The Buffalo Creek Flood killed 125 and scoured away the homes of more than 4,000. The 50th anniversary offers a chance for those who were affected — directly and indirectly — to mourn the loss and celebrate what endures.

“… And Father God, we thank you for this occasion. Even in the Holy Scriptures you encouraged your people to always remember, remember the sacrifices of those who had gone on before them. Remember their history lest we be doomed to repeat it. Remember those who struggled and those who lost lives and loved ones and some even here today. We have never gotten over it. We’ve learned to live with it because we know that your grace is more than sufficient, but we will remember them every day of our lives. And we pray, oh Father God, for those who are still bearing scars, emotional scars, mental scars.

Even though it’s been 50 years, many still remember it as if it was just yesterday. But we know, Lord God, you love us all. You love us all red, yellow, black and white, male, female, rich or poor. We’re all precious in your sight.”

Rev. Mike Pollard, invocation

at Buffalo Creek Disaster 50th Anniversary Ceremony

The thing about being married is there are some mornings you wake up and know you aren’t going to get to stay home and watch the ballgame. We have a rule at our house that comes from something my grandmother said. When my parents got married in a big 1950 wedding in the Presbyterian Church in Hazard, Kentucky, my Popaw, also named Dee Davis, skipped out and slipped off to Tennessee to go fishing. Granny said, “Don (her teenage son) had to walk me down the aisle like I was some old widder woman.” I am an OK husband at best, (be careful what you get good at), but even I know being married means there are some days, some places where she does not want to show up looking like an old widow woman.

February 26, 2022, was the 50th anniversary of the Buffalo Creek Flood in West Virginia that killed 125 people and left 4,000 homeless. Mimi Pickering, my wife, made two documentary films about the disaster. The first is Buffalo Creek Flood: Act of Man. That film was selected for the Library of Congress National Film Registry in 2005. Among the 25 American films selected that year were Toy Story, Giant, Cool Hand Luke, and Rocky Horror Picture Show. Mimi also made the documentary Buffalo Creek Revisited, which focused on community efforts to heal and rebuild 10 years out from the flood. Both films were produced at Appalshop, the Appalachian cultural center in Whitesburg, Kentucky, that brought the two of us together, artist and arts administrator.

And what happened on Buffalo Creek in 1972 was far worse than a rocky horror picture show. It was an American tragedy. After days of rain and wide-spread foreboding that the Pittston Coal refuse dam up the creek might fail, company representatives assured people in the small towns like Saunders, Pardee, Lundale, Amherstdale, Accoville and Craneco that the dam was sound, and all was well. But at 8 a.m. on Saturday morning the dam collapsed releasing a tidal wave of water and sludge that crushed houses, cars and a way of life that stood in its path. Sixteen coal towns along 18.8 miles of creek smashed.

I am writing this not as journalism or as history. I don’t have much to add to the record, and there is a lot already in old Beth Spence columns in the Logan (County) Banner, books by Gerald Stern and Kai Ericson, Mimi’s films. The history in broad strokes is that the coal company was negligent, the regulators failed, Governor Arch Moore sold out the valley signing a one-million-dollar settlement the week before he left office. There was outrage over the corruption and outrage over the suffering and deep unrelenting depression over all that was lost. Buffalo Creek is where we first heard “PTSD” as a way to describe what happens to us when we endure intense trauma. The class action suits brought on behalf of residents in those 16 towns downstream changed the laws and the way law is now taught in universities. Even the company sucks who always defend the industry and blame others can’t dispute the facts of that day. They can only wait for us to forget.

The brief and officially sanctioned passage in the West Virginia high school history book says: “The flooding of Buffalo Creek, a tributary of the Guyandotte River, in February 1972, resulted in the loss of at least 118 lives and caused many West Virginians to demand that flood control measures be taken by state and federal governments.”

Other than that Mrs. Lincoln, how did you like the play?

So, this is not about facts. It is about being a hillbilly, about what we witness, a little about making movies, and my advice on marriage.

No one sets out to revisit a tragedy with a light heart. Saturday was going to be a two-hour drive to have your revery crushed. But we tried to make the best of it, joked around, laughed at the two senior citizens we have become.

