The LGBTQ youth in rural America faces a challenging environment. Some progress has been made in the last two decades, but many still feel threatened and unwelcome in their own communities.

Ray Saul spent years frightened for her safety at school.

She was outed as bisexual in eighth grade in Bardstown, Kentucky, a city of about 14,000.

“Someone overheard me talking to one of my very close friends, and then that person who overheard me told the entire middle school band,” Saul said.

From then on, she kept her sexuality and gender identity “under wraps,” she said, as the experience of being outed left her feeling threatened.

Saul is not alone in experiencing that fear. Things have improved in both rural and urban areas in the last 20 years since I came out while attending a rural high school in Eastern Kentucky. But the current environment for LGBTQ youth is still fraught.

Anti-LGBTQ hate speech is on the rise on Twitter, according to a media watchdog group. The American Civil Liberties Union reported that 2022 was the worst year on record for anti-LGBTQ legislation. And hate crimes, including the deadly attack in a Colorado Springs gay club in November, are on the increase.

I decided to see how some of today’s rural young people are navigating this difficult climate. Here’s what I found.

Frightened at Home and School

“My school is… very homophobic,” said Eros, a 17-year-old transgender and bisexual high school student from a small town outside of Knoxville, Tennessee. “There is less than a handful of teachers who are accepting.”

Eros, a pseudonym used to protect his privacy, is out to his mother but says that she is not supportive of his transgender identity. “She was OK with me being bisexual but was very adamant that I couldn’t be trans. She refuses to acknowledge my preferred name and pronouns.”

Eros has heard threats “here and there” from other students and feels that the rash of anti-LGBTQ laws and rhetoric from adults has emboldened people, including classmates, “to just be so outward about their homophobia and transphobia.”

“It’s scary,” he said. “Everywhere I go I’ve become constantly paranoid of everyone around me and what they might do.” Yet because of his parents’ lack of acceptance, Eros says he feels even more frightened at home. “High school, despite being discriminatory, is a minor escape for me.”

During Covid lockdowns, when many LGBTQ college students were forced to return home to hostile families, suicide prevention lines such as the Trevor Project reported call volumes “spiking to more than double” pre-pandemic levels. Twenty eight percent of LGBTQ youth have reported experiencing homelessness, the organization reports, while the National Network for Youth reports that LGBTQ young people have a 120% higher risk of experiencing homelessness than their straight and cisgender peers.

Growing up “Scared of My Identity”

A 2021 study by the Trevor Project found rural LGBTQ youth are more likely to state their communities are somewhat or very unaccepting of their identities and report higher rates of discrimination and physical harm.

One of those rural youths is 18-year-old Edmond Jeans, a first-year student at East Tennessee State University originally from the small town of Dandridge, Tennessee. “My family was incredibly unsupportive,” Jeans, who is transmasculine and uses he/they pronouns, said.

His family would not allow him to attend church as a child “because church was too liberal,” and his grandfather, Buddy Tucker, founded the infamous but now-defunct white supremacist group National Emancipation of Our White Seed, in the 1970s.

Because of this, he said, “I grew up kind of scared of my identity” and that his family “was trying very hard to keep me under their grasp.”

“There would be Trump flags and signs everywhere, even after he lost,” Jeans said. His birthday is on January 6, and he recalls the day of the 2021 insurrection as particularly frighting. “I was trying to shove myself deep into the closet, and the insurrection was happening, and I was just trying to ignore everything… and pretend I wasn’t real.”

Jeans ran away when he was 17 and was later put into foster care, where “I got two lovely foster parents” who happened to be a lesbian couple. “From then, I was unabashedly queer and trans.”

