This is the first story in Critical Condition, a three part series. Read more here.

In his history of Williamson, West Virginia, Okey P. Keadle – a member of Williamson High School’s inaugural, 1918, graduating class – describes the fire of 1906 that destroyed some 20 downtown buildings. In the long run, Keadle writes, “as is usually the case in such instances, the result was beneficial to the city for it removed all the old buildings on that street and gave room for new ones to be built.”

Keadle’s positive spin on what others might view as calamity is certainly admirable. Though he died two decades before the Great Flood of ’77, in which water rose to the mezzanine level of the Mountaineer Hotel – downtown Williamson’s most recognizable landmark – and well before the beginning of the end of the coal economy through which Mingo County prospered, that brand of glass-half-full optimism undoubtedly served him well: Life in central Appalachia requires a resolute spirit.

Loretta Simon is likewise an optimist. Until it closed its doors April 21, 2020, Simon served as head nurse and chief operating officer of Williamson Memorial Hospital, the staff of which was known as “Your Friends on the Hill.” The 76-bed hospital had been struggling financially; there were potential buyers, but the pandemic derailed that process.

“Things happen for a reason,” Simon says. Lessons have been learned with the closure, perhaps the most critical of which is that a successful hospital in a rural community must leverage the full resources of that community.

Williamson Memorial is now scheduled to reopen, perhaps as early as September. The hospital’s new owner is the Williamson Health and Wellness Center, a federally qualified health center, which over the past few years has been a catalyst in the community for a wide range of public-health initiatives. Simon will return; she’s busy with preparations.

The plan is for Williamson Memorial and Williamson Health to work in concert – in effect, to reopen the hospital while taking every measure to keep people out of it. The health of the community and viability of its hospital will be dependent on a successful symbiosis.

With a global public health pandemic that strained resources on the wane, rural communities throughout central Appalachia – throughout America – are struggling with the question of how to continue to provide hospital care. In some cases, the answer is the merging of hospitals or acquisition by an outside entity – solutions that offer economy of scale (purchasing power, consolidated administration, access to advanced technology) and come at the risk of the loss of attention to the community’s needs and concerns.

The other option, maintaining an independent hospital, is increasingly difficult. Doing so requires rethinking.

Hospitals have been cornerstones of rural communities. The question for those communities today is, “Can we save our hospital, and if not, what are the consequences?”

Williamson Mayor Charlie Hatfield fears the worst. “When you lose your community hospital,” he says, “tumbleweeds.”

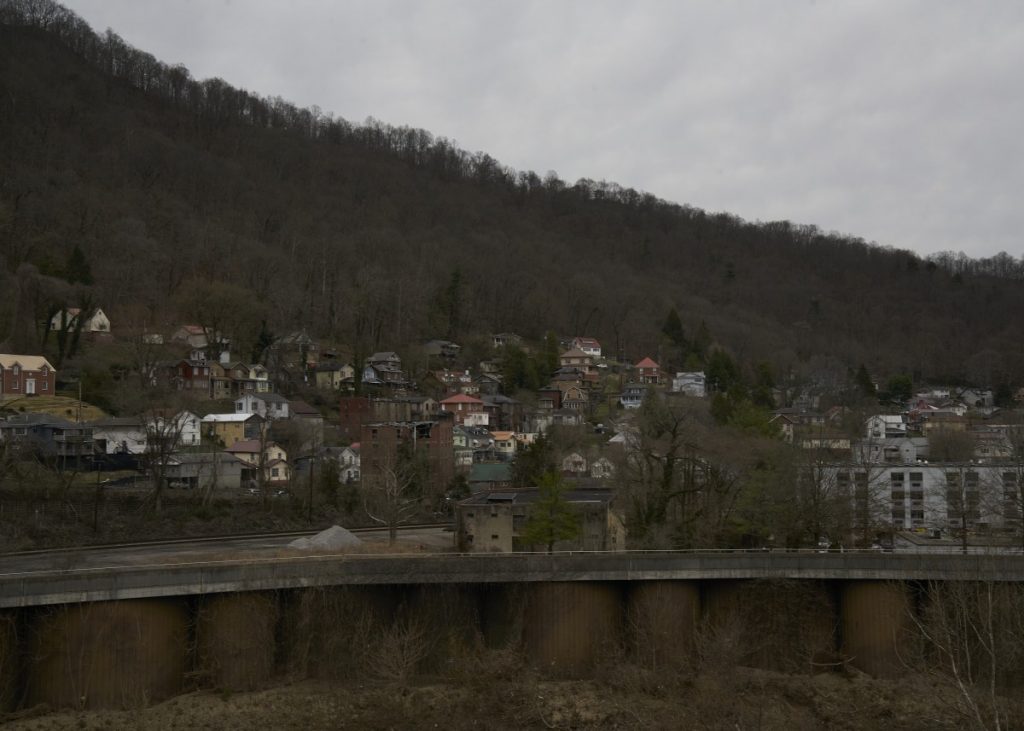

But Williamson isn’t giving up. While an outsider might look upon the weathered edifices that slope up from a once-hyperactive rail yard and see a townscape in terminal decline, ask around.

