Driving on Route 329, near Athens in the spring is a welcome respite after another long COVID winter. The grass on southeast Ohio’s rolling hills is turning that bright-almost-neon shade of green. I’m on my way to visit Ada Woodson Adams, a historian and activist who has spent decades working to preserve the Black history of Athens County.

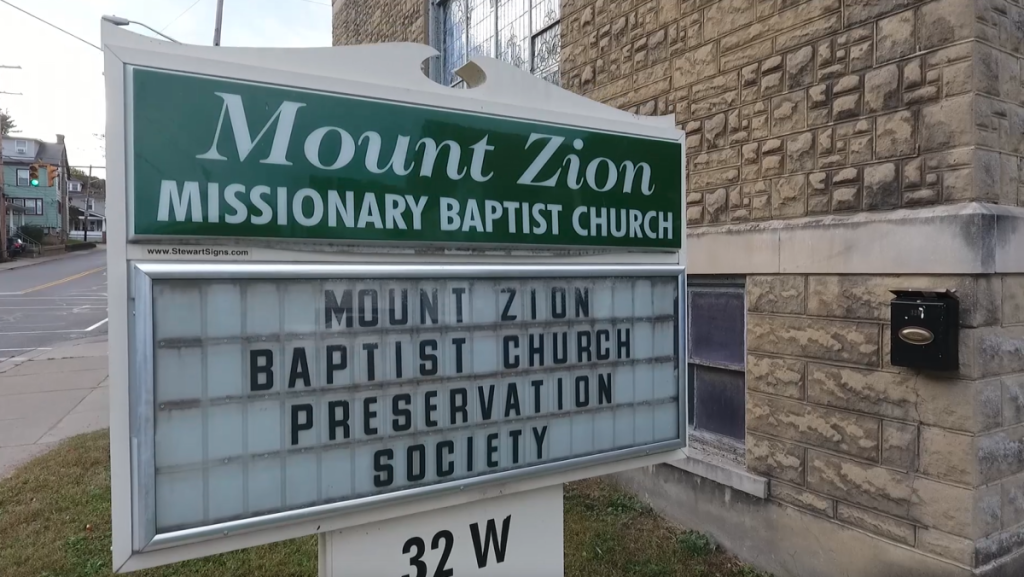

Woodson Adams is president of the Mount Zion Baptist Church Preservation Society in Athens. The church is the last major structure still standing in Athens County that was built by the Black community. It’s a stone’s throw from Court Street, the center of this college town and the place where OU’s students spend much of their time.

I arrive at Woodson Adams’ home, where we sit at her dining room table over coffee and toast. Mount Zion, she said, has been an important part of her life for decades.

“I was baptized, and eventually married at Mount Zion.” But she was quick to point out that the Black church has always been more than a religious space.

“The church was always a strong part of the Black community, and not just for religious purposes,” she said. “Many went there to get centered, to reconnect with their cultural upbringing.”

She also said that for her, First Baptist Church in Nelsonville where she grew up, and Mount Zion in Athens were places where Black people developed their identities as citizens. “In public, Black children were to be seen, not heard,” she said. “But at church, we could develop and express our opinions.”

The Black Church has always been a place where the Black community could be themselves and have agency in articulating that voice.

Mount Zion was built in the first decade of the 20th century, and it served the Black community until the early 2000s. It now stands vacant and in need of several million dollars of restoration work. An April storm shattered one of the church’s stained glass windows, scattering shards of glass on the sidewalk.

For Ada, saving Mount Zion is a reminder that in a democracy everyone’s experience is important. “One of the things about a democracy when it’s working right, is the people’s voices are being heard,” she said.

Dr. Tee Ford-Ahmed directs communications and media for the Mount Zion Baptist Church Preservation Society. She is certain that Mount Zion Baptist Church would have been torn down without the efforts of the Athens community to save the building.

“Here we were in Athens where the Black American story was about to be totally erased,” said Ford-Ahmed. “With just one building standing that represented over a hundred plus years of history.”

Such fears are based on her own experience and the fact that the two other significant public structures in Athens County built by Black people are gone.

The Albany Enterprise Academy was built in the early 19th century to educate Black children in the area. It was torn down in the 1880s.