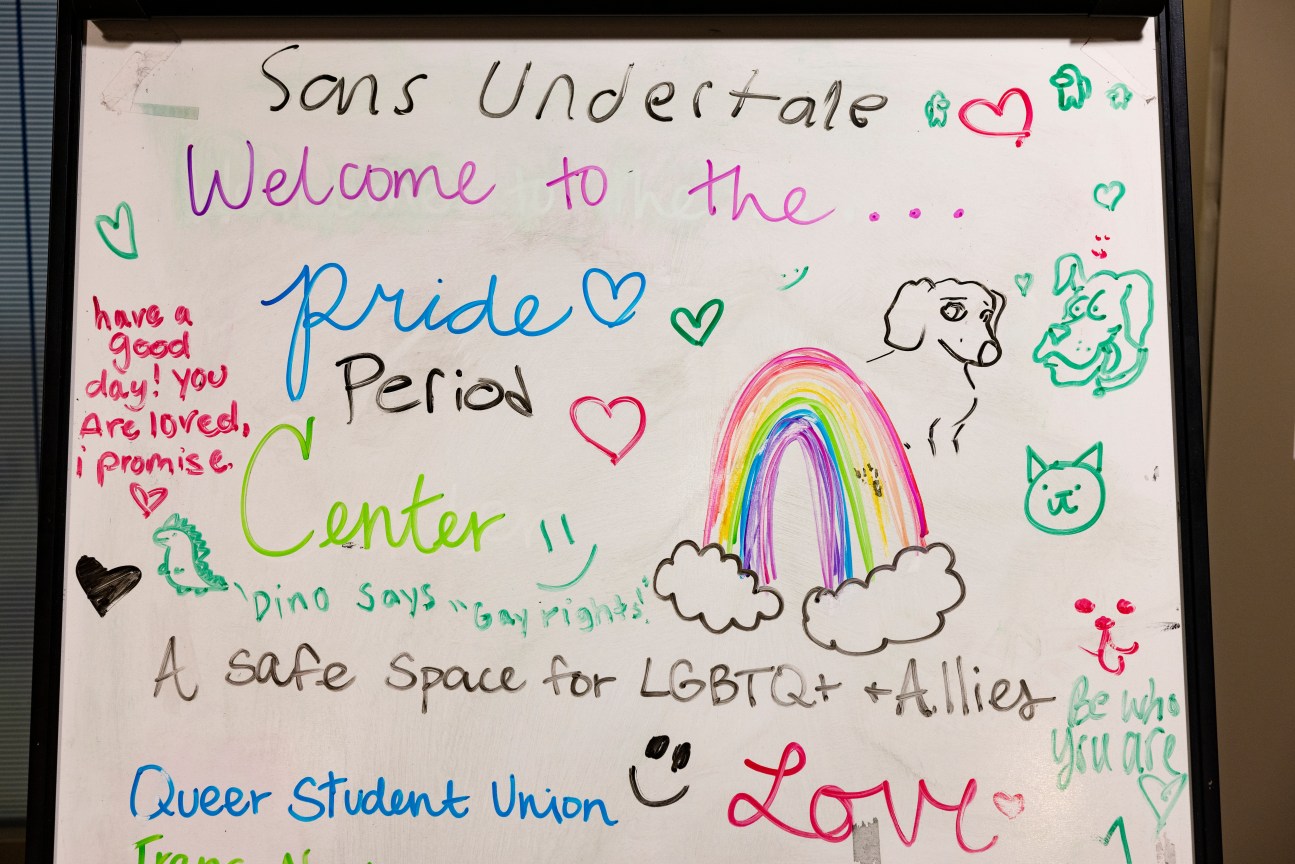

In August, he began studying at ETSU, a college in Johnson City (population 71,000), which attracts many students from surrounding rural areas. There Jeans found a vibrant LGBTQ community on campus.

“I’ve met a surprising amount of queer and trans people,” Jeans said. “We have a sexuality and gender alliance here, which is fun and lovely, and I love going to meetings and stuff because you can take a break. You can just enjoy existing as a queer person with other queer people, and it feels safe.”

Finding Someplace Safe

Finding community and safety at college is something many LGBTQ people, including Saul, can identify with. Saul, the Bardstown, Kentucky, student who was outed as an eighth grader, is vice president of the Queer Student Union at Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green. Now 20 years old, Saul identifies herself as “transexual and genderfluid.

Despite her experience, Saul said that Bardstown was not all bad for LGBTQ people. “When I knew someone was dating someone of the same-sex or someone else who was in the LGBTQ community, it was very much like, ‘don’t talk about,’” she said, but added that she did “feel like there was a touch of acceptance,” even if that acceptance was tacit and unspoken.

Like Jeans, Saul has found a supportive community on campus in the form of the Queer Student Alliance. And like ETSU, WKU is situated in a less rural setting (Bowling Green, population 72,000) but attracts students like Saul from surrounding rural regions. That means not everyone on campus is supportive.

“There’s still a lot of controversy with Western even supporting queer groups… because a lot of more conservative students or religious students are very much like ‘Western’s pushing this leftist agenda,’” she said. “I got a lot of hate whenever I did the WKU main Instagram takeover… some of the comments under there, before they were reported at least, they were very homophobic. Like ‘eww, a gay,’ and stuff like that.”

This escalated shortly thereafter, when Saul found the word “gay” scrawled on the side of her truck in a campus parking garage. There are no cameras in that parking garage, so the perpetrator has not been identified. Saul, however, feels that the university has responded to the incident as best they can and has felt supported by faculty and administrators. “I have a lot of university officials and professors that I am very close to working to see what they can do,” she said.

WKU Police, through a university spokesperson, confirmed details of Saul’s account to the Daily Yonder.

Despite the support she’s received from WKU officials, Saul still feels shaken by the incident. “Ever since that happened, I’ve been doing the buddy system. I’ve refused to go anywhere by myself.”

An Organization That Stirs up Animosity

Both Jeans and Saul have pointed to one organization – Turning Point USA (TPUSA) – which they blame for stirring up animosity towards LGBTQ students on their campuses.

