This article was originally published by Carolina Public Press. Carolina Public Press is an independent, in-depth and investigative nonprofit news service for North Carolina.

North Carolina is No. 1 in an ignoble measure: As of last year, it had the most untested rape kits in the entire nation.

Hundreds of police departments, hospitals and universities statewide had stockpiled 15,130 kits, according to a tally released last year.

Nationwide, grants have helped pay to test thousands of kits sitting on shelves. The evidence contained within has led to thousands of new DNA matches in the FBI’s nationwide genetic profile database called CODIS, according to The New York Times.

Testing kits in North Carolina has helped secure convictions in old cases.

Statewide, roughly 16 percent of those charged with rape are convicted of rape, according to a Carolina Public Press analysis of state court records.

A bipartisan proposed state law winding its way through the N.C. General Assembly aims to eliminate the backlog. Called the Survivor Act, it seeks to provide $6 million to test older rape kits and create a policy to ensure sexual assault evidence kits never build up again.

The proposed law change was unveiled at a January press conference by state Attorney General Josh Stein. The bill’s main sponsors are Sen. Warren Daniel, R-Burke, and Reps. James Boles Jr., R-Moore, Carson Smith, R-Pender, Mary Belk, D-Mecklenburg, and William Richardson, D-Cumberland.

“We need to improve the criminal justice system so more rapists are arrested and put behind bars,” said state Attorney General Josh Stein late last month. “It’s critically important to the victim to know that there’s justice, and it’s also to the benefit of the community.”

The legislature required the kit count in early 2017. Before the count was completed, Stein said he had figured there might be a few thousand kits in the entire state. When Stein saw the results of the rape kit tally at the end of 2017, he was shocked, he said.

“To realize there were 15,000 untested kits … was like being hit in the face with cold water,” Stein said.

