This article was originally published by Ohio Valley ReSource.

Early on a rainy March morning in Jackson, Kentucky, Yolanda Goff found herself abandoning her trailer on Quicksand Road forever. She didn’t think the floodwater would crest so high, but when she woke that morning, it was in the yard and rising fast. She had a few minutes to salvage everything she could, get her sons into the car and get out. The trailer filled with water behind her. Suddenly, she was homeless.

Hundreds like Goff had their lives turned upside down by the heavy spring floods of 2021, which came in two equally destructive rounds. By late spring, the Biden administration issued a federal disaster declaration, releasing millions of dollars in Federal Emergency Management Agency funds to impacted counties.

A second disaster declaration, for a second round of flooding, opened an additional 22 counties to aid. Local emergency management directors busied themselves with damage assessments and charities, churches and social services agencies dealt with communities’ immediate, basic needs: food, water, short-term shelter. FEMA application deadlines have been extended twice, but five months on, the truth is starting to settle in: for many, the damage is permanent, and the available aid simply may not be enough.

Housing Insecurity Continues

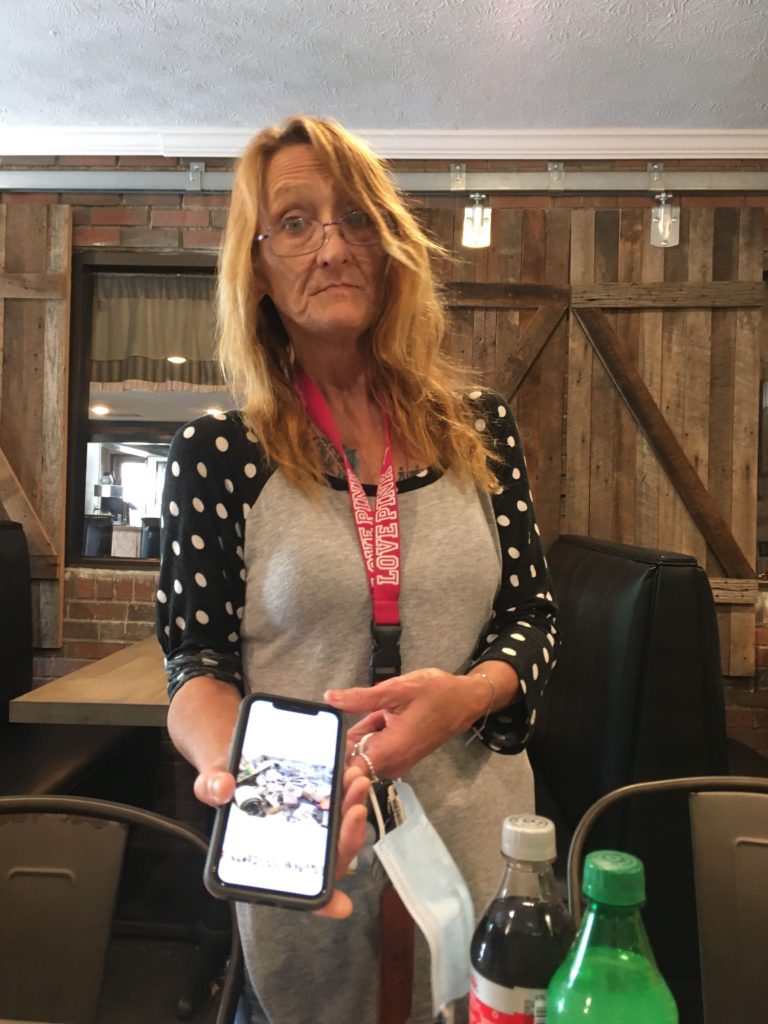

In the Variety Pizza restaurant in Jackson, Kentucky, a number of flood victims sat at the table to eat lunch and tell their stories. Patsy Clair, who runs a nonprofit called Breathitt County Hunger Alliance, had brought them together on a sweltering afternoon in early July. Goff was there, as was 51- year old mother and grandmother Margaret Campbell, who currently is camped out in an RV in front of her old trailer. Campbell’s granddaughter, who is autistic, sat in a booth with her. Campbell says the change has been rough on her family.

