Footpaths, bike trails and car tours guide tourists and locals alike through the region’s natural and cultural heritage. The spending that accompanies the use of such trails has helped revive local economies. But wage levels remain a challenge.

Second in a series, Read part one

EDITOR’S NOTE: Jacob Stump grew up in rural Southwest Virginia while the region developed some of the infrastructure and businesses that today help generate nearly $1 billion in tourism expenditures. Stump teaches international studies at DePaul University in Chicago. In this series of articles, he combines his insider knowledge with his academic training to look at the complex impacts of a tourism economy on a rural region.

In Southwest Virginia, trails are key infrastructural components of the nearly $1 billion annual tourist economy. They link unincorporated communities, small towns and cities, and natural wonders into networks of local economic growth organized around outdoor tourism.

For most of the 20th century, the Southwest Virginia trail infrastructure was considerably less developed. Jobs in the region were mostly clustered in post-World War II industries, coal power, and small farms. There was little impetus to develop a trail infrastructure.

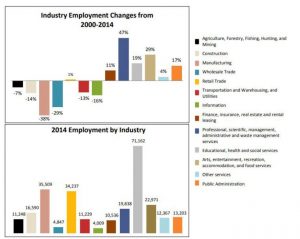

But the 1980s and 1990s saw Southwest Virginia hemorrhage manufacturing, farming, and mining jobs, like other areas in Appalachia and the Rust Belt. A 2016 report by The Friends of Southwest Virginia showed that from 1990 to 2014 the region experienced a 46 percent decrease in manufacturing and 45 percent decrease in mining jobs, for example.

Jobs numbers in Southwest Virginia are still at a net loss today, the report shows. New jobs in recreation, service, and entertainment have helped replace the two decades-plus losses. But the new jobs are often seasonal, part-time, lack benefits and healthcare, and are minimum wage or near-minimum wage (a difficult labor market condition that I plan to explore in installments of this series on the Southwest Virginia economy).

Nonetheless, the regional trail economy has played an integral role in the process of economic recovery. The actual market size is unknown because there are no comprehensive numbers on the annual economic impact of trails for Southwest Virginia.

Consider some of the more prominent examples of the trail economy and its impact on local markets.

The Appalachian Trail was established in 1937 as a 2,190-mile trek. The AT hosted approximately 2,700 “through-hikers” last year from Maine to Georgia and thousands more “section-hikers.”

The town of Damascus organized the annual “Trail Days” festival in 1987. Today, 25,000 people attend and Mayor Jack McCrady reported that the weekend celebration generates approximately $40,000 annually in tax receipts.

The Trek, an organization and website focused on long-distance hiking, administers a survey annually. They found that four in 10 Appalachian Trail thru-hikers and section hikers attended the Damascus Trail Days festival in 2016. This same survey indicates that approximately 75 percent of thru-hikers spent between $4,000-6,000 or more over the duration of their hike. Some of that money was undoubtedly spent at Damascus-based outfitters, restaurants, and shops, as well as numerous other towns and communities along the trail.

Congress recognized the 34-mile long Virginia Creeper Trail as a National Recreation Trail in 1987. Today, 250,000 people ride down the Creeper every year. It has become recognized as the crown jewel example of a successful trail economy, as a couple of people I talked to noted.

Towns like Damascus and Abingdon reap the most benefits from tourism in Southwest Virginia. Damascus Mayor McCrady says that his town generates $450,000-500,000 annually from the Creeper. Small businesses in places like Whitetop, Konnarock, and Taylor’s Valley also benefit. The Creeper Trail Café in Taylor’s Valley exists almost exclusively because the Creeper connects thousands of bicycle riders to the unincorporated mountain community that only has one other business, a country store heated by a woodstove.

Numerous other trails have been developed since the 1990s around the region, and most of them have had a positive impact.

The town of Galax started the New River Trail in 1987, but it was not completed until the 1990s. Like the Creeper, the New River Trail is based on an abandoned rail line. Now the trail is 57 miles long and runs parallel to the New River for 39 miles.

The Friends of Southwest Virginia study shows that over the past decade-plus, Galax enjoyed the largest positive change in tourist expenditures of any locale in the region. Pulaski, which sits at the opposite end of the trail, was second on the list.

A Virginia Tech study estimated that the New River Trail accounted for 2 percent ($238,279) of the 2010 Galax’s total tax revenue. Galax director of tourism and community development, Ray Kohl, said to me by phone that the upward trend continues. In 2017, nearly 1.2 million riders used the trail. And, according to another recent Virginia Tech report, New River Trail visitors spent over $31 million last year.

Norton is another hub in the tourist economy of Southwest Virginia. The town won the 2017 Blue Ridge Outdoors magazine’s “7th annual top adventure town contest.” The Flag Rock Recreation Area was key to this victory.

City Manager Fred Ramey told me that 2008 marked the year of change, a shift away from an energy-centered economy to an outdoors-recreation based economy. As energy companies pulled out of Southwest Virginia and migrated toward the Marcellus Shale discovery in Pennsylvania, Norton started to take advantage of its “fortunate location” and develop the lower slopes of High Knob.

Norton has transformed 25 acres of 1,000 into nine miles of mountain biking and hiking trails. The goal is 30-plus miles of trails. Already, the Flag Rock Recreation Area serves as the staging ground for a series of annual outdoor events, like the High Knob Hellbender 10k, the Cloud Splitter 100 ultra trail marathon, and the Woodbooger Geocaching/Geo Trail event, all of which bring participants from across the U.S.

Towns, communities, and other stakeholders in Virginia’s coal counties that surround Norton, like St. Paul, Haysi, Grundy, Appalachia, Pennington Gap, and Pocahontas, started to develop Spearhead Trails in 2006. The Mountain View Trail opened in 2013, and since then 400 miles of all-terrain vehicle and motorcycle trails have been built across five areas.

Duane Miller is the executive director of the LENOWISCO Planning District and has been a central player in the development of the Spearhead system. Miller told me that “growth has been wonderful.” On weekend days, Miller said, gas stations and car washes in his hometown of Appalachia have enjoyed a substantial uptick in business.

A recent report by the Southwest Regional Recreation Authority shows between 2013 and June 2017 the Spearhead Trail system cumulatively generated upwards of $21.8 million.

Still more trails crisscross the region, like the Crooked Road, the Mountain Brew Trail, and the Backcounty Discovery Route Mid-Atlantic, the last of which just opened this year and originates in Damascus.

Trails and outdoor recreation attract locals and non-locals alike who contribute to the process of Southwest Virginia’s and Appalachia’s post-industrial economic development. They mark an imperfect but positive trend to decades of jobs losses. The real political-economic struggle for communities, municipalities, and business owners is to translate that economic activity into higher quality jobs and wider-spread prosperity.

This article was originally published by Daily Yonder.