Spring, summer and fall in Gilbert, West Virginia, in Mingo County, most days you can find a barrage of ATVs rolling through town.

Most of the riders are visiting for an adventurous vacation. The asphalt road runs are usually a short trip from their cabins, or hotels to the woods onto the Hatfield and McCoy Trail systems.

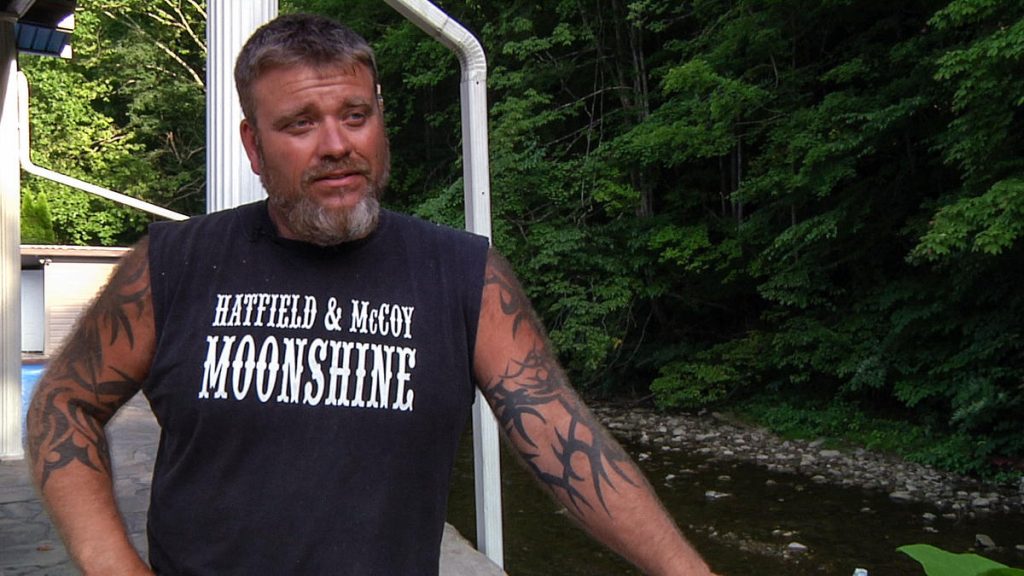

Chad Bishop is the master distiller in a nearby distillery.

“You come down here at any given time and you’ll see twenty four-wheelers over here, five over there six, ya know,” Chad said. “Those people come in here to spend their money.”

To get there, you have to drive up a steep hillside to get to the Hatfield and McCoy Distillery. Most of the customers are ATV tourists.

“When they come up my distillery if they want a bottle of my product they’re getting the best money can buy,” Chad said.

Chad takes a lot of pride in making moonshine. Technically it’s whiskey according to the Alcohol and Beverage Commission, but for Chad, the craft of brewing corn mash will always be moonshine. Chad said the recipe comes from the infamous William Anderson “Devil Anse” Hatfield himself.

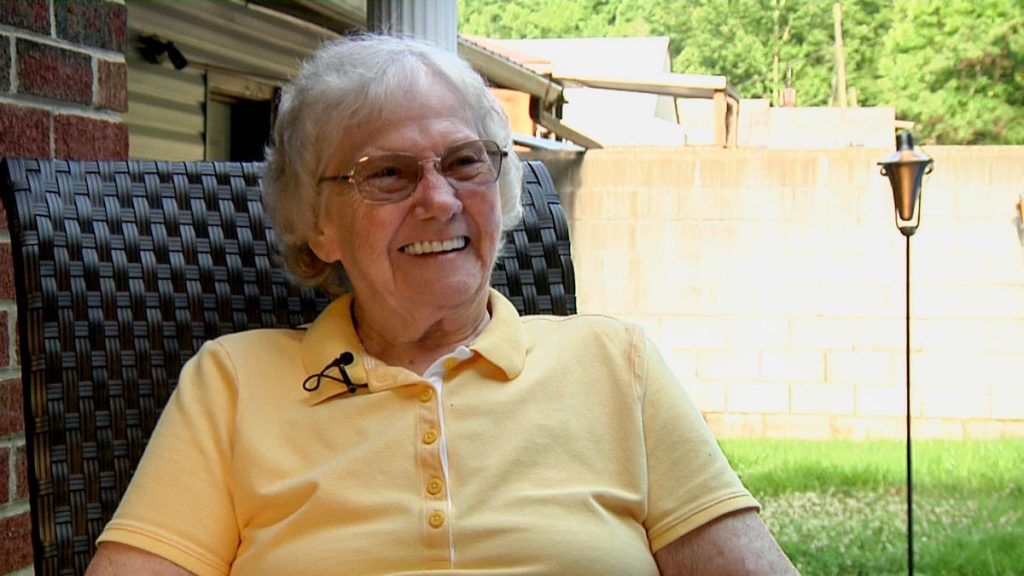

Chad married into the family. His mother-in-law is Nancy Justus, the great, great-granddaughter of “Devil Anse”.

