Hours after President Trump announced his sweeping immigration ban, conservative social media began to circulate press photos of Kentuckians taken during Johnson’s War on Poverty campaign as a form of support. If the connection wasn’t immediately clear, the photographs’ superimposed text drove home the point: why should we care about refugees, the images asked, when poor white Appalachians are suffering on our doorstep?

Although uncreative and callous, the use of these images pulls from the grimier subtext of both historic and contemporary writing about Appalachia, and particularly the political debates about our region that took place during the election. According to some analysis, to be Appalachian is to be poor and dismissed through national indifference, but most of all, it is to be white and therefore more deserving of good will.

Most of us who are from or live within Appalachia know those perceptions to be regional stereotypes. Appalachia is not now nor has it ever been racially homogenous, yet the default Appalachia that exists in the imaginations of many is exclusively white and universally poor. During the election, journalists gave these stereotypes new life by casting Appalachia as the heart of “Trump Country.” Profile after profile offered up Appalachia as home to a unique kind of white voter motivated by sheer economic desperation with little attention paid to our region’s diversity, history, or the roots of its decline. I came to see what I initially dismissed as regional ignorance as a deliberate strategy that allowed writers to discuss Trump’s popularity without confronting the racism and xenophobia within his campaign and among his base.

This strategy trades on the flawed assumption that racism, as such, can’t exist to any significant degree in Appalachia because its regional identity is white and degraded. This suggestion might sound odd, at first, given that writers often use precisely the same logic to argue that Appalachia is a hyper-racist region. What these two positions share, however, is a willingness to use Appalachia as proof of a variety of extremes depending on the needs of the current political moment. The fiction of the deviant hillbilly — think Deliverance — served the 1970s well, for example, because definitions of social progress in part hinged on the acceptance of personal freedoms like women’s and LGBT rights, along with support for racial equality. Locating the antidote to progress deep within mountains and hollers made those outside the region feel more progressive. Our current political climate needed a category of white individuals that allowed writers to make tidier arguments about class while ignoring or deflecting attention to race, and it wasn’t the first time that Appalachians have served that role.

Anthropologist Allen Batteau called it the myth of “Holy Appalachia” — a fiction designed to help repair a society contaminated by the evils of slavery. During and after the Civil War, it became therapeutic, in a sense, to allow a category of white persons immunity from racial hysteria. In other words, Appalachians became the first beneficiaries of the #notallwhitepeople impulse. Citing the existence of Appalachian anti-slavery societies and geographic and cultural distance from plantation slavery, a wide variety of intellectuals — from Abraham Lincoln to Carter G. Woodson — made the case for our racial innocence. If the institution of slavery fundamentally altered the moral compass of whites, it followed that those who lacked exposure to could be spared.

Throughout the nineteenth century, white Appalachians also participated in this myth-making. When outsiders employed the stereotype of an uncivilized Appalachia to justify their economic and social experiments in the region, we often countered with valorized versions of our better selves. The myth of a “Holy Appalachia” is a wholesome fiction, unlike those that resulted in our economic exploitation. And over time, all of our stereotypes — both benevolent and derogatory — came to be embedded in the way that individuals within and outside the region looked at Appalachia through the prism of class.

In Appalachia, class often supersedes race as the defining maker of social status. Our region is shaped by decades of conflict between the working class and those who controlled our industries. Appalachia has yielded sophisticated readings of class and labor history, but these too are complicated by the burden we often carry to tell our stories in ways that refute stereotypes. Labor history, and the history of the region’s class conflict, is the arena where Appalachian writers and scholars have pushed back most forcefully against the myth that people of color were not or are not significant to our region. In drawing inspiration from these stories, however, we often emphasize that black and white workers united in mutual class oppression.

To use a recognizable example, imagine the stirring scene from the film Matewan where a white union organizer makes an impassioned defense of African American miners before an interracial crowd. “There ain’t but two sides to this world,” the organizers says, “them that work and them that don’t.” The hostility that white workers initially felt toward African American miners dissipates because the white workers realize that outsiders want them to fall prey to racism as a way to undermine the union. Although people of color are restored to the region’s history, their experiences remain largely interpreted through their class status and often in terms of solidarity with white workers, which becomes the basis for racial unity. As for racism, the myth of “Holy Appalachia” makes an appearance through the suggestion that individuals outside the region stirred up racial hostility as a means of driving a wedge in communities for their economic gain.

