Some call it the Rappahannock Hustle, and the many who do it need no further description.

It’s the way to make ends meet by stitching various small jobs, formal and informal, into a livelihood. It helps prop up the local economy. But it also hews tightly to two challenges facing Rappahannock County’s younger population: stable, well-paid work and affordable housing.

Addressing those challenges matters more as the overall population ages and as other rural counties compete to draw in people who bring new ideas and vibrancy.

After years of population loss, rural areas added around 33,000 residents nationwide between 2016 and 2017, the first time since 2010, according to an analysis of census estimates by the USDA’s Economic Research Service.

Quality of life is the No. 1 factor pulling people toward more rural, low-density counties, says Ben Winchester, a researcher at the University of Minnesota Extension who studies what he calls “brain gain.”

“That includes things like recreational opportunities, less traffic, less congestion,” Winchester says.

Those things and more are what draw people to Rappahannock — home to rolling hills, starry night skies and a slower pace of life seldom found so close to a bustling metropolis. All ages and political persuasions here harbor a love of the natural environment.

Gaining access to it means facing certain challenges, and if you are young those hurdles can be higher.

Artist Kat Habib, 33, moved to the county in 2013 and has picked up work doing everything from painting houses to making coffee to bartending to property management.

Twenty-four year-old Tessa Crews has worked as a shop attendant and served at wedding parties. She now works as an innkeeper at the Inn at Mount Vernon Farm, does part-time design work for an Australian publishing company and picks up babysitting shifts.

“It’s incredibly hard to make a living,” says Habib. “And it’s beautiful to be here and it’s good to be here, but the cost of living is very high.”

The Hustle is typically associated with urban communities, the grind of which many who move here are escaping, but local housing’s high cost and limited stock, paired with that paucity of reliable, steady work, make it a necessity.

A shortage of full-time jobs that pay a living wage, with benefits — particularly for college graduates — impacts all age groups in Rappahannock, not just those under 40 like Habib. Piecemeal work and part-time gigs — frequently as part of the underground economy — are more readily available. Folks cobbling these work opportunities together are often younger and single.

The rural economy has become more diversified, said Winchester, who studied rural communities in Minnesota and Nebraska. He found evidence there of people holding a diverse array of jobs and more self-employment. Those characteristics have echoes here in Rappahannock.

“You have to be more creative when you live out here,” says Sperryville Realtor Cheri Woodard, herself a long-time entrepreneur. “You have to think about what you can do, what skills you’re bringing, what can you offer to people.”

Photo: Sara Schonhardt, Rappahannock News

That’s true for Crews, who grew up in Rappahannock and officially moved back late last year. She’d been gone long enough, she says, to realize what was special about the county.

Like others, she discovered that knitting together an income in the Hustle economy relies on word of mouth.

“If you look online it doesn’t exist, but as soon as you start talking to people, that’s how it happens,” Crews says.

Forming that local connection isn’t always easy or immediate, but the advantage often goes to those like Crews who grew up here or have some connection to the county.

A numbers game

Job availability is one thing; willing workers is another. Help Wanted signs hang in windows around the county, but small business owners say they struggle to find employees.

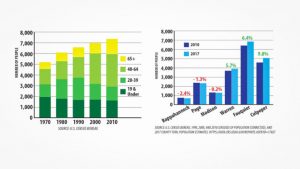

“I cannot find young people that want to do the work that we do,” says Adam Kerr, 39, the founder and president of Rappahannock Landscape & Nursery. That’s not unique to Rappahannock. But part of it here is also a numbers game. “There’s not a lot of young people,” he says.

Kerr pays his employees well and offers them some retirement benefits.

But finding a way to pay Rappahannock rents often over $1,000 a month is tough on a $10-an-hour salary, which is more common.

“There’s work here if you want to work,” says Habib. “The question is, can you rely on it from week to week, and that’s tricky.”

Cara Cutro grew up seeing her parents leave the county to make their livings, so when she decided to come back after six years away, she just knew she’d find a way.

