What does it mean to be a good citizen? How do you grade yourself on civic participation? Communications strategist Tom Cosgrove says that rural people have a rich story to tell when working through the divided politics of the moment.

Rural advocates don’t necessarily think the nation is more divided than ever before, but they do worry that today’s divisions are more dangerous now than in the past.

That’s one observation of Tom Cosgrove, a communications strategist who has worked in politics, business and nonprofits and is now exploring what Americans think about good citizenship and civic participation.

In advance of last month’s National Rural Assembly in Durham, North Carolina, Cosgrove conducted an informal survey of conference participants and their associates, asking their views on concepts like patriotism, equality, justice and freedom.

He used his findings in a session at the Assembly to prompt a focused discussion on American civics in a time of sharp disagreement. He said rural people have some unique viewpoints of what it means to be a good citizen. It starts with showing up, he said.

“Things only work when enough people show up, and that takes almost everyone playing a role,” said Cosgrove, who grew up in rural Pennsylvania and retains family ties there.

The Daily Yonder interviewed Cosgrove after his Rural Assembly presentation to learn more about what he found in the survey responses.

Bryce Oates: What experience do you have working in rural communities? What made you interested in asking these questions as a survey for Rural Assembly participants?

Tom Cosgrove: I grew up in one of the most rural parts of Pennsylvania, a town with 100 people. I went to a county high school, the county has had a consistent population of around 5,000 people for the last 50 years. It’s gotten a lot older now. My class had about 100 people, but my nephew who’s still around there graduated with 40. So that’s a big shift. I just sort of had that as a background. …

I am interested in the question of democratic values, what are the responsibilities of citizenship? After you’ve thought about that, how do you grade yourself? I’ve asked these questions in four focus groups before, two in Florida, two in Wisconsin. I’m interested in how people think and feel about liberty, freedom, justice and equality. What do people think about the symbols democracy, the flag, about protest and discussion of the Constitution? I’m fascinated as to how people answer this question.

So I said [to the Assembly organizers], “Hey, I’m coming to the National Rural Assembly. Would you be willing to let me have a workshop where I can run a focus group on democracy, values and citizenship?” This was before I knew the theme was civic courage, so everything just kind of clicked.

Oates: What are some of the highlights of the survey?

Cosgrove: The most important question to me is asking people to define, in your own lifetime, (not back in history) what was the moment you were most proud to be an American and when were you the least proud? Typically, now when I ask that, I tell them they have to exclude Obama’s election and Trump’s election. If you don’t, particularly in this group, you’re gonna get the same answer. In the moment, because of the divisive nature of the politics, they’re basically two symbols of the sides. So it’s not as interesting when people are thinking about the state of the country when those choices pop up.

I was talking to my brother, who’s 18 months younger than me, and he said that the most proud he had been was when the Americans beat the Soviets in the 1980 Olympics in hockey. People all had their stories about watching that game. For that whole Cold War period, and in 1980 we can look back and say that was the peak of it. That means you really kind of remember it. Now, that didn’t even come up in this survey. The moon landing came up, which is my personal answer. That tells you when you’re impressionable in life, when you grew up, and what matters to you during that period.

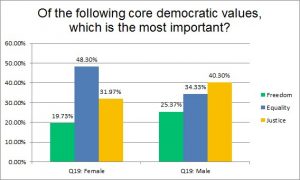

Oates: What about values? What values did survey respondents identify?

Cosgrove: I’m interested in the values question, especially in different settings. I’m finding that the younger America gets the less the melting pot analogy fits with people’s imagery of the country. We are not about masses assimilating into one. We are much more like a mosaic, with our tile pieces that are very colorful and different from each other. But we’re set on the same mat. The question is, what’s in that cement that holds those tiles together? When we talk about equality and justice and freedom, are those values part of the cement? Looking at acceptance of difference, is that part of the mosaic?

Oates: Is there something that makes rural people stand out? Do they answer the survey differently?

Cosgrove: I believe that people who live in rural communities live a different ethic of showing up for each other than many people are able to do, particularly in suburban America. When you extract out people’s volunteerism around schools or their interactions with other people around their kids’ schools, people get even more isolated into their own silos. In rural America, we can’t do that. Things only work when enough people show up, and that takes almost everyone playing a role.