The entanglements of race and class within Appalachia and the function of regional stereotypes within these positions are vast topics. This project is an important example of individuals trying to make these topics more intersectional, but we must also understand the cost of using our region’s history as a political weapon. During the election, journalists, pundits, and the public-at-large often used stories of down-and-out Appalachian whites to deflect growing alarm about the most brutal outcomes promised by a Trump victory. The poor, white Appalachian voter, the script went, thinks little about mass deportations, religious discrimination, border walls, or sinister figures elevated to senior political office. His only thoughts are of his economic survival, and although his position might be naïve, he comes by it honestly through an upbringing deprived of meaningful contact with people of color.

This outlook was strengthened by the publication of two recent books that invited readers into a world populated by white individuals who complicate the universal concept of “white privilege,” or so journalists thought. Historian Nancy Isenberg’s White Trash offers a long look at the changing fates of economically-inferior whites. An academic offering, it pulls race and class apart in order to provide fuller analysis of a dispossessed and often exploited white underclass. Fortunately or unfortunately for Isenberg, her monograph hit the shelves at the precise moment that the country was primed to consume any sort of analysis that might explain Donald Trump’s popularity and particularity his popularity among working-class whites. Another beneficiary of uncanny timing was J.D. Vance, whose self-defined memoir Hillbilly Elegy became the favored text for understanding the inner lives of disadvantaged white voters. Unlike Isenberg, Vance eagerly embraced the role of spokesperson for this group and in the process has left a significant imprint on the way that journalists have covered our region during the election.

What concerns me most about this coverage is its tendency — consciously or unconsciously — to write about white Appalachians as an ethnic minority. Returning to Vance, a central idea in his memoir is that white Appalachians are culturally and ethnically distinct from other white Americans and therefore have a unique “stock” that informs their social position. This is the Scots-Irish myth, repackaged as a political tool. Many individuals within the region or who work in the field of Appalachian Studies have shot back at this not only because it’s inaccurate, but also because he links this distinction to certain pathologies: laziness, violence, poverty, and addiction come immediately to mind. But stepping back from this — and setting down the burden of refuting regional stereotypes — I am alarmed to read such frequent descriptions of white Appalachians that define our relationship to our region and our collective fates as a matter of bloodline. This not only excludes people of color from our shared regional heritage, it comes dangerously close to echoing white nationalism.

Thanks to an election cycle marked by commentary that claims Appalachia is home to a unique group of white second-class citizens with a distinct ethnic heritage, white nationalist are now very interested in our region. The Traditionalist Worker Party, for example, has an extensive yet unsophisticated vision for Appalachia that includes transforming the region into the kind of “people’s community” planned by architects of the Third Reich. At the time of writing, the Traditionalist Worker Party is planning to rally in Pikeville, Kentucky this spring in “defense of white families.” The League of the South, an older hate-group for individuals with “Anglo-Celtic” heritage, is also expanding.

Those of us who are from or love the region have always spoken out against this kind of intellectual dishonesty, but the urgency to do so seems more acute since January 20. I hope that in the process we continue to liberate our history from myths and fictions. Even if the rest of the world seems incapable of looking at the region with clear eyes, we can resist being defined by their gaze.

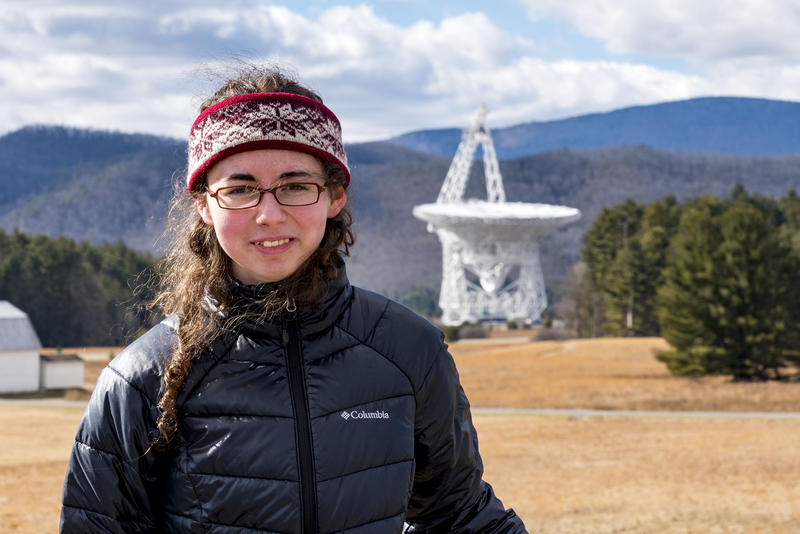

Elizabeth Catte (@elizabethcatte) is a historian and writer from East Tennessee. She is the author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, forthcoming from Belt in 2017. More of her writing can be found at elizabethcatte.com.