It’s going to affect our businesses for a very long time — probably forever.

Georgia Haverty: It kind of snuck up on me. Slowly. First I heard ‘pipeline’ and went, ‘Oh’. Then I heard, ‘42-inch-wide pipeline.’ Then I heard that MVP has never built one this big… It’s like hearing something from a long distance away. It’s bad. It gets worse and worse and worse.

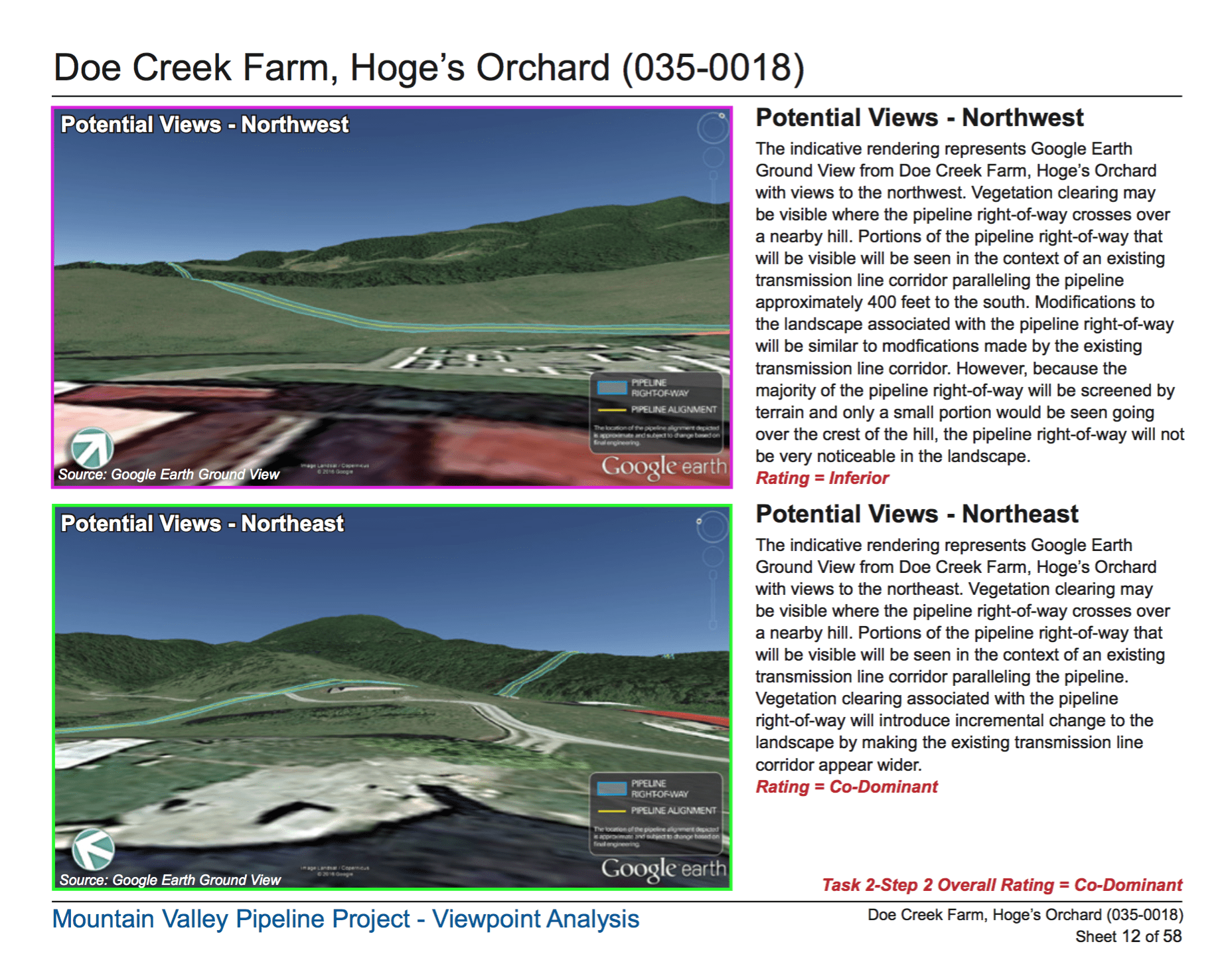

We’re at Doe Creek Farm in Pembroke, Virginia. The farm has been in my family since 1978 and prior to that it was in the Hoge family. The house was built in 1883. There have been apples on this farm for over 100 years. We have cattle and hay. The farm has been renovated in the last five years to provide businesses for my family — my daughter, my son-in-law and myself. We now have pick-your-own apples. We have a wedding venue. We have a dog kennel, a boarding kennel. So hopefully it is going to provide income and has been providing income for both of our families. Our business also supports local businesses. We support local florists and caterers.

It feels pretty awful. The pipeline itself is a private company and they can take our land as a private company just for profit. There are no benefits to the county for this pipeline going through. The property values will plummet. My businesses will suffer. My water could be affected. I have spring water, as do a lot of people along this pipeline. There are many springs in this particular area.

If our businesses, our livelihood, our water are affected, then if we needed to move we won’t be able to because land values will go down. In fact, land values have already gone down in some areas because of the threat of the pipeline, which means less tax revenue for the county.