“We’re in a 30-foot camper and there’s four of us,” Campbell said. “And it’s hard.”

Campbell accepted assistance from the Red Cross, which included a few weeks at a Perry County motel and a $300 gas voucher. But Campbell says that money was eaten up in a matter of days with the long drives back to Breathitt County back to school.

“A lot of people wanted to help,” she said, “they just didn’t have the funds to help.”

Goff also received a few hundred dollars from the Red Cross, but she needed tens of thousands. When FEMA announced it was accepting applications from her area, it felt like the most viable option. But after filing the initial paperwork, days dragged into weeks, and the whole process made Goff feel humiliated.

“I know what that means,” said Goff, who had only recently finished paying a mortgage on her totaled house. “I’m already in my fifties. I don’t want to pay that off till I die.”

Goff did not take the loan.

As residents struggled with the FEMA application process, some community members stepped up to help. Lesa Marcum is the director of the Owsley County Public Library and has helped disaster survivors file paper, phone and online FEMA applications. Marcum would lend a hand to anyone who needed help with paperwork even if that meant staying after the library closed.

“It takes 7-14 days until they get a response from FEMA. I tell people don’t give up; we’ve come this far, we can wait a little bit longer,” Marcum said.

In 2021, $36,000 was the maximum amount of individual assistance a disaster survivor could receive from FEMA. A survivor may also receive up to $36,000 of “other needs assistance,” according to the agency’s assistant administrator for recovery Keith Turi.

“So you could get up to $36,000 in each category. We also provide rental assistance which is not subject to either of those caps,” Turi said.

However, the agency may still deny disaster survivors rental assistance if damage to their home is deemed “insufficient.”

“There may be circumstances where a survivor applies for assistance and either isn’t eligible because they don’t meet one of those primary eligibility requirements,” Turi said. “Or it could be that the damage to their home is minor enough that their home is not made uninhabitable and therefore, they’re not provided rental assistance.”

Everyone who applies for FEMA assistance doesn’t always get it. A recent NPR investigation found that the poorest renters and homeowners are less likely to receive aid than survivors with higher incomes. Turi said FEMA is working on those problems.

“We recognize that disaster survivors that have been most impacted by historic inequalities have been disproportionately impacted by disasters, and have challenges to accessing disaster assistance,” Turi said. “And we’re working to change that.”

Turi said the agency announced it formed an “equity enterprise steering group” earlier in July to work on those challenges, but could not provide any specific changes or when they might occur.

Because of the lack of reliable access to information and internet service, even applying for that aid can be difficult after a disaster strikes. Even in normal times, many areas of rural Kentucky don’t have reliable internet access, and rely on libraries to file online paperwork. Once flood warnings were issued, some people only had a matter of a few hours or less to leave their homes, making reliable access to information even less likely.

Officials say the lack of aid has long-lasting effects in a place like Owsley County, which has one of the highest rates of poverty in Kentucky at 35.5 percent. If residents can’t get funding from FEMA, Owsley County Judge Executive Cale Turner says it hurts the community.

“The poorer we are, the harder it is to come back from something like this,” Turner said.

Response Worker Burnout

As people talked at Variety Pizza, Patsy Clair, the co-head of Breathitt County Hunger Alliance, quietly took out her notebook and started tallying needs, from furniture to hygiene supplies to clothes and tools. She was giving out gift cards that day, mostly to Lowe’s, disbursing some of the last round of donations her organization had received. She said fundraising for individual assistance has taken a toll on her. She has fielded help requests for other counties, which she is forced to deny, as donations she receives are earmarked for Breathitt County. And as the nation’s attention has turned to other things, money’s gotten sparse. Clair says she’s long known the fallout from the flood would outlast national attention.

“At the beginning of this,” Clair said, “I said, listen, this is not a quick fix.”

While the Hunger Alliance can help with aid, it still falls short of the needs of the community. Clair had hoped FEMA would be able to fill the gap.

The Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky initially fundraised for direct assistance to individuals and families through the Southeast Kentucky Flood Relief Fund. They disbursed roughly 1,300 stipends of $500 each. After spending the money they allocated to individual assistance, Lora Smith, director of the Appalachian Impact Fund, opted to discontinue the program, citing staff exhaustion.

“This was a sprint that turned into a marathon,” Smith said.

The Fund raised an additional $1.2 million through a telethon, which they prioritized for small businesses and farms impacted by the flood. They’ve also shifted focus to supporting affordable housing.

Other groups, such as EKY Mutual Aid, operated throughout the pandemic as a low-barrier-to-entry financial assistance group run mostly on Facebook and mobilized during flooding to offer the kind of immediate, flexible assistance that’s harder for large organizations and government agencies Thousands have joined the Facebook group. But like the others, their capacity is small and their model is based on individual volunteerism. People post their needs in the group, and others choose to donate, or not. EKY Mutual Aid is now beginning to host larger fundraisers and events, but ultimately, said Smith, neither they nor the Foundation could fully fill community needs.

“Really, civil society and the public sector should be doing these things, right?” Smith said. “But they’re not.”

Heavy Rains Impede Recovery

On June 11, a flash flood ripped through parts of Lee County causing more road damage than the floods in early March. Jon Allen, the county’s emergency management director, said flash flooding has caused a lot of problems this year. On July 12, the county was once again dealing with flooding in the area.

“Actually today, last night and into this morning, we had another flash flood in that same area, same road,” Allen said. “And it washed away a lot of our emergency repairs that we had already done. So we’re talking with several different agencies to try to see what we can do to mitigate that problem happening in the future.”

Allen said the damage adds up and can seriously impact the small county’s budget.

“If you look at taking a million dollars worth of road damage, that’s a substantial chunk of our budget for a year,” he said. “That’s the budget that runs our ambulance service for the entire year.”

The night before, waters tossed a culvert, washed out a driveway and cut off access for one resident on Blaines Branch Road. Allen drove uphill surveying the damage. Around almost every bend in the Blaines Branch hollow, the creek rose quickly along parts of the winding, narrow road and took chunks of asphalt and gravel with it.

“See these big sheets of asphalt? Those were just literally picked up in the June event and took and just moved…laid up on the bank,” Allen said.

Allen said flash flooding nearly stranded a lineman making electrical repairs in June.

“Well, the water came in so fast when he was here that he abandoned his truck, took the bucket he was in … and extended the bucket out to the hillside and got out and got on the hillside,” Allen said.

Never-Ending Recovery

As a woman in her fifties already paying off debt pre-flood, Goff doesn’t figure she’ll recover from this. One unplanned disaster, she says, did permanent damage to her finances. She was already in recovery from breast cancer when her home was destroyed and a follow-up surgery had to be postponed. Her mother died three weeks after she lost her home. When Goff went to clean up her mom’s home with her son, a mold-induced asthma attack resulted in a $2,600 medical bill and a $1,400 bill for her son. And she was quick to add that she lost not just her home, but everything inside of it, a lifetime of keepsakes. She is still technically without a home – she shares a room in her neighbor’s house with her two sons.

“The way I feel about FEMA,” Goff said, “is it might work great for some people. But I feel like I lost everything I had, everything I worked for.”

Clair says that she, and the other people at the table, are deeply rooted in eastern Kentucky and dedicated to it. Plus, even for those that would want to leave, moving is expensive, and many aren’t able to afford it. She hopes that out of this, FEMA will see the need for elevated homes, city flood planning and other features of permanent disaster preparedness for the many eastern Kentuckians who will continue to weather storms and bear out floods. No one at the Jackson Variety Pizza that day had any plans to leave.

“Well, you know what,” Clair said, “This is home. Why don’t the people leave the oceanside when they get hurricanes, why are people living in Tornado Alley?”

Clair intends to continue raising money for flood victims for as long as she can. Meanwhile, she encourages people around her not to be ashamed to seek help when they need it.

“Help is out there. You just have to be willing to look,” she said. “Nothing’s easy. You know what I mean?”