“Part of what’s allowed me to survive here, aside from feeling very strongly that this was my home, was working multiple jobs, having multiple hats,” she says.

Cutro started working in restaurants and then created a mobile massage business. She diversified her services to include private online coaching and medicinal herbs. In 2016, she opened a physical location in Sperryville, Abracadabra Massage & Wellness, but has continued to pick up landscaping work when needed. She also shares her home with a roommate.

“You have to be determined that you’re going to live here, and you have to make it work,” she says.

That determination often comes with some deeper connection, and people who haven’t grown up here may be less inclined to stick it out.

Aron Weisgerber, 33, built the home he now shares with his wife and two children on land his parents own. He realizes that gives him an advantage — though he still pieces together work in construction, solar panel installation, realty and outdoor education.

Photo: Sara Schonhardt, Rappahannock News

Woodard concedes that real estate is expensive overall. There are homes under $250,000 and some rentals under $1,000, which she says are “very desirable.” But Airbnb is taking up some potential rental spots, and some are tucked away on private property, reserved for friends and family.

“Our inventory here is small,” she says.

Community is key

Another shortfall, say some residents under 40, is the lack of a social scene or a place to meet new people.

“There’s nothing here, aside from going to the bar, and there’s not that many of those either,” says Kerr, who picked up side work in order to build his business.

He has a young son and much of what’s kept him in the county is the support of his family. For a young family to come here and do it on their own, he says, “that is just mind-blowing to me.”

Habib looked at other counties in the region and liked them because they were more affordable and had larger populations of people under 40. She chose Rappahannock, she says, because it felt like the Virginia of her childhood.

What’s kept her here are the outdoors and finding a house that she says really feels like home. More importantly, she’s found a creative, supportive community.

“There’s many of us that are creative and seeking our dreams,” she says. “We’re not the nine to fivers. If we were we wouldn’t be here because we couldn’t survive.”

Others agree; it’s the people that make this place.

Researcher Winchester says he’s found that jobs are less of a priority for people looking to move to a place like Rappahannock.

“Ultimately people would look around, and they looked for a community before they looked for a job,” he said.

But that can lead to underemployment, said Winchester, be it a lack of full-time work or work that deviates from one’s skill set.

Not all doom and gloom

It’s not unusual for high school graduates to leave small towns for college or other opportunities, says Winchester, who cautions towns against “feeling bad about losing their young people.”

“What they should be working on is letting their young people know they have some place to come back to,” he adds.

Habib, who is from Warren County, grew up coming to Rappahannock and loving it. She is a studio potter and makes floral arrangements. She also has a steady part-time job managing a career and college access program at Headwaters, a nonprofit group supporting local public education, that provides about half of her income and allows her to spend more time in her artist studio.

While the Hustle makes life hard, for many younger residents it can allow them the flexibility for creative projects and passions.

Photo: Sara Schonhardt, Rappahannock News

Maya Atlas, 28, found her path to Rappahannock through her mother, who bought a home and started harvesting lavender. Atlas, who moved out with her partner last September from D.C. to take over the farm, bartends at Francis for a paycheck and helps milk cows and make butter for a neighbor. She has picked up various jobs both out of necessity and a desire to meet people.

Atlas says she brought some of her city pace with her and has since learned to scale back a bit. But the learning curve has “been exponential,” she admits. Like many who just make the leap, she says she was perhaps naively unconcerned with finances.

“We will make it work,” she says. “It’s just a matter of what level of hustle you have to put in.”

Still, a slower pace can frustrate people wanting to see progress made, including better broadband access.

For Erin Antosh, 34, who runs an online consulting business, connecting with clients took a toll. She found herself driving to Warrenton, where she had a small office, and spending less and less time being able to enjoy the things that brought her to Rappahannock — the scenery and outdoor recreation. She moved up to D.C. recently to be better connected.

“Rappahannock has the potential to be a place for young people to live and thrive,” says Crews, who sees her job at the Mount Vernon inn as a way to advocate for what’s special about the county. “But there are serious hurdles that still need to be overcome.”

This article was originally published by Rappahannock News.