The entire county is going to suffer from this pipeline going through and there is absolutely no upside to it. None. There are no jobs that will be created.*1 There might be a few construction jobs when it’s going on, but mostly they’re going to bring in their own people to do that. There is no oil or gas that will be given to this county. There is nothing really that we’re going to gain from this pipeline.

There is a request for a 500-foot-wide corridor through the National Forest. We don’t know why. Maybe it’s to keep all pipelines out of the rest of the National Forest, just have them put in one location and having it put in the most economically disadvantaged area would maybe be the best for the Forestry Department. But, that’s fine in the forests if you have a 500-foot corridor in two places. What’s going to happen to the private property on either sides of those?*2

What’s going to happen is they’re going to get the 500-foot-wide corridor in our properties too. So the Appalachian Trail loses. National Forest loses. Landowners lose and a whole lot more people are affected if that goes through. Future pipelines wouldn’t have to fight the National Forest because they’ve already got approval for a 500-foot corridor.

It makes me very sad to see that. It makes me very angry too. But, that doesn’t help.

The path of the pipeline pretty much bisects the property. *4 From where we have weddings — it will be this big, huge scar running right through the property. Because they’ve decided to put this line so close to all my businesses I’m now in what’s called a ‘high consequence area,’ which is a euphemism for blowing lots of people up. *3

If you are ‘high consequence area’ apparently you can get a different grade of pipe. That’s another thing —in rural areas the pipes are not as thick or as high grade as those in heavily populated areas — so our lives are worth a little bit less than somebody in say, Boston. So that upsets us too. I’d like to see a better grade of pipe put under here so I have less chance of blowing people up.

If I look out and I see everything is nice and green again, everything’s fine. But, I know there’s a 42-inch pipeline with high-pressure gas going through it. And it’s dangerous, especially dangerous if the engineers in the pipeline company don’t put it in right. So it’s going to be underground. I know it’s out there and I’m going to feel on edge, constantly, because of this gas running right next to me.

Even after the scar is gone on the pasture — if it is — the people who come here for weddings and to pick apples are going to know they’re sitting right next to a 42-inch pipeline. So it’s going to affect our businesses for a very long time — probably forever.

Georgia Haverty’s parents moved their family farm from Loudon County to Giles County, Virginia to get away from development. Now her Doe Creek Farm is in the path of the proposed Mountain Valley Pipeline.

The proposed path of the 42-inch diameter, natural gas pipeline is one of multiple large-diameter natural gas pipeline proposals under review by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) for construction approval. The MVP’s proposed path stretches 303-miles from Bradshaw, West Virginia to Pittsylvania County, Virginia connecting Marcellus and Utica shale gas production to the Transcontinental Gas Pipeline System (Transco). Transco is a 10,200-mile pipeline network that stretches from New England to the Gulf Coast serving major metro areas and international markets.

FERC is expected to release its Final Environmental Impact Study in June 2017 and a decision to approve or deny is expected in the fall. If approved the MVP will then be able to use eminent domain laws to take land from owners unwilling to sell easement rights. Some Mountain Valley contracts call for the right to install two 42-inch pipelines.

Mountain Valley Pipeline, LLC is a joint venture of EQT Midstream Partners, LP; NextEra US Gas Assets, LLC; Con Edison Transmission, Inc. ; WGL Midstream; and RGC Midstream, LLC. According to the company’s website, a “significant interest’ is owned by EQT Midstream Partners and it will operate the pipeline.

*Mountain Valley Pipeline projects that 34 jobs in Virginia will be created once the pipeline is in operation. MVP spokesperson Natalie Cox was not able to say where the jobs would be located or give job descriptions, “We don’t have that information now, the project not yet even approved.” She added these would likely be hourly jobs to maintain the pipeline, “keep it clean, keep it running, check and monitor it.” Lewis Freeman, chair and executive director of the Allegheny Blue Ridge Alliance, said more needs to be done to study job loss as a result of large-sized pipeline construction. “There could be more jobs lost and perhaps a net economic loss to the state of Virginia, and West Virginia too, not withstanding in the case of West Virginia where there’s upstream revenue from the drilling.”

** According to the National Forest Service’s Frequently Asked Questions: “MVP proposes a 125-ft wide temporary construction right-of-way and a 50-ft wide permanent right-of-way for operation and maintenance. The Jefferson Forest Plan states that new utility corridors with a right-of-way width of 50 feet or greater will be reallocated to the management prescription for Designated Utility Corridors. The purpose of Designated Utility Corridors is to encourage collocation of special uses, like transmission lines or pipelines, to minimize the negative environmental, social and visual impacts that can be associated with long, linear corridors.”

*** Federal regulations in CFR 49 192 describe calculations for determining a “high consequence area” based on estimates of people and buildings near the pipeline. Areas of higher population density have increased safety requirements that include pipe thickness and pressure safety measures, depth of ground cover, distance to shutoff valves and frequency of inspection.

This is part of a series of people and places along the proposed pipelines in Appalachia.

In ‘100 Days, 100 Voices’ Nancy Andrews presents photographs depicting the diversity of voices across Appalachia. These portraits strive to show the varied faces, passions, issues and opinions from around the region. These interviews have been edited for brevity and clarity. If you have an idea for ‘100 Days, 100 Voices’ please contact Nancy Andrews on Twitter @NancyAndrews or email at nancy.andrews [at] mail.wvu.edu. Follow her on Instagram @NancyAndrews.