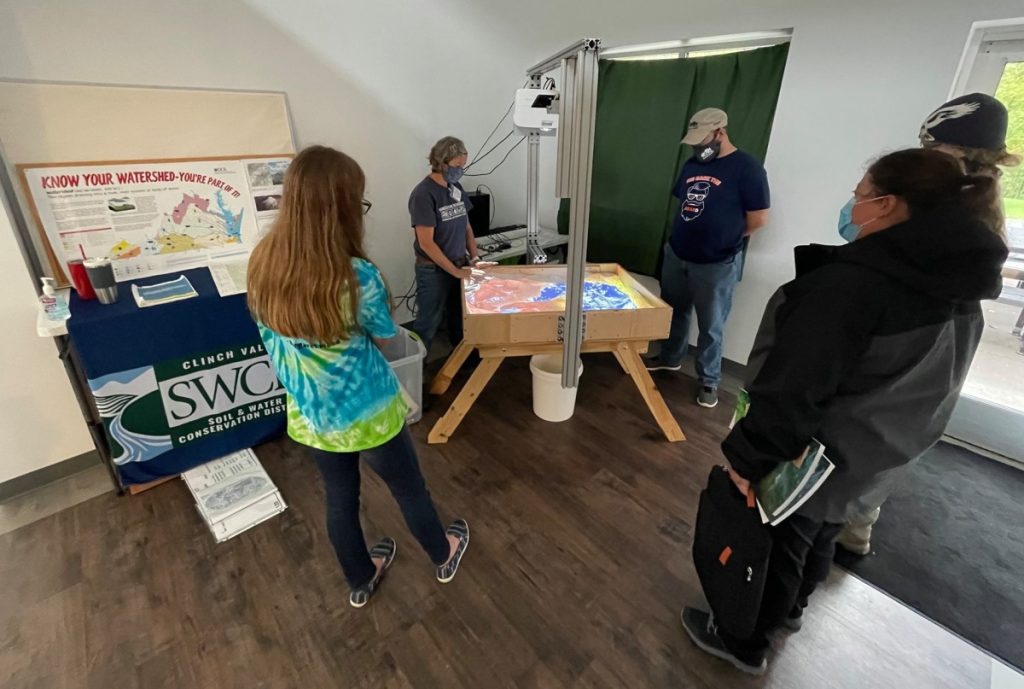

Fog obscures the Clinch River on a Saturday morning this past October, as a group of educators gathers at St. Paul, Virginia’s Matthews Park. Shortly after arriving, part of the group moves to the riverbank, discussing how to tackle pollution from illegal dumping into the waterway. Another huddles around an augmented reality display, sharing how various land use practices trigger water pollution. Still another heads across to the community’s downtown nearby district to tour a local museum’s exhibits on the fraught social history of Virginia’s coalfields.

For the past decade, my colleagues and I have hosted this annual symposium for rural educators in St. Paul in southwest Virginia. The event has a single goal: train Appalachian educators how to use local issues and case studies as lessons in their classrooms.

Research shows rural students often best connect with complex concepts when those concepts are framed in relevant cultural issues, and the coalfields of Central Appalachia are ripe for adopting such an approach. From environmental degradation to economic decline and Appalachia’s many hot-button social issues, there’s no better classroom than our students’ everyday lives.

In recent weeks, however, Virginia’s educational philosophy has been turned on its head. Governor Glenn Youngkin has made education reform a goal of his tenure.Youngkin and legislative officials are implementing measures to curb the use of so-called “divisive concepts” in Virginia’s classrooms.

State officials’ proposals, most aimed at the oft-maligned yet ill-defined Critical Race Theory, have been less carefully-crafted policy examinations and more sweeping attempts to quash the discussion of social issues known for courting political controversy. Youngkin’s office recently set up a tip line, for example, that encourages parents to report educators “behaving objectionably” not to school officials but to partisan interests in the state Capitol.

Meanwhile, other Appalachian states have chosen similar paths. Several have introduced or passed legislation similar to that proposed in Virginia, seeking to ban certain topics from classrooms and penalize educators who use them. McMinn County, Tennessee, sent shockwaves through the literary world in January when its school board unanimously voted to ban the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus, which focuses on the Holocaust. And northeast Tennessee’s Sullivan County recently fired one of its teachers after a discussion of systemic racism in a Contemporary Issues class generated complaints from parents.

These political incursions into classrooms should be concerning to everyone, but they’re especially alarming here in Appalachia. Rural educators already teach within reduced support structures, with the pandemic stressing serious cracks in our educational system. Many educators have therefore been increasingly harnessing socially-resonant curricula to engage students during a time when we have all been rooted closer to home. The chilling effects created by states’ vaguely-defined content bans will further shrink an already reduced arsenal of resources at educators’ disposal.

But beyond those immediate concerns, there’s a more fundamental reason why Appalachian residents should be wary of efforts to curb the discussion of thorny social issues in classrooms: For generations, our region has been a living laboratory displaying why those kinds of issues can be such effective teaching tools.

A half century ago, northeast Georgia’s Foxfire program — started as a writing project to engage students with local history and culture — led the way, with students chronicling subjects like the illegal moonshine trade and assembling detailed moonshine recipes alongside blueprints for building a still.

In eastern Kentucky, Appalshop’s Appalachian Media Institute has for decades helped local youth produce documentaries tackling topics from the region’s opioid epidemic to Appalachian LGBTQ+ experiences.

And more recently, high school classrooms in Appalachian Ohio have formed teams to address climate change in part by advocating for local officials to adopt climate-conscious policies. Similar examples occur daily in untold hundreds of regional classrooms, helping rural Appalachia blur the boundaries between schoolyards and our broader world.

If this history has taught us anything, it’s that our communities and our students are best served when educators are free to embrace creativity in their classrooms and, yes, confront uncomfortable issues. And one needs to look no further for direct examples of community impact than the group that gathers each year in St. Paul.

Those educators have taken their work to the next level by empowering students to critically examine their own roles in contributing to and repairing societal problems — the very approach that many states are now attempting to prohibit. Some have used the approach to tackle generations of environmental neglect in disadvantaged communities, assisting with the cleanup of nearby waterways. Others have converted an eyesore of a town dumpsite into an award-winning outdoor learning center, serving community members of all backgrounds and ages.

In fact, there’s an argument to be made that the coalfields’ youth are taking a leading role over even our government officials in tackling the region’s challenges, thanks to the ingenuity and fearlessness of the educators guiding them.

Increasing parental choice in public education is often touted by officials as the motivation behind their reform efforts, and that’s a topic that should be part of policy discussions both locally and nationwide. But how those efforts are currently manifesting — proposed bills that criminalize educators’ use of controversial topics, tip lines asking citizens to report their neighbors to political officials — is not a debate about parental choice. It is a co-opting of the public education system as the latest skirmish in a culture war that is increasingly hindering our nation’s ability to collectively solve complex problems.

As legislatures careen towards censorship in the classroom, elected officials must realize that their actions will resonate far beyond the current election cycle. Students trained to view discussions of controversial issues as taboo or even illegal will carry those attitudes into adulthood, further hobbling our society’s efforts to solve shared problems.

Those students may enter colleges and universities — places where confronting controversial topics is a daily expectation — ill-prepared to succeed in the next phase of their academic careers.

And our rural communities will suffer, lost in the flawed assumption that our youth are too fragile to handle the issues that our leaders seem too preoccupied to confront.

Wally Smith is an Associate Professor of Biology at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise and works with educators across central Appalachia to develop place-based curricula for rural schools. The opinions expressed in this piece are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of any other institutions or organizations.