You know how old you are when stopping in Pikeville for biscuits is a road-trip highlight. We talked about the grandkids and when we’d see them again. And we listened to music on the satellite radio chatting about bands and biscuit places we had appreciated. There was a moment when the Band’s song “Up on Cripple Creek” came on and I got a good chuckle because a friend always describes my marital relationship with lines from the song:

Up on Cripple Creek she sends me

If I spring a leak, she mends me

I don’t have to speak, she defends me

A drunkard’s dream if I ever did see one

Once in Man, the town where Buffalo Creek empties into the Guyandotte River, we headed to the high school. Good crowd. We had to park out on the road across from the fire station. We got to the school about 10 minutes before the scheduled start, assuming it would not begin early. Mimi is making a radio show out of the event, so we went in the back and a former teacher, Billy Jack Dickerson, knows who Mimi is and showed her where to plug into the patch panel. I grabbed two seats in the front row and waited.

Though I had never been to Man before, since I grew up in a coal town, I felt like I knew it, and I had lived with the Buffalo Creek films. Also, the first girl I really kissed was from Man. She had cousins in Hazard. I think her name may have been Patty. She was also the first Italian girl I ever met. Good times.

Man High is home of the Hillbillies, which is pretty cool. Several of the speakers on Saturday made a point to say they were proud to be a Hillbilly. Members of the current Man boys Hillbillies basketball team sat along the wall beside me, prompting one of the politicians on stage to tell the players to bring the trophy home next month.

The other thing about Man High was that instead of using a likeness of noble mountaineer as their mascot, or some Snuffy Smith-looking cartoon scalawag, the symbol for the Man Hillbillies is that of a goat. That goes back to the original insult, which intended to say mountain folks were half people, half billy goats scrambling over these hills. Why not embrace the symbology and spit in your detractor’s eye? If you are going to be a bear, be a grizzle. If you are going to be a Hillbilly, be a Capricorn. Let who you are be somebody else’s problem. Butt ’em.

This memorial ceremony started like a lot of small-town gatherings: People touching each other on the shoulder, especially glad to see one another after years apart and Covid distancing. The hall filled slowly. The master of ceremonies did not know it was going to be his job until just before, as he kept explaining to remove no lingering doubt. The school color guard marched to the front with flags and white plastic rifles; one lovely girl with a gun and a ring in her nose was face-to-face with me as we all said the pledge. The Reverend Pollard, one of the few people of color at the event, delivered the invocation after first explaining he was listed on the program as the benediction, but that he switched because he had a funeral in Madison to preach, and he was going to be late for that, but he could not miss this moment. He said on that day in 1972 he was just back home from his deployment to Southeast Asia when word of the flood hit the news at his base in Kansas City. There were no working phone lines on the Creek, and he got an emergency leave to drive home in his VW “beetle bug.” He said that 17-hour drive back to Buffalo Creek was more frightening than any of his time in Vietnam. He walked off the stage leading the room in singing “Amazing Grace.”

Also on the program were proclamations from the state Senate and House of Delegates. Representatives from Governor Justice’s office and from Senator Joe Manchin read letters. Senator Shelley Capito, Arch Moore’s daughter, did not send greetings, but that was probably discretion’s better part of valor. One modern moment came when a 50-year-old college student called in via video from Brooklyn. His mother had perished in the flood getting him, a newborn, to safety, and he talked about his dad raising him alone as the MC held an iPhone up to the mike.

There was a PowerPoint presentation next from a graduate student at West Virginia University. She had spent a good deal of time documenting the event with families there and had created an online memorial. Mimi had seen it and said it was powerful. And now I will say something ungenerous. PowerPoint is the sworn enemy of storytelling. I do not understand why academics and business people use it. Do they think anyone from an audience has ever returned home with a bar graph or a pie chart etched in memory? The overhead projector shut itself off three times during this poor student’s presentation, each time taking minutes to reboot. And when it went down on her last slide, she concluded, only to have that slide pop back up on the next person’s presentation and stay up.

