Student teams from across the coalfields of eastern Kentucky came together at the Knott County Sportsplex, bringing with them drones that they themselves had built. It was time for the climax of this year-long project. A basketball court had been separated with nets, and padded gates marked a circuit course for the little flying machines.

Seth Hatfield was one of dozens thumbing the joysticks on a remote control, and making last minute adjustments to four colorful propellers on top of a machine that had taken a full school year of teamwork to build. It was time for the drone race.

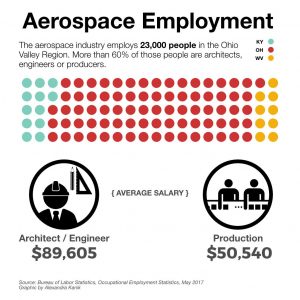

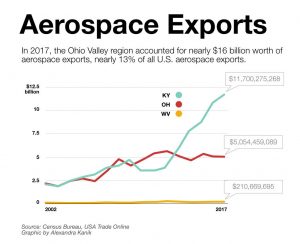

The Ohio Valley has a long history as a leader in aerospace engineering and the economically struggling communities of eastern Kentucky are hoping drones will be a part of the region’s future.

Factories in eastern Kentucky already produce parts for military and civilian aircraft, and local universities offer strong training programs. Nearby Morehead State University is known for tiny satellites that students design.

Paul Green is the Appalachian Technology Initiative for the Kentucky Valley Educational Cooperative, a cooperative of eastern Kentucky school districts. When he went to visit Morehead State with other educators, professors there told him that while they have plenty of students who are academically strong, few arrive at the university prepared to actually do the work of building satellites.

Inspired by a drone racing TV show, Green and his colleagues decided to use their grant funding to purchase drone kits that student teams would have to assemble and then learn how to race around a course.

Students weren’t provided much in the way of instructions.

“It’s project-based learning in its true form,” Green said. “You’ve got to figure this out.”

A Rising Industry

There’s a growing possibility that the skill set of building drones could prepare students not just for college, but also for finding a good job close to home, and helping to grow a new industry.

USA Drone Port is a new initiative that has launched as a collaboration between the Hazard Community and Technical College and a wide variety of local partners. The group kicked into gear after the Trump Administration announced it was looking to fund drone testing grounds, and issued a call for proposals.

USA Drone Port didn’t end up winning that grant but it has been making strides all the same. It received a donation of 50 acres of land at an old strip mine on the Knott-Perry county line, and now has funding to build its first structure on the site. Several local drone businesses have already been launched, and the drone port’s training events have taught drone basics to people across Kentucky. Visitors from across the country have come to learn how drones can be used as an aid in police work and search and rescue efforts, among other areas.

Bart Massey, director of USA Drone Port, said that drone companies working in urban areas often have to travel for hours to reach unrestricted airspace where they can test their machines, and then hours back to their offices to make changes.

Airspace in this corner of rural eastern Kentucky has fewer limitations, so Massey can pitch the drone port as a place where businesses can test, build, and tweak all in one place. He said he’s hearing from companies that are interested in relocating to eastern Kentucky to take advantage of the drone port’s offerings.

Similar initiatives are budding in other corners of central Appalachia. Just across the ridge line in Appalachian Virginia, Mountain Empire Community College has received funding from the Appalachian Regional Commission to “train students, including former coal industry workers, to operate drones and drone sensors,” which they expect can be used for mapping, as wells for surveying and building industrial sites.

A third initiative, led by Maysville Community College, also received funding from the Appalachian Regional Commission to train workers for the drone industry in 20 counties across northeastern Kentucky and southern West Virginia.

The Competition

The drone race in 2018 was the second that the cooperative has held, so some teams were coming in with experience.

CREDIT BENNY BECKER / OHIO VALLEY RESOURCE

Franklin Combs of Knott County Central High School came into the day feeling hopeful. He’d had a strong finish the year before.

“Two people made it around the course last year, and he made it around smoother so he got first place and I got second,” he recalled.

Combs said he’s planning to join the Air Force after graduating high school, and would love to come back to the area if the drone port has grown to a point where he can find work there. “Hopefully, that drone port will bring in bigger industries, and that will build up this economy we have, and keep people here.”

The race itself was gripping and dramatic. There were a lot of crashes, and in many cases, the drones didn’t recover. Combs was relatively lucky on that front— his drone crashed into the netting surrounding the course, so once he had untangled the propeller he was able to keep flying.

CREDIT BENNY BECKER / OHIO VALLEY RESOURCE

Some collisions were more dramatic and damaging. The team from South Floyd Elementary, which was the only all-girls team present, and one of the youngest, hit a major snag when their drone took a big hit during pre-race testing.

“It shot up to the roof, hit the roof, came back down and the battery bounced out of it, and it broke the strap,” Haley Slone, who was piloting the drone, explained.

The team of 7th and 8th graders hurried to fix the drone so they would still be able to compete— scrambling to adjust the tightness on the propellers and re-solder connections for the engine. But they weren’t able to get the drone flying in time.

Still, the South Floyd Elementary team said they took a lot from the experience and were excited to try again next year, and hopefully have more success.

CREDIT BENNY BECKER / OHIO VALLEY RESOURCE

Kansas Stumbo enjoyed the experience so much that she wrote in a school assignment that she wants to have a career building drone parts. She said that soldering was really different from anything else she’d gotten to do in school, and she’d really loved it. “It’s very simple to do, just melting metal to wires,” Stumbo explained.

The Drone Ace

At the end the day, 11th grader Seth Hatfield of Belfry High School emerged as the winner, having flown two of the cleanest and quickest laps through the course. Hatfield had also won in 2017, and said he’s interested in studying aviation at Eastern Kentucky University, and would love to come back and work with drones if the industry can get going, which he’s optimistic about.

CREDIT BENNY BECKER / OHIO VALLEY RESOURCE

“The future of aviation is turning more into drones,” Hatfield said. “People definitely don’t think of this when they think of drones. They think of maybe military or something they heard on the news. It doesn’t always have a positive connotation to it, but it really is the future of this area.”

Hatfield said he’d be excited to be a part of that future.

“I don’t want to move away,” Hatfield said. “I want to stay here and see this area flourish.”

This story was made possible with support from the Solutions Journalism Network.

This article was originally published by Ohio Valley Resource.