As an Appalachian who is painfully aware of our history, I found it took some nerve for Conor Sen to write in all seriousness under the headline “Amazon’s New ‘Factory Towns’ Will Lift the Working-Class” in Bloomberg last week.

Many of us have watched as chain stores like Wal-Mart, Dollar General and Family Dollar have become the largest employers in our communities, replacing the extractive industries of our past. But those jobs don’t come with the same pay and benefits that workers need to survive.

Giant companies like Amazon, Walmart and Dollar General are the employers with the highest rates of workers on federal and state aid programs – making up as much as 3 percent of all recipients in some states. This low pay and the assistance employees receive in the form of SNAP benefits, or food stamps, requires them to work, shop and live in the shadows of these supercenters, reminiscent of the coal and mill towns that once stood in their place.

So when Sen’s piece about Amazon appeared in the national news as a full-throated defense of the company town, I had to chuckle. I’ve been researching and educating on former and current labor towns for several years and pieces like his written without any historical context continue to amaze me.

Sen’s piece was right about one thing, “economic realities dictate where these facilities get built.” Corporations build company towns in places without worker protections. They are made in the places urbanites forgot, out of sight, out of the mind of the coastal liberal elites. But they are a poison to the people who must survive in a toxic bubble of capitalistic pretend-live, work, play indeed.

You see, “factory towns” aren’t a new idea, they have been a significant part of Appalachian history for more than a century, but that history never really ended. Appalachians still experience these isolated town structures today, and I can promise, they haven’t uplifted our working class.

By exploring the history of these communities, we can see that towns owned by companies are inherently bad for workers. As history has shown us – and Amazon still does – companies with all-encompassing control over workers don’t just create a cycle of poverty; companies controlling workers is deadly.

So, as national headlines praise this “new” idea that will bolster the middle class (insert eye-roll here), let me tell you about these places that will most certainly not save us.

What is a “Company Town” Anyway?

Most of the well-known reporting on the history of Appalachia focuses on the coal and, in more recent times, natural gas industries that have flourished here.

Due to the work of Appalachian and labor historians, people are also familiar with the union organizing history of West Virginia specifically and its impact on the history of organizing across the country. The Mine Wars of the early 20th century, for example, led to the deaths of coal miners and their families who took up arms to fight against the mine companies imposing crushing work conditions and impoverishment.

Those conditions and cycles of poverty came as a direct result of the company town structure. Company towns are a concept named for the conditions surrounding areas where one industry – usually just one company – was most, if not all, of an area’s economy.

As capitalism entrenched itself as the economic system in the United States, railroad, coal, forestry and banking barons also cemented control over how that system would look. Set in rural areas, away from news reporting or even a nosey neighbor, these companies offered pay, boarding or a mill shack, and subsistence farming in return for 16-hour workdays.

Children as young as six worked in factories, mines and mills. Mary “Mother” Jones started her Childrens’ Strike in Alabama to bring awareness to the backbreaking and soul-crushing labor of the most vulnerable workers.

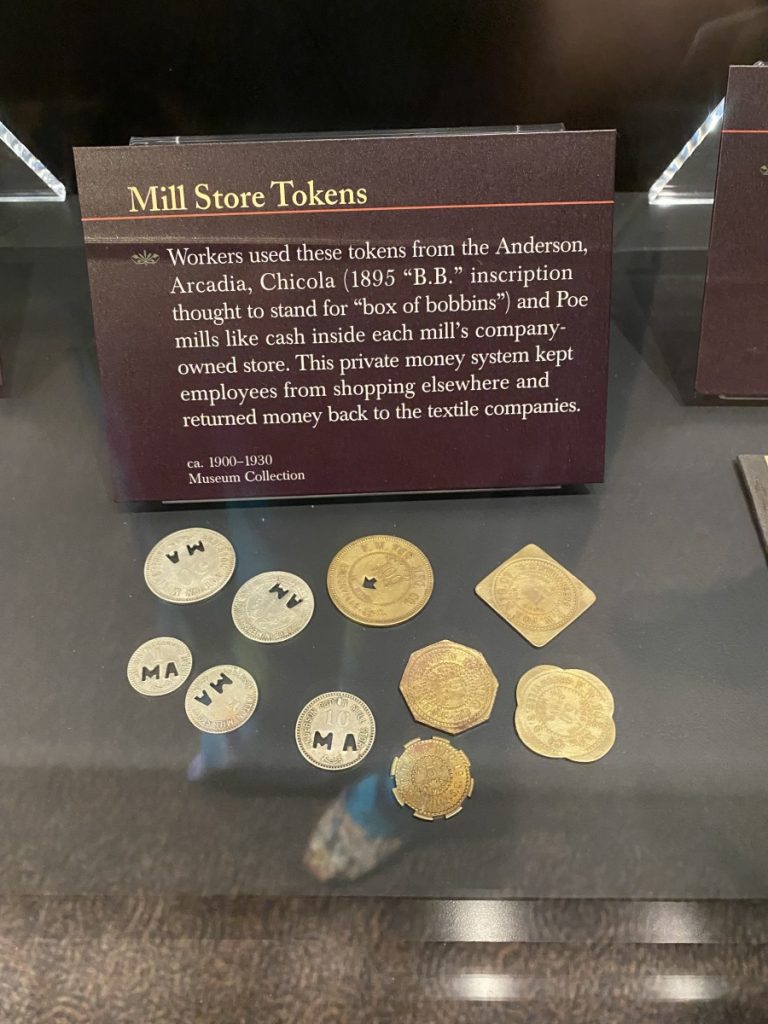

The pay workers were allotted came in the form of scrip – a type of wages usually associated with coal mining but was used by any industry where companies controlled the lives of their workers. Companies paid their workers with this scrip instead of actual salaries or American dollars. The company store took only the specific currency of their company. Workers couldn’t use it anywhere else, and items were marked up to the point of debt, making it impossible for families to leave the company and their towns.

