Grant Oakley’s second day of work was the last day of his life.

Seventeen, sandy-haired and tall, Grant liked to fish, tinker with motorcycles with his father, Mike, and play tuba in the school marching band. He was excited in the fall of 2015 when he landed his first part-time job at a farm supply business. The location was convenient; Bluegrass Agricultural Distributors was just across the highway from the Oakley family’s farmhouse near Lancaster, Kentucky, in rural Garrard County.

This April, Pam Oakley walked across the yard and pointed at the front porch. “Week before this happened, we sat on that porch and took his senior pictures,” she said. “He never got to see ‘em.”

Pam and Mike Oakley avoid the front porch now. The view of the now-empty storage sheds and silos at Bluegrass Agricultural is a constant, painful reminder of the accident that took their son’s life. Until recently, they didn’t even cross the street.

Grant worked a few hours after school on a Monday. But he was looking forward to his first full day of work the next day, Election Day, when he had the day off school.

The owner told state investigators he liked to let his employees leave to vote, and Grant — not old enough to vote yet himself — would be covering for them.

According to a state investigation, shortly before closing time on November 3rd, a 19-year-old forklift operator was returning the equipment to the main facility for storage. Exactly what happened next is not clear.

“The victim had hitched a ride on the forklift,” an inspector with Kentucky Occupational Safety and Health concluded in his report. The operator’s manual for the 6-ton forklift, with front tires nearly four feet tall, clearly prohibits passengers.

As the forklift approached a gate, Grant either fell or hopped down from the forklift. Somehow, he ended up underneath it, and the forklift’s rear wheel ran over his chest and neck.

The operator shouted for help. Mike Oakley recalled that another employee ran to the house to find him.

“They said ‘Grant’s hurt,’” he remembered. “I took off running.”

Mike and Pam arrived just before a medical helicopter flew Grant to a hospital.

“He was in so much pain,” Mike said through tears.

Grant died that evening.

The Oakleys had so many questions: Why was Grant allowed to ride on the side of the forklift? How fast was it going? Who saw what had happened?

Stunned, bereaved, the Oakleys looked to the Kentucky Occupational Safety and Health office, or KY OSH, for answers. In Kentucky, KY OSH is the state agency that has primary responsibility for enforcement of work safety regulations, including investigations of workplace accidents, injuries and fatalities.

But the Oakleys found the investigator’s handwritten notes incomplete and hard to read. It appeared the state’s inspector didn’t question witnesses.

“They closed his case so fast,” Mike Oakley said.

“And they said it was not necessary for them to talk to all the witnesses,” Pam Oakley added. “Who doesn’t talk to the witnesses? When somebody dies, who won’t talk to the witnesses?”

Since then, a county prosecutor and federal labor officials have reviewed the KY OSH investigation of Grant’s death and confirmed what the Oakleys suspected: the work was sloppy, incomplete, and not in compliance with the federal requirements.

The prosecutor says the failings hindered his attempt to build a criminal case. Mike and Pam Oakley say their family has been left with years of lingering questions, compounding their grief.

Criminal Charges Considered

When Andy Sims learned of Grant’s death, Sims thought there might be grounds for criminal charges against either the company management or the equipment operator.

“Any time someone dies, I want to look into it,” said Sims, the Commonwealth Attorney for Kentucky’s 13th Judicial Circuit, which includes Garrard County.

Sims turned to the KY OSH investigation to learn more about the circumstances of Grant’s death.

But instead of a willingness to help him build a case, Sims said he found an “extremely frustrating” lack of cooperation from the agency officials. And when he finally did get the materials, Sims said, he was disappointed by the lack of substance.

“There were few photographs of the scene, no recordings, a couple of handwritten notes but the information is out of context,” Sims said.

Some scribbled notes from interviews, Sims said, were “illegible.” Other notes he could make out, but they lacked any indication of what questions had been asked by inspectors, making it hard to put information in context.

Sims decided he would have to do his own investigation with the assistance of a Kentucky State Police trooper. But by then, time was working against them.

“Once the incident occurs, there is kind of a ticking clock about getting a proper investigation to get criminal charges,” he said.