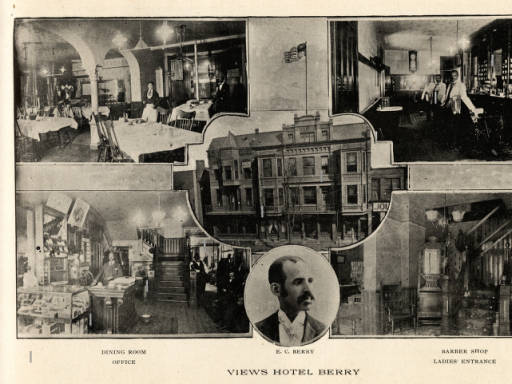

One of the academy’s graduates, Edward C. Berry went on to build The Berry Hotel in downtown Athens, on Court street. He and his wife owned and operated the hotel from 1893 – 1921.

The Berry was a state-of-the-art hotel with a national reputation. Notable guests included President Theodore Roosevelt and Elizabeth Custer, wife of General George Armstrong Custer. It had an elevator, electric lights and was the first hotel to include a bible in every room.

The hotel was torn down in 1974 to make room for a parking lot. A diner now occupies the space where The Berry once stood.

Ford-Ahmed said the destruction of Black-built structures is a cycle she has lived through before. A church she attended in Charleston, West Virginia, was torn as part of that city’s urban renewal efforts.

“It was torn down to accommodate the post office,” she said. “I’m beginning to see, ‘Oh my goodness, yes.’ There is a pattern, a pattern of Black erasure.”

She sprung into action to keep Mount Zion from a similar fate. The Mount Zion Baptist Church Preservation Society decided to produce a series of short documentaries to tell the story of the buildings in Athens County that are gone; and the one, Mount Zion, that remains.

The first episode of Athens: Black Wall Street debuted in February at the Athena Cinema in downtown Athens, a half block away from where The Berry Hotel once stood.

Producing the film led Ford-Ahmed to the Athens City School system.

She worked with a group of teachers and the superintendent of schools to have the documentary screened at the local middle and high schools.

“Every teacher showed it to their classes,” said Athens high school principal, Chad Springer.

He greeted me in the high school’s public entrance, flanked by school trophies and administrative offices. As we sat down in his office, Springer said that showing the documentary at school wasn’t about a political agenda.

“No matter what side of the political spectrum you’re on, making educated choices is the best,” he said. “We are just making educated voters.”

Part of that, he said, means learning from history, to understand, in his words, “what got us to where we’re at now.”

Principal Springer told me he has not received any complaints about showing the film from parents.

School officials also worked with Ford-Ahmed to develop the “Saving Places Challenge.”

To participate, students could write an essay, construct a piece of visual art, or create a social media post that described a place that was special to them, and how they would feel if it were to disappear.

18-year-old high school senior Braxton Springer was inspired by the documentary to take part in the challenge. Braxton and I sat down in the Athens High School Library to talk.

“I’ve lived here my whole life,” he said. And I didn’t know about the Berry hotel until that documentary.”

“When I heard about the Berry hotel and the way it got torn down, after being there for so many years, it inspired me to really just create my own structure in my own room.”

I asked Braxton about the connections between Black History, his project, and the fact that he will vote for the first time this year.

“I think listening to the history is what brings us together,” he said. “If we listen to anyone’s story, it automatically strikes us in our heart.”

Braxton said that he is more likely to vote because of his expanded understanding of southeast Ohio’s history.

“I think we have more of a choice to decide what happens in our future generations and what we can do in order to, you know, make our voices heard,” he said.

For Ada Woodson-Adams, the efforts to preserve and document her region’s complete history holds important lessons for the state’s political leaders.

Mount Zion can teach, especially the state legislatures that it’s better to work with the people than against them,” she said. “Mount Zion represents what we would like democracy to be.”

This story is part of Disconnected Democracy, a collaborative project of the Ohio Newsroom, a partnership of public media newsrooms across Ohio. In a time of polarization, we’re asking Ohioans what matters and searching for what connects us. Find more at www.wksu.org/disconnecteddemocracy.