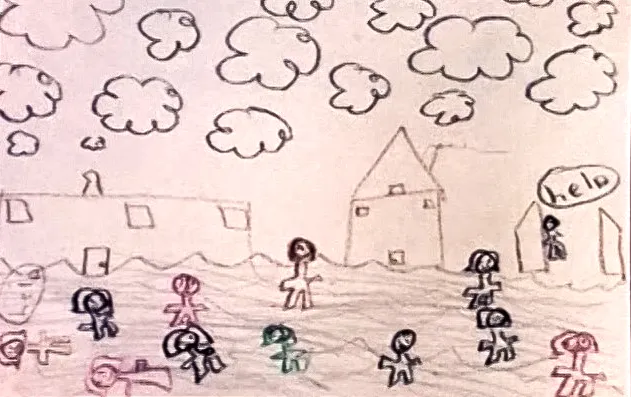

That next speaker was Billy Jack Dickerson, who retired in August as Man High School science teacher. He talked about an environmental science course where a computer program randomly assigned him a class of 16, all girls. The idea was to teach chemistry, physics and biology to undergird what students would need to know to understand natural disasters like hurricanes and tsunamis. But he discovered that the students in the class had no knowledge of the Buffalo Creek Disaster that changed everybody and everything in 1972. So he made it their mission to remember for the community what he could never forget.

We lived just on the alley below old Lundale Grade School, and I know some of you know where that was, past tense, was. And when I was just an infant, Lundale School was still operational. And the reason that I know that is there are pictures of my parents holding me out in the alley. We didn’t have streets, we had old red dog alleys and God knows whatever else, whatever Amherst or whichever coal company could dream up and Jimmy Chandler would come down with a grader every now and again and grade it down to the point that you might be able to drive over it.

And I can tell you from experience, if you ran and fell on it as a kid, you would wind up with stitches. I speak from experience. That stuff [red dog, a coal waste product] is sharp. And I fell one time, just as a side story, and cut my eye down. There’s a scar under these. John L. Lewis is what my mother used to call them, eyebrows that I have. And there’s a scar under there that took 10 yards of catgut to sew up from falling on a red dog alley right there in Lundale.

But our house faced up the creek. Bart Brunty’s house faced down the creek. And our houses were so close together you could throw a rock with not much of a toss. It was back door to back door. And on the morning of the Buffalo Creek Disaster, flood, whatever term you like, we were sitting there like many young kids watching cartoons. Cartoons were a treat in those days. They were not on 24/7. There was no such thing as a Nickelodeon, and my kids are so old, one of mine’s sitting there holding my granddaughter and she’s 30 so I don’t know the cartoon protocol anymore. CoComelon on my phone. That’s what I know now.

But we were watching cartoons, still in our pajamas and lights flickered. And you’ve heard this similar story told time and time again because it happened for so many people. The lights flickered and I guess probably one of the things that saved us was the fact that our house did face upstream so we were able to look… I’m saying the collective but primarily my mother looking out the front windows and seeing the creek itself just rumbling higher than it’s ever rumbled before and all this debris. …

I can still hear the words of my mother saying, “Boys…” I have two other brothers. One was seven at the time, and my youngest brother, Jack, he was 13 months old. But she was talking to me and Darren and said, “Boys, get your shoes on, something’s going on.”

You lived in those old coal company houses and one of the things that you always did was keep a pair of shoes by the door because you never knew when one of the those things … They were a fire waiting to happen, so you kept shoes by the door. Unfortunately, I didn’t have any there but my mother had a pair of… Ladies, some of you are old enough and it’s OK, to remember gold lamé house shoes. Very thin-soled. I wore those bad boys out proudly. That’s what I wore out of the flood. They kind of looked like elf shoes, little pointy-toed deals. They didn’t match my flannel pajamas at all, but that’s what I had.

And I’ll never forget, as we walked out the front door in a hurry, we looked up and again, for those of you that remember: Upper Lundale and Lower Lundale were divided by the Amherst [Coal Company] offices, the post office, and the store, and then that big row of hedges there. Y’all remember them? And that’s where it was when we cleared the front gate was at that row of hedges.

And I’ll never forget going across, going right handed toward the railroad tracks and getting to the first set of tracks. There were three. Getting to the first set of tracks and it’s getting closer. And the leading edge is already coming so by the time we go over the hump of the first set of tracks, we’re wading water. And we go over the second set and we’re wading more water.

And we get past the third set of tracks and there were men standing there, maybe some of you men were standing there helping my mother as she reached my brother, 13 months old, up the hill. Not a very big hill at all, probably as high as this wainscotting here at its maximum height. And as soon as we got up to that elevation we turned around and our garage was already gone. And we climbed a little higher and we turn around and I can still see this image of our house just tilting backwards and going away.