A detective interviewed five people present the day of the accident — including witnesses KY OSH never interviewed.

Sims decided to pursue homicide charges relating to Grant’s death.

The detective presented his findings to a grand jury. But the grand jury did not issue any indictments.

“I feel because there was that delay, it impaired our chances of getting a criminal indictment,” Sims said.

Sims was so discouraged by the experience that he wrote a letter to regional officials with the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), detailing what he found in the KY OSH investigation.

Had the original investigation by KY OSH been more helpful, Sims wrote, he could have more thoroughly evaluated the incident to help the family seek justice.

“Unfortunately,” Sims concluded, “I am sure many criminal actions have gone unprosecuted as a result” of poor investigations by KY OSH.

Bluegrass Agricultural has since closed. A “for sale” sign is on the gate near where Grant Oakley was crushed by the forklift tire. The business was owned by a father and son, both named Bobbie Prewitt. The elder Prewitt died in January 2018.

Reached by phone, his son Bobbie Prewitt declined to talk. “That’s something in the past that should stay in the past.”

‘Numerous Deficiencies’

In roughly half the country, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, has direct responsibility for work safety regulation. But in Kentucky, those tasks fall to KY OSH. Federal regulations allow the state to carry out inspections, enforcement, and other work safety programs with the caveat that they be equal to, or better than, what the federal government would provide.

Pam and Mike Oakley looked at the state agency’s investigation at Bluegrass Agricultural and did not think that the KY OSH was living up to that standard. They filed a federal complaint about how the state had conducted the investigation of Grant’s death.

OSHA’s regional director, William Cochran, looked into their concerns and largely agreed.

Cochran, who works in OSHA’s Nashville office, declined an interview request through a spokesperson. But in a December 2016 letter to state officials, Cochran detailed problems with the KY OSH investigation.

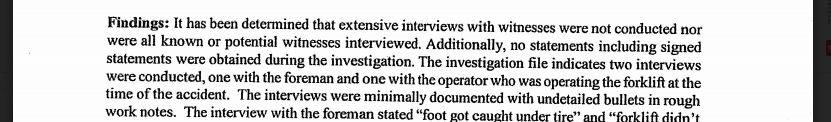

Among them: Kentucky’s case file identified eight potential witnesses, including other employees, a farm manager, and a doctor who was a customer at the business and tended to Grant until an ambulance arrived. But the file contained only minimal documentation for two interviews done on site. The inspector failed to obtain signed statements. Taken as a whole, his letter said, it was impossible to determine if the company should have faced stiffer fines and more serious violations.

The only violation KY OSH assessed against Bluegrass Agricultural was a “serious” violation for allowing an employee to ride as a passenger on the side of the forklift. The Oakleys believed that violation should have been elevated to a “willful” one, which carries higher financial penalties for employers.

But Cochran found that, due to the state’s incomplete investigation, “it is not possible to determine if a willful violation existed.”

KY OSH and officials with the Kentucky Labor Cabinet declined an interview for this story. But in a January, 2017, response to OSHA, the Labor Cabinet pushed back. Ervin Dimeny, then the workplace standards commissioner, wrote that KY OSH did not interview others at the scene because the inspector determined that they were not eyewitnesses to the accident.

Dimeny also objected to OSHA’s recommendation that state inspectors should secure signed statements.

“It is Kentucky’s experience that obtaining signed statements may be counterproductive,” Dimeny wrote.

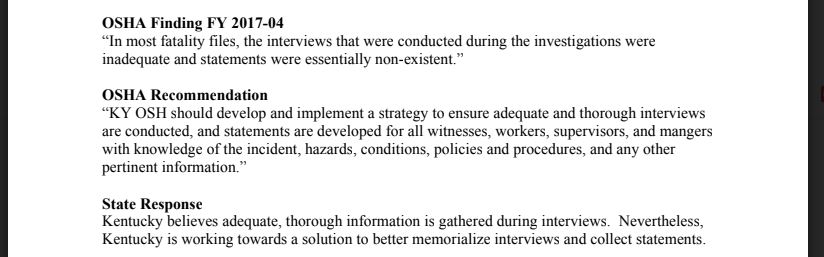

Later, Cochran would find that the flaws the Oakleys had complained about were not an exception to the state’s performance. Rather, they were the rule.