In my hometown, my 26-year-old nephew Billy, he’s the president of the local fire department. The fire department has the carnival and they staff the funeral dinners because they’re in the fire hall. And Billy leads all of the search and rescues. He’s next to a big state park and state forest, and I can’t remember a single person getting lost in their when I was a kid, but these days, there’s a lot of rescues that need to happen in there.

That’s similar to a story I’ve shared about a friend of mine, a politician actually from Maine. He’s been going to the same small town every year in the summer Down East. A couple of years ago he got swept out in a riptide and he had to be rescued. Over the course of the next couple of weeks, everywhere he went he saw people that had participated in the rescue. The rest of that story is that within those small towns, we know who the spectators are and we don’t think much of them. My question is how do we tap that ethos, that “showing up” spirit of community responsibility? Can we use these stories as one more piece of evidence to really bust through people’s really stupid stereotypes of rural America?

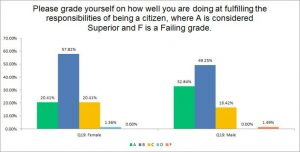

Oates: I was interested to see how you broke the responses down by gender. What was the thinking there?

Cosgrove: To me, the interesting thing for Assembly participants, 70% are women and half have a graduate degree. That brings a certain level of interest and bias in the survey. Still, [men were two-thirds more likely than women to give] themselves an “A” when it comes to civic participation. Most women give themselves a “B.”

What I know from running these focus groups is that when you push the “B’s,” when you ask them why they’re not “A’s,” their answer is “because I could do more.” It’s not that they aren’t patriotic, because that’s a different issue. It’s not that they don’t belong, because they appreciate what the responsibilities are around citizenship. The point is that they know what they’re measuring themselves against. It often comes down to the thought that “I don’t do enough in my own community.” Or, I don’t speak up like I should. I don’t tell my Representative I disagree with them as often as I should, or I don’t go to city council meetings. When it comes to all of those civic responsibilities, I may or may not show up every time I should.

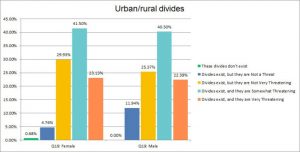

Oates: What about the rural-urban divide question? Does the survey inform that discussion?

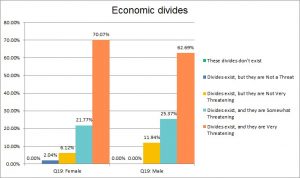

Cosgrove: More people answered that the divides are more dangerous than answered “this is the most divided I’ve seen the country.” We don’t have a way to dig into that directly, but I’d guess this represents an older group of people that can remember back to 1968, the whole 1960s really, so they can remember a time where there was much more division. But still, they have a feeling that the whole system is more at risk today. And then when we ask why, it’s not because they see a geographic split, though there is a little of that. It’s not because there’s a rural-urban split, although there’s a little bit of that. It really comes down to economics and race. Those are the two big reasons. Political divides took a third place, but that was significantly below economic divides and racial divides.

Oates: What about rural people and their history in a place? How does that fit in?

Costgrove: Ruby Sales [who spoke at the Assembly] is creating this center in memory of the black scholar Vincent Harding. When speaking up in a meeting or in a circle, Harding always asked you to tell your momma’s name, to share where she was from. And so the question in the survey, do you know where your maternal grandmother was born, it comes from Dr. Harding. And what was interesting there within this group is that 15% didn’t know, and that sparked a bunch of conversation. On the other hand, it’s interesting that such a big chunk of the people in this group still live in the same county that their grandmother was born in. That would not be the case in Boulder, or in Detroit, or in most urban and suburban areas.

There’s a lot in here about how people define hometown. Even without the grandmother question, is your hometown where you born? Is it where you grew up? Is it where you live today? There was a huge chunk of people in this group who lived where they were born and raised. It was only a small chunk, 20%, that answered that my hometown is where I live today, but they have no history there

When I’m looking around, and thinking about that cement on that mosaic map, I’m considering what people mean by “community” and the place they live. Is “hometown” the language we want to use? Is hometown a way we can reference the place we picked up our values? Is hometown a place we learned a work ethic, where we picked something that we carry with us? It’s the thing we don’t want to give up, and that we want other people to appreciate. Is my hometown where I learned about equality? Is my hometown where I learned about freedom? Or am I living in my hometown in a way that embodies the values I took from growing up here? Now, that’s a bigger research project than this. But those questions are there. I think that people will learn a lot if they take the time to really think about these questions, then answer honestly for themselves.

This article was originally published by Daily Yonder.