Everything we owned, everything we thought about, everything all in one motion, changed forever. And I still see that 50 years later. It’ll forever be burned into my brain. And the sounds of my mother and the sounds… And again, take it all in. And I was forced to. I ask you guys to do that. I ask you to use your senses to embed those things in your brain, and I had to do it, not voluntarily, was forced to do it.

And we stood there huddled together on that hillside… Where you at, Eddie? Any of you that know where Eddie used to live? You live there now? That’s where we stood. That’s where my dad gardened. That’s where I picked 9 billion rocks out of that garden as a kid. My dad thought it was a pastime. Like I didn’t have anything else to do, couldn’t ride my bike or have any fun. “Go pick rocks out of the garden, son.” I could go on and on. No, I didn’t get them all. I guarantee you I didn’t get them, Eddie. No, good Lord.

But that’s where we stood and watched our life go away and change forever. I know a few of you were standing there with us. How many [he asks the audience]? We stood right there. I see those hands. And we stood there having no idea whether anybody else on the planet was alive because we didn’t know what happened. Had somewhat of a clue.

And miraculously my dad, and I’ll use the language of the day, was a car dropper at Amherst #2. And he literally ran from Dingus Holler along different tram roads until he could get down to where we were. Golly Molly. My dad is 83 now and is not long for this earth. But he ran like a wild man and when he got to us, he fell on his knees, and I haven’t seen my dad cry very many times, but he cried like a baby because we’d made it, we had survived it. Oh, good Lord.

Billy Jack Dickerson

And here I want to say in my time I have witnessed great oratory and amazing performances. I advanced Jesse Jackson’s Super Tuesday speech in Memorial Gym in Hazard in 1988, and I sat in the Boston Garden rafters for Obama’s “I don’t see red America, I don’t see blue America” keynote in ’08. I watched Traveling Jewish Theatre’s legendary presentation of The Last Yiddish Poet in Whitesburg, and I saw Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart perform Waiting for Godot on Broadway. One night in Philadelphia in 1986 Grover Washington Jr. joined a delegation of a dozen of us and said he wanted to give us a gift. He then played Duke Ellington’s “Sentimental Journey” on the soprano sax. I was two feet away. But none of that was like being in the Man High School auditorium on the front row that Saturday. Nothing ever as urgent. Nothing as true.

Billy Jack explained that he made it out, but James who sat beside him in class that year and April Ellen down the hall were taken in the flood. “It was kind of hard on a 10-year old.”

Then like teachers do, he asked for a show of hands. “How many of you are survivors? Hold them up high, folks.” Then there was this moment of recognizing each other among old faces. “You ought to be proud. Man, it’s good to see you all.”

He closed saying: “I sit and I think who would I have been? Would I have been this guy that you see standing in front of you today? I don’t know. My location changed. My friends changed. My school changed. My everything changed, and clearly so did I. Who would I have been? Hard telling. Hard telling. But this is who I am now. I’m this guy.”

After the auditorium we all went out front where a student played taps as 125 helium-filled balloons with messages like “we will never forget you” were released into the winter sky. There was a big meal for everyone in the cafeteria, miniature wieners, meat balls in bright red sauce, four kinds of potato salad, and sweet tea in Styrofoam cups. People talked tenderly with each other. In ’72 after the flood, those with no one to take them in had to live in the high school, take their meals in this same cafeteria. Mimi pointed at the spot where she interviewed the man who said, “I’m sorry that God let me live to see it.” He had just gotten his children to safety, then watched 14 houses and five cars full of people destroyed when they hit the bridge. He counted.

Mimi said upstairs in the classroom above us is where she interviewed Shirley Marcum, who said, “I didn’t see God a-drivin’ them slate trucks and wearing a hard-hulled cap. I didn’t see that at no time.” Shirley is the person who said she did not believe the flood was an act of God. “It was an act of man.”

When we left, I pointed out the large modern fire station by the school. I said, “Look how big that place is. Remember that guy in the Charleston Gazette who said the money we raised for Buffalo Creek Revisited should have gone to buy a firetruck?” She said she did not remember. That stunned me. Hard to be a hillbilly if you can’t hold a grudge for 40 years.