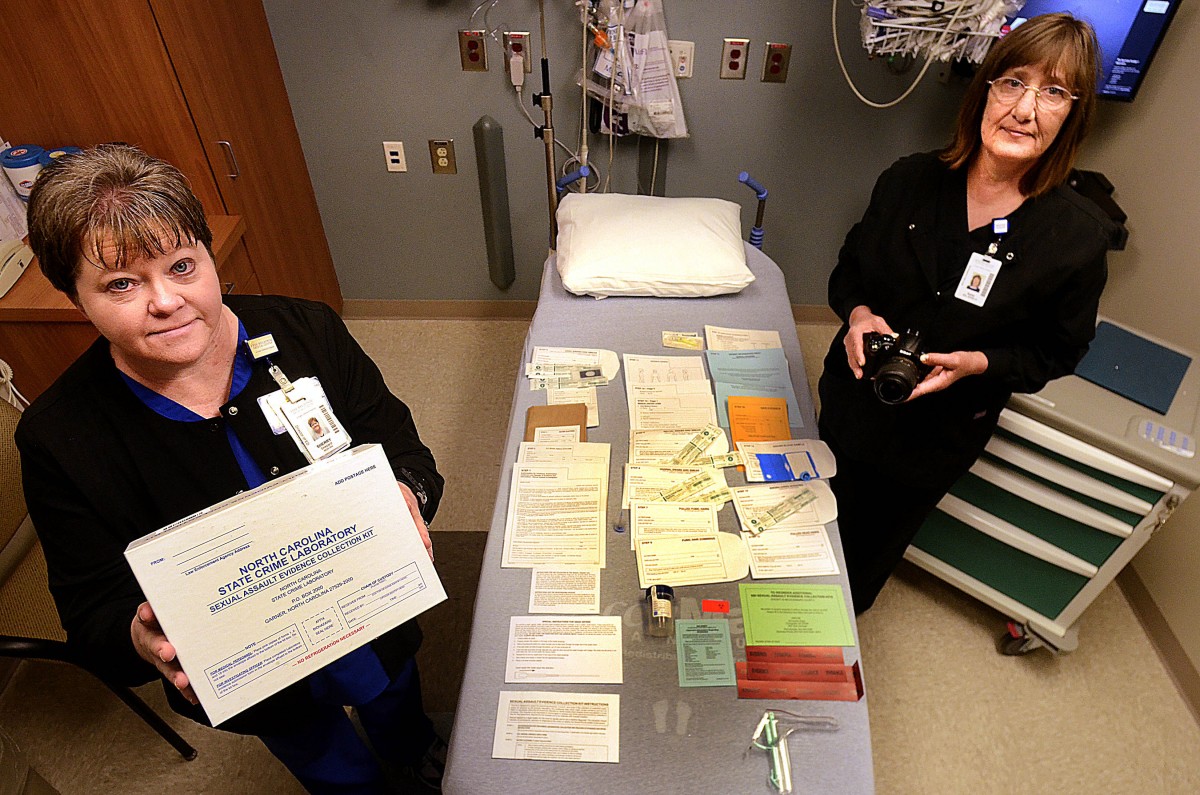

Each kit represents a victim, a violation, and perhaps the key to justice — if only it were tested for DNA evidence. It can take from four to five hours, and sometimes up to eight hours, for a nurse to perform a forensic exam.

It can take an hour or more for rural victims to find a hospital with a sexual assault nurse examiner, or SANE nurse, who is specially certified to collect the evidence now present on the victim’s body. If the SANE nurse is not on shift yet, the victim may spend many more hours waiting.

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking. Experts say DNA evidence ideally should be collected within 72 hours to be analyzed by a crime lab.

After driving to the right hospital and waiting, the victim must endure the invasive exam, which can take many more hours as a nurse thoroughly examines the body looking for traces of evidence that could be used to put the rapist in jail.

For now, it’s up to each agency to decide how it handles kits — that is part of the reason why rape kits built up in the first place, said Lt. John Somerindyke, head of the Fayetteville Police Department’s special victims unit.

“DNA technology has significantly increased,” he said of the decades since he started his career.

In the last couple of years, some departments around the state have received grant funding to test some of the kits in their backlogs. So far, testing produces results.

Of more than 800 kits recently tested from the Winston-Salem Police Department, the DNA matched 87 people whose genetic material was in the federal CODIS database, Stein said.

“We can solve about 10 percent of these cases if we just do the work,” Stein said. As more kits are tested, “the more connections there will be to known individuals on the database, which will lead to arrest.”

The Albemarle Police Department in Stanly County had 55 of the state’s untested kits last year. For its population, the Charlotte-area county charges more people with rape per capita than the state average.

It’s been testing some of its old kits lately, said Assistant Police Chief Jesse Huneycutt.

“We actually had a hit on a case just recently that I worked on, it was probably 16 years plus, that we actually got a hit on that case from an old rape kit that was submitted,” Huneycutt said. “Those type of things you like to see come full circle in the end.”

In December, Winston-Salem police submitted a nearly 30-year-old kit for analysis. Investigators said they linked the DNA, collected in 1990 after a stranger rape, to a Winston-Salem man. Police arrested the alleged perpetrator in February.

In November, Fayetteville police arrested a man in connection with a 2001 rape after sending an untested kit for DNA testing.

The Survivor Act mandates a uniform process for testing rape kits for all agencies to follow:

- Any agency that collects a rape kit must notify law enforcement within 24 hours.

- Police have 45 days to conduct a preliminary investigation.

- Kits must be then sent to a lab for DNA testing and a possible match with the FBI CODIS database.

The bulk of the $6 million in the Survivor Act would pay to test old kits in the next two years. Of that amount, $800,000 will pay for more forensic scientists at the state crime lab to address the increased workload.

The number of untested rape kits now remains unclear, though Stein said in January it was more than 10,000. Money from a separate grant will pay for two people to travel around the state to get an updated count of the kits, Stein said recently.

Since the Fayetteville Police Department started testing what once was a backlog of more than 600 untested kits, police have arrested 37 people, Somerindyke said.

As of January, the department’s backlog has been reduced to zero. Over the past two years, the department has sent batches of a few dozen kits to an outside forensics lab. Grant funding pays for the testing.

The oldest kits in Fayetteville were from 1984. Even decades later, the DNA in the kits can help police find suspects.

“We recently just made an arrest in an unsolved 1987 stranger rape,” Somerindyke said. “I don’t know if (DNA testing) was even an option then. Years go by and cases pile up.”

Meanwhile, unidentified rapists remain free.

“I will stand by this statement: All rapists are serial rapists,” Somerindyke said. “The bottom line is all rapists need to go to prison.”

This article was originally published by Carolina Public Press. Carolina Public Press is an independent, in-depth and investigative nonprofit news service for North Carolina.

Contact Kate Martin, lead investigative reporter at Carolina Public Press, at [email protected]. Contact Imari Scarbrough, contributing reporter at Carolina Public Press, at [email protected].

Illustration by Mariano Santillan of Carolina Public Press.