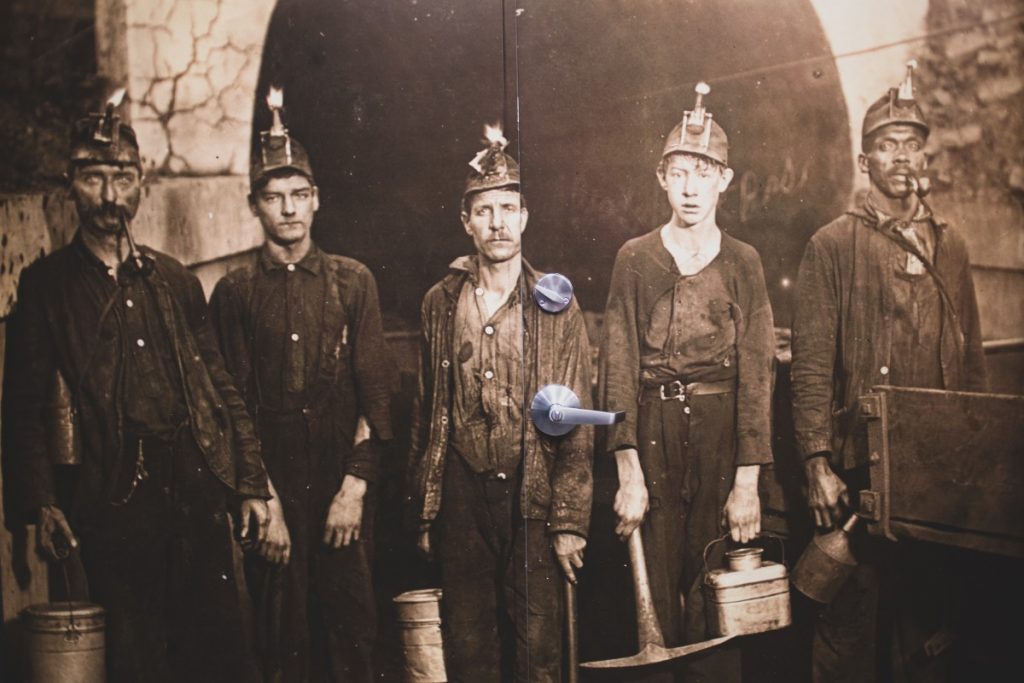

In the 1920s, Black, immigrant and white coal miners overcame the racial prejudice that was encouraged and reinforced by systems set up by coal companies. Practices included segregating neighborhoods and schools and paying Black coal miners less than their white counterparts. Miners collectively rose above these practices and came together to demand better pay and working conditions, culminating in the Battle of Blair Mountain. One miner who fought in the battle called it: “A darn solid mass of different colors and tribes, blended together, woven together, bound, interlocked, tongued and grooved together in one body.”

In Matewan today, Steele said there are glints of hope that this sense of community is returning. “In tiny towns across West Virginia, something is happening,” she said. “People are coming together for the survival of their communities.” She cites the Mine Wars Museum as one such example.

Across the street from the museum, Steele said a family with strong ties to the coal industry owns and operates a small business. Despite significant political differences with Steele, the business owner worked with her to lead and sponsor an event that resulted in the removal of more than 1,000 tires from the Tug River.

“We will look at each other’s Facebook wall and disagree, but we talk about the good stuff too,” said Steele. “We can leave the politics alone to do the work.”

Upriver in Welch, Butcher noted that floods often carry away tires that eventually wind their way down the Tug to Matewan. He believes it’s an example, theologically speaking, of redemption at work.

“It means that you get back on your feet, that you get another chance,” he said. “The river takes all the trash, and folks in Matewan clean the river.” It’s about recognizing that human dignity can unite people across ideological differences, he said, sometimes without them knowing it.

In towns formerly dominated by the coal industry, these quiet examples of perseverance and persistence show that there is community beyond the political polarities of the past four years. Perhaps that holds lessons for the future of Appalachia, and America as well.