She said, “Do you mind if we drive up the Creek?” The companies owned all the land. Early days they put miner housing along the creek bank in the flood plain. The initial post-flood recovery plan was to rebuild communities in suburban style nodes, public housing where four dwellings were combined in wings like a windmill blade lying flat and painted yellow. A few of those yellow buildings are still there. But most of the homes are stuck back cheek and jowl where the coal camp housing had been, a lot of them prefabricated or trailers. A second tragedy was how long it took people to get home and then how hard it was to find community among the survivors. Mimi pointed out places remembering lines and voices from the films, “That’s where Gail Amburgey lived. She said ‘When you forget, that’s when you go crazy.’”

She showed me where Ruth Morris lived. My favorite line in all hillbilly filmmaking is Ruth saying, “My next-door neighbor would take my carburetor and put it on his car. I’d take his tires off and put them on mine. That’s the kind of neighbors we was. We didn’t run knock on the door and say, ‘Can I do?’ We went and walked in and did do.”

We drove up past Accoville and Lundale to Pardee and Saunders where the houses had not been built back. We passed coal trucks and miles of conveyor belt. Through most of Appalachia the coal industry is dead or necrotic, but there is high quality metallurgical coal on Buffalo Creek and Coronado Coal, based in Queensland, Australia, is actively mining it. We drove to where the dam broke. Not a lot to see now. A giant tipple. Water coming out in a controlled cascade. Mimi quoted another line from Ruth, “Well, they was all back to mining five days later, if you’ll just read your papers.”

Driving out we noticed a historical road marker that does say Buffalo Creek was one of the worst floods in U.S. history caused by ignored safety practices. And it said the flood released a 130 million gallons of black water, killed 125, and left thousands homeless. It’s there on the sign, if you slow down.

It had never really occurred to me before that drive just what it meant to be so young and untested and at the same time entrusted with making a film about enormity. Mimi was a college freshman when she showed up in West Virginia. She came from what’s now called Silicon Valley. Her mom had been a Stanford journalist, and her dad sold insurance. She had already been to Europe twice, the second time hitchhiking on her own after she graduated high school early. She was 19. I have T-shirts in my drawer older than that. She took on the responsibility to record, edit, and remember an American tragedy for people who in 1972 were mostly looked on by the rest of the country as War-on-Poverty pitiful or sitcom jokes.

Mimi was not a survivor like the Buffalo Creekers who’d witnessed the water crush their neighbors and their communities, but just the same she had their story to tell. And that’s a burden to bear too. It took several years to raise small sums of cash for film stock and processing. The hard part in making documentaries is hanging on. It takes time to find the stories, sync the pictures, and understand it all. You gotta eat. The two top funders for Buffalo Creek: An Act of Man were 1) the Kentucky state unemployment office, which helped Mimi navigate the stretches between paychecks, and 2) the Imperial Club, a roadhouse across the county line in Vicco. I met Mimi when she was making her film by day and waiting tables at the Imperial, which catered to after-work coal miners and occasional biker gangs. “Keep the change, darling.” Vicco was not Palo Alto.

Like a lot of the residents on Buffalo Creek who had endured the flood and were trying to find a way forward, Mimi was not practicing conspicuous self-care. Budweiser, Jameson, Marlboros, diet pills to get going, downers to ease off. Her work clothes were hot pants and snug T-shirts. She was the kind of girl your mother always warned you about, and the one you drove from beer joint to beer joint longing to find. Mimi had that thing that made men want to leave a gratuity.

Now she is a lovely grandmother who talks to me about biscuits. “Wasn’t there a Tudor’s Biscuit World in downtown Louisville at one time?” She spends her days working on radio documentaries and access to birth control for hillbilly girls. She’s chairman of the board of Appalachian Citizens Law Center, which fights for miners with black-lung disease and against coal-company-caused environmental hazards. And in the evenings when I am having a drink and watching a ballgame in the living room, she in the kitchen on video calls seeking justice and reconciliation for people she will never meet. Ever. She was a Guggenheim Fellow, a two-time Kentucky Arts Fellow, and they teach her work at colleges including the one she dropped out of to make The Buffalo Creek Flood. She still gets fan letters from law schools. She turns 70 next month. I don’t know who she would have been, if her path had been a little straighter, smoother. Or if she had married somebody better at the job. Hard telling. No matter. The thing you learn being together long enough is that there are some questions you leave unasked.

This article was originally published by the Daily Yonder.

Dee Davis is publisher of the Daily Yonder and president of the Center for Rural Strategies.