As part of an annual federal oversight report released this year, known as a Federal Audit and Management Evaluation (FAME) report, Cochran conducted a special review of the KY OSH fatality investigations over a two-year period. That report found “numerous deficiencies” in nearly every case. In roughly a quarter of the cases, KY OSH identified workplace hazards but did nothing to correct them. Cochran found no documentation in the KY OSH files to indicating that the state inspector had considered whether there were violations of safety standards.

“The result is workers are continuously exposed to serious hazards that remain unabated,” Cochran wrote.

As with the Grant Oakley investigation, Cochran’s review found KY OSH frequently failed to interview witnesses, secure statements and determine a cause for fatal accidents.

He added that, in some cases, “it appears that the state is just taking management’s word.”

The Oakleys were shocked to learn that the already modest fine KY OSH assessed against Bluegrass Agricultural had been reduced. The initial penalty of $7,000 was cut in half based on a formula the agency uses to lower fines for small businesses.

After their son’s death, the business was ordered to pay $3,500.

“We can tell you what the state of Kentucky OSH thinks what a 17-year-old boy’s life’s worth,” Pam Oakley said. “And it ain’t much,” Mike added.

‘They Put Their Trust’ In KY OSH

Ron Hayes is all too familiar with the Oakleys’ experience. His son Pat died at 19 in a workplace incident in Florida, and the experience turned him into a lifelong advocate for families of those killed on the job.

Hayes said the quality of KY OSH investigations can have enormous emotional and financial implications for the families.

That begins with the effects on the workers’ compensation payments in fatality cases. When KY OSH fails to assign blame or blames a worker, it can lead to a family receiving a lower payout.

Often, he said, the money is far less important than the signal it sends to families.

“They put their trust in them,” he said of KY OSH. “Then when the investigation comes back that did nothing or really found nothing, then you’re left there suffering even more and your trust is betrayed.”

Hayes said a more thorough investigation would at least provide some answers and allow families to better come to terms with the circumstances of their loss.

“You cannot bring back their loved one,” Hayes said. “But what you can do is help them move through the process a lot quicker and help them heal a lot quicker.”

Pam and Mike Oakley were not surprised to learn that federal officials had found so many problems in the KY OSH program.

“Everything about it is a slap in the face and disrespectful to that individual and that family,” Mike Oakley said of the KY OSH work. “And all we wanted was some answers.”

Pain Brings New Mission

Sitting in their living room, beneath hunting trophies Grant and Mike had collected, Mike and Pam shook their heads, smoked, and read over the latest federal report outlining the many flawed investigations.

The more they learn about the many worker fatalities, the deeper they have become involved. The Oakleys have helped to organize an annual workers’ memorial event in April, where the names of those killed on the job are read aloud and families gather with photos, memories, and to share their frustrations with the state agency charged with enforcing worker safety.

“There needs to be somebody with some knowledge, some compassion, to help families like us,” Mike Oakley said.

Mike is becoming more active in worker safety training, too, focusing on young people entering the workforce.

“If I can save one father, one mother, from sitting here, to not have to do this,” Mike said, “Well, that’s one. That’s worth it.”

Artifacts of Grant’s life are all around, and each triggers a short memory or story: The initials he scrawled into wet concrete, the baseball pitching target he’d drawn on a barn door, the garage where he and his dad rebuilt a classic bike.

But there is also that view across the street, which brings back the worst day of their lives and their many unanswered questions.

As the November anniversary of Grant’s death approached, the Oakleys were moving belongings to a new house, farther from the painful site. The house where they raised Grant, which has been in Pam Oakley’s family since the 1950s, is now for sale.

Jeff Young is the managing editor of the Ohio Valley ReSource, a regional journalism collaborative anchored at Louisville Public Media. Contact Jeff Young at (502) 814-6557 or [email protected].

This story is part of a series of reports called Fatal Flaws, originally published by the Ohio Valley ReSource, the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting and the Center for Public Integrity.