The Ocracoke Health Center is one of those vital institutions that keeps the island going, but that doesn’t always translate into fiscal health.

Despite being a business leader in a busy tourist town, Cheryl Ballance sometimes has had to tell summer guests not to come to Ocracoke.

“Sometimes, we’d get calls from people who said they were nine months pregnant with a high-risk pregnancy, wanting to know if we had resources for them,” Ballance said. “I’d tell them, ‘Oh, you really need to look at the map.’”

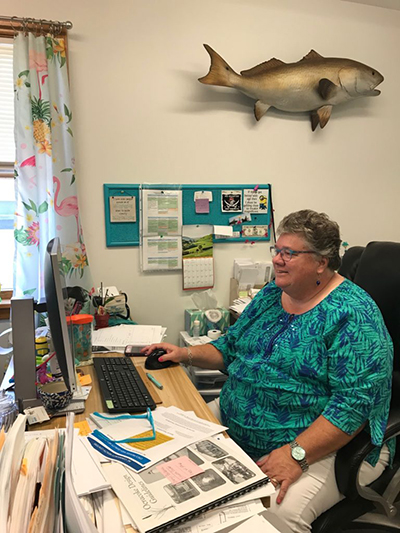

Ballance, the longtime head of the Ocracoke Health Center, has seen and heard it all from tourists and from the thousand-or-so year-round residents on the 13-mile long island, which lies south of Hatteras Island on the Outer Banks. The health center is an important place on the island’s map, as it’s the only place to get consistent health services. The center does not turn anyone away, insured or not.

Supplementing the remote island’s health care is Gail Covington, a mobile nurse practitioner, who provides services in homes on Ocracoke and Hatteras islands, and who does not take insurance.

“On a summer holiday weekend, we have this blossom of you know, maybe 10,000 people who show up,” Ballance said. ”I think it’s probably like seven to 8,000 during the week.”

Despite the center’s importance to the life of Ocracoke, the past few years have been challenging financially. Ballance said she’s making a go of it, but it’s difficult to keep providing high-quality care on a shrinking health care dollar in one of the most remote and sparsely populated parts of the state.

Seasonal Work, Yearround Expenses

One issue for Ballance is about a third of her patients are uninsured, even as they work two, three, even four gigs at a time during tourist season, when there’s work to be had.

“The people who support this whole resort are people who are only employed, if they’re lucky, somewhat in April, May, June, July, August, and if we don’t have hurricanes September and October,” she said. “Then by November, everything is closed.”

“They’re making a year’s worth of income during that five to six month period.”

Some workers do leave the island in winter, Ballance said. Maybe “they have a friend that lives out in the mountains, ‘Can you come up here for three weeks, we’re really busy, you can help us at ski lodge?’”

But for many people on the island, funds begin to dwindle in the lean months of the late winter, especially as unemployment checks peter out. It’s something familiar to Erin O’Neal, the clinic’s chief operating officer, who used to work in restaurants when she’d come home from school.

“Anybody who’s waiting tables, and you got a lot of that, or cleaning rooms, aren’t a high hourly rate, their unemployment is gonna be the lowest,” O’Neal said, noting how the law changed to shorten the number of weeks someone can draw an unemployment check. “And if there was a storm, and they drew on their unemployment during that time, they’ve already used part of their weeks before they’ve even gone out with their season. So it’s an even longer extended period of time with no income, it’s really hard for people.”

The flip side is that winters give the clinic’s doctor, Erin Baker, time to dig into problems.

“In the summertime, she’s clipping those visits for the residents,“ because the clinic is hopping, Ballance said. “But she spends a lot of time, time you’re never going to get anywhere else … in the winter.”

Getting Away Has a Cost

The isolation that tourists crave also poses challenges for the locals.

When Vince O’Neal was a kid on Ocracoke, his only medical encounters were with the school nurse or his grandmother, a midwife who delivered the island’s babies for decades. That was before the clinic started in 1981.

“We did not have any kind of medical services here until that clinic was built,” said the 59-year-old restaurant owner, and, by his reckoning, eighth-generation Ocracoker.

Otherwise, it was off the island to the doctor, a trip that could take hours, or even a whole day.

Access to emergency care from Ocracoke has gotten better over the years. There are always emergency medical technicians on the island and helicopter service to Vidant Medical Center in Greenville or to the Outer Banks Hospital in Nags Head, but there’s no pharmacy and no lab.

Getting off the island takes hours by ferry to the mainland and then to the nearest hospital or an hourlong ferry ride to Hatteras from the northern end of the island and another 90 minutes from there to Nags Head.

So much depends on the ferry. If the weather turns stormy or foggy, the ferries don’t run. Even when they do, getting to a specialist off the island or to the dentist can mean getting up at 3:30 a.m. to get the 5 a.m. Hatteras ferry run. Prescriptions? They come by courier from Hatteras every afternoon.

But if a tourist gets a stingray barb in their foot or a severe sunburn, the center is where they turn.

“We have people who have been coming here for years,” O’Neal said. “They come every season … they’re already in our system.”

Quality on a Thin Budget

Many of the clinic’s child patients are covered by Medicaid, but Ballance said there’s uncertainty about that payment stream too, as the program gets set to transform from a fee-for-service to managed care payment regimen, where clinics such as OHC get paid a set monthly fee in return for providing all of a patient’s needs.

“We want to sign with every (managed care) provider,” Ballance said. “But I don’t want to sign and then I get, you know, 20 percent less reimbursement. I want to get the same reimbursement, like I get with Blue Cross Blue Shield right now.”

OHC has achieved the benchmarks required to be a “quality provider” for BCBSNC, which comes with enhanced payment. But achieving the benchmark to become a quality provider has meant extra work.

“We’re almost at that breaking point. I mean, we’re really on the brink, that we have to hire another person,” she said, noting that the cost of living on Ocracoke can make it challenging to recruit year-round workers. “We don’t earn resort income, but we pay resort prices to live here.”

Even the well-paying patients haven’t been as profitable. Traditionally, the clinic has been happy to treat tourists, who do often have jobs – with insurance – that pay enough for them to come to the island for a vacation. But commercial reimbursements haven’t been keeping pace.

“We barely do a margin in our busy season, June, July and August,” Ballance said.

If it weren’t for the funds the center gets for being a “federally qualified” health center, the fundraising and foundation grants, there’d be no way to keep health care going on the island.

“Health care is vitally important for the island, both to meet the needs of the local community and the tourist population,” said Helena Stevens, who heads the Ocracoke Civic and Business Association. She said her organization supports all of Ballance’s fundraising efforts, such as a seafood dinner later this summer.

She wouldn’t even speculate what losing the clinic would mean to the island.

This article was originally published by the Daily Yonder. It was co-published by North Carolina Health News with the Ocracoke Observer, which has a version in their August print edition. It is reprinted here with permission.