Nancy’s father worked in the coal mines. But the boom and bust cycle meant he was often out of work.

“Everybody was poor. We didn’t know no better,” Nancy explained. “He had a tough life. Coal mining’s hard. It’s a hard life. We would have starved to death if it hadn’t been for bootlegging back in the 50s.”

Her daddy made moonshine with a radiator. She said today, it would take a lot longer if they had to make moonshine that way.

But the moonshine tradition goes back even before the 50s, according to Nancy’s mom, Billie Hatfield; often people call her ‘Granny Hatfield’.

“Back when I was 20 years old, we got married and we moved to Ben Creek a little hole in the ground; one way in one way out,” Granny Hatfield said. “To make extra money, we made moonshine and sold it. We hid it when he’d bring it out of the mountains, I would mix it in a bathtub. And I got pretty good on my 90 proof and all of that. Back then we made 90 proof and 100 proof. You had to watch the feds all of the time because they were all the time after us.”

Today, the family business is legit, a registered, tax-paying business that helps them make a living and stay in West Virginia.

In addition to the distillery, Nancy Justus also runs a small lodging company that rents vacation cabins and hotel rooms to tourists. She doesn’t mind sharing her family’s story with visitors.

“I enjoy talking to them,” Nancy said. “I talk to so many people, take so many pictures. I’m not famous or anything, but they always a picture.”

Nancy said she feels like she’s reclaiming her family’s name through her businesses, and by telling these stories. Even though the family wasn’t consulted before construction of the trail system that uses their name, both Chad and Nancy said the Hatfield and McCoy Trail system has been great for business.

Still, running a business that depends on tourists isn’t profitable year-round.

“There’s only seven months of business,” Nancy said. “It’s dead for five months and it’s hard to come back when you come back in March, first of April, because you had to spend all your money for the winter. That’s the only downfall, you know. It’s so hard.”

Just recently, Nancy’s moonshine company won a long battle with producers in other states, including Missouri and California, who were trying to use the name for their own brands of liquor.

“I got what I wanted. I want my name,” Nancy said. “I don’t want anybody to have my name that’s not the real people. It’s not fair.”

Nancy and her company won the lawsuit. Now they get to keep the name, Hatfield and McCoy Moonshine, to label their liquor. Chad said it’s good for tourism too. Along with the Hatfield and McCoy Country Museum in Williamson, it’s just one more way to bring another layer of authentic heritage to share with visitors.

“You can come here and go to a museum, and you can come here and watch whiskey being made the mountains you know, just like they did 150 years ago,” Chad said. “So yeah. I mean, they use the name but I think if anybody’s got the right to use it, it should be them.”

After all, the craft and recipe for this liquor were developed and preserved in the backwoods of the West Virginia hills. So the only way for it to be authentic is to keep the name.

“We don’t really play off of the name but we want what we want people to know is here we stick true to tradition,” Chad said. “We’re from the mountains, we make whiskey in the mountains. We do it all in the mountains.”

Reclaiming their name for their business is also about taking back the narrative that has been told over the years, said Nancy. Ever since the feud, reports have traditionally focused on the fights and anger among the families.

“I could write a book on our family,” Nancy said. “It was Hatfields. The curse was handed down there’s a lot of temperament. They have a lot of problems with forgiving. They can’t forgive. It’s sad.”

While she admits that most of her family members have a bit of a temper, she’s quick to point out that there’s more to her family.

“Hatfields are great people. My daddy would have given you the shirt off his back. I loved my daddy,” Nancy said.

“I was his sidekick and anything he told me to do, I’d do it. And there was things I did that I probably shouldn’t have done. I should have been killed. He bought me race cars. I raced them. What was I going to do with Corvettes? I raced them. Camaroes. Daddy taught me all of that.”

This story is part of an episode of Inside Appalachia that explores tourism in southern West Virginia and the lasting impacts the Hatfield and McCoy feud has had on the region’s identity. It was originally published by West Virginia Public Broadcasting.