The wretched of the mountains with no options and seen as sub-human, people banded together for better conditions. These efforts usually happened to their detriment: Unions were illegal, and the state and federal governments supported company bosses; bosses often called local police to quell uprisings.

But company towns existed in all parts of the region, beyond the coalfields of central Appalachia. That history, while often overlooked, is the backbone of many a small Appalachian town.

Fort Payne, Alabama, Douglasville, Georgia, and Anderson, South Carolina, are just a couple-few.

A Glimpse into These Appalachian Communities

Driving into Fort Payne is breathtaking. My partner is from the tiny town, and we spend a lot of time comparing small-town upbringing between there and Douglasville, Georgia, where I’m from.

Just outside Birmingham, it is the town in every country song, in every Bruce Springsteen lyric. Its beauty is idyllic and is also a measure of how southern Appalachian economies were built and sustained. It became known as the “Sock Capital of the World” due to the multiple textile mills and factories that supported the town’s economy through the 20th century.

Even now, many work at Cooper Hosiery Mill or one of several factories and distribution centers. Manual labor is the economic engine of the town. The high school, tucked into the mountain, also sits between abandoned mills and still functioning factories that remind students that opportunities include staying to work or leaving for a better set of options.

Mining, of course, has a long history that is the book-end to the Wal-Mart-style company towns of today. While coal mining ravaged the mountains and people of central and northern Appalachia, in Southern Appalachia, it was gold.

The oldest gold rushes in the United States happened in Dahlonega (1838) and Villa Rica (1862), Georgia. The land in the area wasn’t fit for cotton plantations, so textile mills took their place in the southern mountain economy after the depletion of gold in these areas. Many mistakenly believe that southern Appalachia, like the Deep South, was primarily supported by cotton plantations, but mills and factories have been the actual economic foundation of these hills since the post-Antebellum period.

Douglasville, Georgia, is another town in the Smoky Mountains foothills about 35 miles west of Atlanta and 35 miles east of the Alabama state line. My hometown has a forgotten labor history.

Workers in Douglasville were unionized in 1933 and were a part of the General Textile Strike of 1934, just 15 years after the Mine Wars of West Virginia. The strike participation in Douglasville was not successful, but efforts to improve conditions continued into the 1940s. The mill burned in 2012 – a fact I nor any of my friends or acquaintances ever knew until now.

Textile Mills in the Blue Ridge foothills of South Carolina also built mill towns. Anderson, South Carolina, is one of these small towns.

The Pendleton Mill is the oldest cotton textile mill in the state that is still operational. Now owned by La France Industries and in the tiny village of La France in Anderson County, the surrounding area still has its own remote post office, an elementary school, water and sewage co-op, and mill house neighborhood.

Furman University Museum of History curates a company town project on the mill history of Anderson, Pickens and Greenville Counties. Scrip, generally associated with coal villages, can be seen on display, reminding us that all types of companies found ways to control their workers and participate in wage theft.

Employees tied to the company and, therefore, the town earned significantly less than their Northern counterparts. These practices kept the underclass from gaining the power to change conditions.

Like the other mill towns, Anderson has faced significant gentrification by moving away from just one or two industries. This gentrification can erase the rich history of the labor movements in Southern Appalachia, along with the current working and living conditions of residents.

Manny, a friend in Anderson whose family has lived in the area around (“this mill here”) for more than four generations, sees the changes as a positive. I know him to be an amateur expert in the growth and change in Anderson. With a wealth of information and knowledge, he can describe and explain the differences between the architecture of a “mill home” and the concept of a “mill house.” A mill house, he explains, is a one or two-bedroom home, often what many would describe as a shack. However, new and renovated mill houses are becoming chic. These changes can contribute to rising housing and rent costs. Gentrification can dramatically change a neighborhood, but residents don’t always find this a negative outcome.

“I like that they’re building more ‘mill houses’ in this neighborhood. There’s a lot of shooting here and especially across the railroad tracks. There are some girls that bought these houses here (gestures to new and renovated homes across the street); they keep it nice,” Manny says. “The neighborhood is more diverse. As long as they don’t price out the elders that live here, I am for them improving the neighborhood. All [gentrification] ain’t bad.”

Change is inevitable, as they say. Forgetting our history and what happens when we do prevents the difference that truly lifts the working class.

Alana Anton is a sociologist and PhD candidate at Georgia State University where she studies media influence over public perception of Appalachia and on Appalachian identity. She has been a lecturer of sociology for 10 years and makes the best collards you’ll ever eat. She loves her son, Madison, four pitbulls, life partner Shaine and being gay in the mountains.