For years, Roberta Lee Levine has baked noodle kugel – a traditional Jewish egg noodle casserole made with apples, cinnamon, cream cheese, cottage cheese, and raisins. “I’ve made it for bar mitzvahs, bat mitzvahs, weddings, ” she said.

“Everybody says I make the best.”

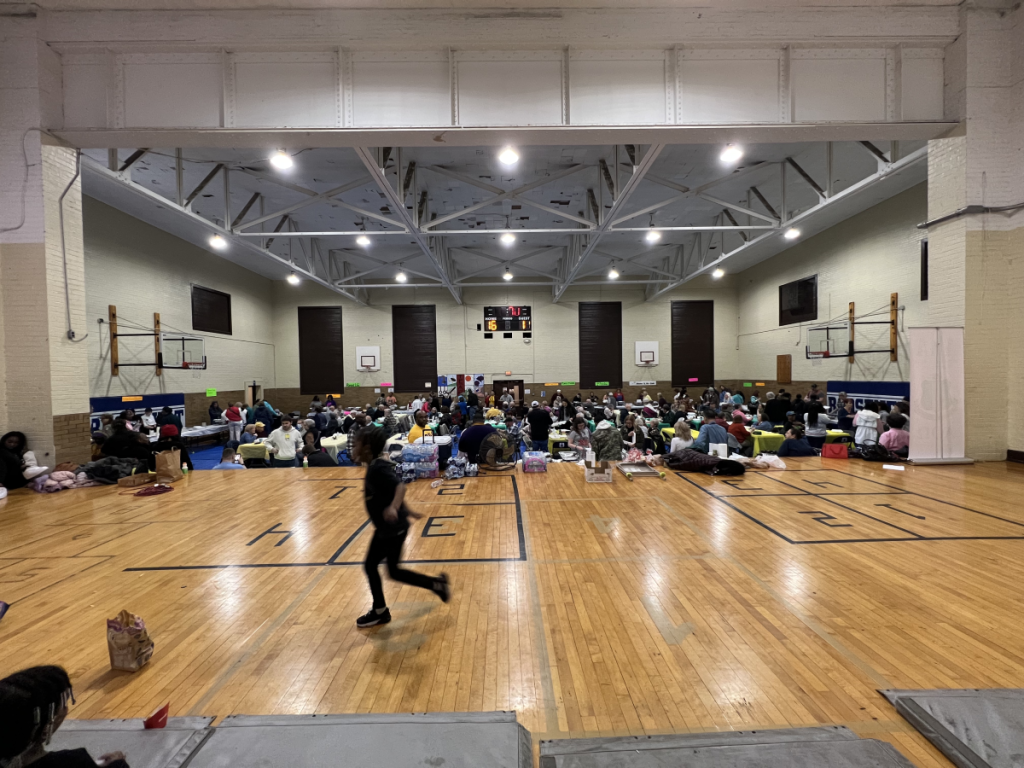

Saturday, Levine and her husband, Richard, serve up her homemade kugel during what local residents call the “dip dinner,” at the East End Resource Center, based in a former junior high-school in Charleston, West Virginia.

The Levines and their kugel are set up on the long side of the gym, next to congregants from First Presbyterian Church serving up the “Presbyterian chicken” – the day’s must-have dish. There are at least three versions of macaroni and cheese. The consensus is that St. Paul’s AME church is the best, though all were creamy and decadent.

Several long tables, crammed with everything from coconut cake and pecan pie to homemade cookies and brownies, to cobbler and cupcakes line another wall of the gym. The desserts were baked by members of Saint Mark’s United Methodist Church and the Charleston Baptist Temple, two churches located less than a mile away from the center hosting the event.

There is a lot of food here.

This community meal is officially known as the Heart and Soul Dip Dinner. The “dip” describes a single serving of food; “heart and soul” reference Valentine’s Day and Black History Month, which like the dinner, occur in February. The event began in 2010 as a fundraiser for the East End Resource Center (EERC)’s senior programs, like weekly lunches and Yoga, but has been on hiatus since 2020 due to COVID-19.

Although the food is important, it’s not the only reason community members from nearly a dozen congregations and other organizations have gathered.

An Appalachian Tradition: Church and Community Potlucks

Religious or not, growing up in Appalachia means you have probably gone to church to eat. Churches in the region often host meals for the broader community. Friday fish fries during Lent and Shrove Tuesday pancake dinners are just two examples.

And like the dip dinner, church meals often serve as community fundraisers. Proceeds from a ramp or spaghetti dinner served at a church might also be a fundraiser to help pay for band uniforms for local high school students or to aid a family who’s lost everything in a fire.

But these gatherings are steeped in cultural history too. Author Mark Sohn describes a variation of the potluck supper in his book, “Appalachian Home Cooking: History, Culture, and Recipes,” called dinner on the grounds. Such meals often marked particular occasions in rural churches across Appalachia, including once-a-month communion services or fall homecoming celebrations.

“Dinner on the grounds gets its name from the fact that food is eaten on church property on temporary retaining walls, church steps, quilts laid on the ground, or any space one can lean against,” he writes.

Food for these church dinners was generally prepared by church women, sometimes in a church kitchen, with particular casseroles and side dishes cooked at home and brought to the church potluck style.

According to Sohn, the idea of dinner on the grounds today has spread to “several denominations, even schools.”

The dip dinner, then, is a contemporary (and indoor) version of dinner on the grounds. And it expands the definition through its inclusion of interfaith partnerships and non-religious organizations, such as students from the Carver Career Center in Charleston who prepared a brothy seafood stew.

Two historically Black Greek organizations – the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority and fraternity Omega Psi Phi – served pork chops, chicken and green beans.

Bobby Robinson, who is a pastor and Omega Psi Phi member, said that “food is an easy way to come together and have fun.” But he also ties it to his African-American and Appalachian experience.

“When African people were kidnapped and brought into this country against their will they were given scraps to eat, but they turned those scraps into delicacies,” he said.

Appalachia, he said, is a distressed area, and gathering around food is important as “a time for uplift and encouragement.”

All are welcome – religious or not

Across the gym from Levines, who just peeled the foil back on their second large baking dish of noodle kugel, Jennifer McIntosh scrapes the last chunks of jerk-style pork from her crock pot. She just moved to the neighborhood last summer from Morgantown, West Virginia, and is originally from Jamaica.

It’s her first dip dinner.

“I wanted to get some kind of participation in the community, and this seemed like a golden opportunity,” she said. “When we share food, we share the joy we have of who we are as a people, and that joy is translatable.”

McIntosh is not religious. But she believes that religion is valuable because it “brings people together,” offering an alternative to the polarization that is gripping the country through community activities like this one.

“I don’t like the divisions we see in our country. I can’t deal with it,” she said.

Events like the dip dinner, Bobby Robinson says, allow people to come together across the political and social spectrum to help each other. “When you talk to people face-to-face, you see the humanity in the other person,” he said. “And we want to foster that process of seeing the goodness in people.”

Laura Harbert Allen is a Report for America corps member covering religion for 100 Days in Appalachia. Click here to help support her reporting through the Ground Truth Project.