“Turning Point makes it very apparent that they are not comfortable with us being around,” Saul said, pointing to the showing of the organization’s controversial film “What is a Woman?” as stirring up anti-LGBTQ sentiment on campus. “I just think it’s unfortunate that even though they are basically a registered student organization, and they have like a staff leadership… it’s just like they’re allowed to spread this type of hate and ignorance.”

Jeans, meanwhile, said that he has “become an enemy of TPUSA… I know there are individuals in that group who absolutely hate me and good, good, because I hate you too. You can hate what I stand for, which is human rights, and I’ll hate what you stand for, which is grinding people into the money machine.”

He also pointed to a showing of “What is a Woman?” as stirring up anti-LGBTQ hate on campus. The film was shown in The Cave, which is a vast public space in the student union on campus.

TPUSA says it has chapters on more than 3,500 campuses and is “the largest and fastest growing youth organization in America.” The organization’s website has a consistent anti-LGBTQ stance, including a section dedicated to articles with such incendiary titles as “Taking On The LGBTQ Cult” and “Banned From Facebook For LGBTQ Criticism.” The Human Rights Campaign has identified a Turning Point contributor, Frank Drew Hernandez, as one of the “top ten people responsible for driving the ‘groomer’ narrative on Twitter.”

TPUSA’s website says the organization’s mission is to “to identify, educate, train, and organize students to promote the principles of fiscal responsibility, free markets, and limited government.”

A Supportive Response

But there are other campus organizations that support LGBTQ students, including on campuses like hers that serve rural populations.

“In response to that film being shown… a bunch of other queer allyship type organizations came together and did an ice cream social in front of Cherry Hall earlier this semester,” she said. Cherry Hall is the flagship building of WKU, an icon of the university named after its founder and a gateway to campus – making it one of the most visible spots not just at WKU, but in Bowling Green.

Support for LGBTQ issues is not as uncommon in rural America some may believe. A 2019 study by the Movement Advancement Project found that between 2.9 million and 3.8 million LGBTQ people live in rural America, comprising up to 5% of the rural population and as much as 20% of the LGBTQ population.

This indicates that more rural LGBTQ people are choosing to remain in their communities rather than flee to larger cities, which in turn indicates increasing acceptance for LGBTQ rural Americans. A Gallup poll from earlier this year found a record 70% of Americans support marriage equality.

This has in turn translated into increasing support among rural representatives – including Republicans – for the rights of LGBTQ Americans. Thirty-nine Republican representatives and 12 Republican senators backed the Respect for Marriage Act, including several – like Elise Stefanik of New York on the House side and Cynthia Lummis of Wyoming on the Senate side – who represent heavily rural constituencies.

“More Open Mindedness”

“There’s been a lot more open mindedness in the Ohio Valley, by the river,” said 18-year-old Damien Cameron, a transgender man from Adena, Ohio. “When I came out as trans to my Boy Scout troop… they were all very conservative people. Like, they voted Republicans. They had Trump flags and whatnot. And I was afraid, but they were so confused. They were like ‘well, why would you think that we would think of you any different?’ And I was like, ‘wait a minute, this is not how it usually goes.’”

Cameron, who has identified as queer since he was in the seventh grade, said that having queer family members helped him come out. “I had a strong support network that made it easier,” he said.

Still, it was not all easy. Cameron experienced anti-LGBTQ bullying in a private school he attended. He attributes that to the privilege of the wealthy students there. He found public school “more freeing,” but not as accepting as he would have liked. After making friends with other queer students, they began petitioning for a queer student alliance in their school.

“We wrote like a whole petition, and the principal just sort of turned it down,” he said. “I’m from a very conservative area… and so, I definitely have an understanding of why he was hesitant. Because he was a supporting-enough guy. It wasn’t out of malice. I think it was out of fear for the reactions that parents might have, or other students, or people on the board.”

Whether there would have been a significant negative reaction to the start of a queer student alliance, Cameron said, is “hard to say.”

More to Be Done

The amplification of anti-LGBTQ sentiment has consequences for LGBTQ youth living in rural America. When asked what he would say to policymakers pushing anti-LGBTQ bills, Eros said “I would tell them how scary it can be.” Seeing his friends “get harassed on the day to day just for being themselves” has put him under a profound amount of stress.

Jeans at ETSU also lives in a state of heightened anxiety. “I have to look at the broader world and see if I’m in danger,” he said, referring to an upcoming event he was attending at an LGBTQ coffeehouse in Knoxville. “It almost feels dangerous to have this Merry and Gay Market because if people are going to attack, they can see, well, that’s where they’ll be. If it’s the Merry and Gay Market, that’s where a bunch of them will be congregated. And it sucks that I have to be scared about that.”

Skylar Baker-Jordan is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in The Independent, Newsweek, Business Insider, and elsewhere. He is contributing editor for community engagement at 100 Days in Appalachia and currently lives in East Tennessee.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()