Heather Adams sat in a line of cars along Kentucky Route 95, cars filled with parents who had just received the call no parent wants to get: A shooting at her child’s school, Marshall County High in Benton, Kentucky. Two 15-year-old students were killed and another 18 injured.

Adams was waiting anxiously to pick up her children, a 15-year-old and a ten-year-old. Both were safe and so she could relax enough to talk a bit. Earlier, she was at the high school with other frantic parents looking for answers about their children.

Nicole Erwin | Ohio Valley ReSource

“I noticed a lady that was distraught, couldn’t find her child,” Adams said. Adams was texting with her son, and tried to get information for the other parent. That’s when they both learned something terrible.

“That was the shooter’s mother,” Adams said. She said the woman went into what seemed like shock.

“I held her hair while she threw up.”

Adams says the mother was in shock.

“The shooter took the gun out of her closet,” Adams said.

Kentucky State Police have not confirmed how the shooter obtained the handgun used at the school. But if Adams’ account proves accurate, it fits a strong pattern.

A 2004 report by the U.S. Secret Service and the Department of Education found that over two-thirds of students who used guns in violent acts at school got those guns from their own home or that of a relative.

That’s why many states have some sort of child access prevention law to encourage the safe storage of firearms and make adults liable if children get access to guns. Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia do not. Under Kentucky law there is no requirement for secure storage of weapons, and adults are liable only if they “recklessly provide a handgun” to a minor they think might use it illegally.

Safe Storage

“We know that those laws work,” Hannah Shearer said. She’s a staff attorney at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, which formed after Arizona U.S. Representative Gabby Giffords was shot in 2011.

“There is research that states that have child access prevention laws have successfully reduced unintentional gun injuries among children and also child suicides,” Shearer said. “We know that in states with those laws fewer kids are getting their hands on their parents’ guns and harming themselves with guns.”

Nicole Erwin | Ohio Valley ReSource

Many of the laws have been in effect long enough to give researchers time to assess their effectiveness. A 2000 study, for example, found that Florida’s law, which carries some of the stiffest penalties for not securing a firearm in the presence of children, to be especially effective, cutting accidental child deaths from guns in half.

A 2005 study found such laws in 18 states helped decrease gun injuries among minors by about a third, and a 2013 study supported the findings that child access laws help reduce gun injuries among children. Another study from 2004 showed the laws also helped decrease teen suicides by more than 10 percent, likely saving more than 300 lives over about a decade.

Other studies showed mixed results but the scientific literature is clear on one thing: American children face a substantial risk of injury or death from firearms. Researchers in the field say more thorough study has been hampered by political pressure by gun rights groups to block funding for research by federal agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control.

Failed Efforts

Kentucky State Senator Gerald Neal, a Democrat from Louisville, introduced a child access law in the last legislative session.

“Young people are losing their lives to carelessly stored firearms,” Neal said. “What I wanted to do was lift up the discussion. It is intolerable for us not to be proactive about doing something.”

Neal said his bill is not about gun control but about gun safety. He compared it to laws on wearing seat belts. Still, the bill went nowhere. In Ohio, similar bills met a similar fate in the last three sessions.

“I thought it was just good common sense legislation,” Ohio State Representative Bill Patmon, a Democrat from Cleveland, said. “It seems that the thing that was lacking was how to store and keep your firearm so as not to endanger children and innocent bystanders.”

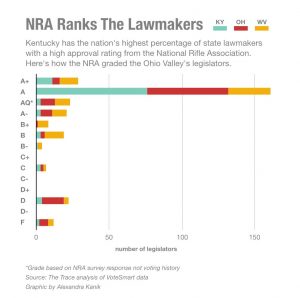

The Ohio Valley region has a high percentage of state lawmakers who get a positive rating from the National Rifle Association for votes or campaign pledges that limit regulation of firearms. The NRA did not return requests for an interview for this story.

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

An analysis of the NRA’s recent lawmaker conducted by The Trace, a journalism nonprofit covering gun violence, shows Kentucky has the nation’s highest percentage, 88 percent, of legislators who got at least an A-minus grade from the NRA. In Ohio, 67 percent of lawmakers got As; In West Virginia, about 60 percent.

Gun culture is strong in this part of the country. But even among some gun owners and Second Amendment advocates, secure storage of firearms is a topic that resonates.

Common Ground

Connie Courtney, of Crestwood, Kentucky, is a volunteer with the Kentucky chapter of the group Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, which advocates for secure storage of guns and background checks on gun purchases. She says she finds a lot of common ground with gun owners around the state, including some who are members of her group.

“Our group does support the Second Amendment,” Courtney said. “I think most people support the same issues we support. It just seems to break down with our leaders in Frankfort and D.C.”

Missy Jenkins-Smith, of Murray, Kentucky, is another member of Moms Demand Action. She is also a survivor of a school shooting, which killed three students and left her paralyzed from the chest down.

Just a month before the Marshall County High shooting Jenkins and others marked the 20th anniversary of a shooting at Heath High School in Paducah, just about 30 miles from Marshall County High. Jenkins said the news of the Marshall County shooting hit her hard.

“All of the sudden it was like my entire body kind of felt weak, like I had the flu or something,” she said.

Today, Jenkins also works as a counselor. What she’d like to see now is community support for the victims.

“They can send letters and cards to people who have gone through this because those are things that I have kept and still have today,” she said. “That is definitely what kind of kept me going. It was kind of like, I went through something and people weren’t forgetting me.

Nicole Erwin | Ohio Valley ReSource

There is another parallel to the Marshall County High shooting. The student who shot Jenkins and others 20 years ago had easy access to the guns in a neighbor’s garage.

Heather Adams, sitting in the car waiting to pick up her children at the Marshall County schools, said she supports the rights of gun owners. She also thinks those gun owners need to secure the guns.

“You have to keep your guns locked,” she said. “Children are impulsive. Their brains are not fully developed and they will act accordingly, and this is what happens when you don’t do the right things with your weapons.”

WFPL reporter Ryland Barton and ReSource reporter Aaron Payne contributed to this story.

CLARIFICATION: This story was modified on Jan. 25, 2018, to add information about Kentucky law and to remove a reference to the number of states with laws regarding safe gun storage.

This article was originally published on Ohio Valley ReSource.