Ask Michelle Lowe, a former Williamson Memorial nurse who with her husband, Mark, ministers and provides a food pantry for the community through their nondenominational church, Matthew 28:19.

“This isn’t a dying coal town,” Lowe says. This community is designing a healthier future.

The Ripple Effect

The University of North Carolina’s Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research documents 138 rural hospital closures since 2010. A study released in spring of last year found that one in five rural hospitals were at risk of closure due to financial stress. With the precipitous drop in revenue throughout the pandemic, many more are now in jeopardy.

The first consequence of a hospital closure is the loss of the emergency room. Access to specialty care is diminished. Then there’s the economic ripple effect. In many rural communities, the hospital is the biggest employer; tax revenue plummets, other businesses suffer.

News of the closure of Williamson Memorial last year hit the community hard. Generations of families have worked in the hospital; generations of babies have entered the world.

There’s a hospital just a couple miles from downtown Williamson, across the Tug Fork River, but that’s also across the Kentucky state line, which creates issues with insurance, both public and private. The closest in-state hospital is 35 minutes away in Logan, West Virginia. Neither is home to “Your Friends on the Hill.”

Mingo County, of which Williamson is the seat, faces considerable health care challenges. It’s ranked as the second-least healthy county in a state that’s consistently found at or near the bottom in health outcomes.

Williamson’s population (about 2,800 today) has declined apace with its economy – young people leave, in pursuit of opportunities – and its hospital’s patients, like those in most rural hospitals, tended to be older, less healthy and with lower income than the national average. Rural hospitals serve a higher percentage of patients covered by Medicare or Medicaid – which reimburse at lower rates than private insurers – or who have no insurance at all, meaning they provide a lot of care for which they’re never paid.

Jim Kaufman, who heads the West Virginia Hospital Association, calls the challenge rural hospitals face a “double whammy”: a declining population and an inadequate payer mix. This creates a “downward cycle,” Kaufman says, “because you can’t buy new equipment, you can’t upgrade your facility, you can’t fix things.”

The Williamson Health and Wellness Center plays a vital role in this community, offering, on a sliding-fee scale, medical, dental and behavioral care; chronic-disease management; and wellness coaching. No one is turned away.

“We started looking at the community holistically,” says Donovan “Dino” Beckett, the health center’s co-founder, CEO and chief medical officer, born and raised in Williamson.

“Going through med school, I had a sense that I would come back home,” Beckett says. “I just liked that feeling of being on the front line … and it was a way to give back to a community that I felt very fortunate to grow up in.”

The health center is committed to addressing the social determinants of health. It’s structured around the conviction that health care extends to housing, employment, transportation.

Alan Morgan, CEO of the National Rural Health Association, says that when in conversation with rural health professionals, “We spend more time talking about housing, transportation and access to food and dietary issues” than anything else. “If I’m in a meeting and the issues of transportation and housing aren’t brought up, I’m in the wrong meeting.”

Williamson Health and Wellness Center delivers fresh fruit and vegetables throughout Mingo County and oversees a community garden in a public-housing complex. It operates a medically assisted addiction-treatment program (a U.S. House of Representatives investigation found that between 2006 and 2016, almost 21 million prescription painkillers were delivered to two Williamson pharmacies, four blocks apart) and recently received funding for a workforce-development initiative to help get those in the program back to work.

Amy Hannah, the health center’s community resource network director, recalls attending her first national health care conference and hearing that “your zip code can determine the longevity of your life” – the consequences of living in an area with no public transportation, for example, no grocery store, no sidewalks – “and I’m thinking, ‘There’s no way.’”

But as she began to understand the impact of social determinants, she set about to translate what she’d learned to her community to overcome those obstacles.

“It’s been a challenge,” Hannah allows, “but we’re getting there.” The health center convenes small focus groups. “We pull people with lived experience to the table” to “freely speak about what matters.”

“We need people who have been there and done that and can say, ‘No; that doesn’t work; this is what does.’”

Carolyn Dillard, 40, a single mother of two young boys, is one such person, a “community champion,” Hannah says. Dillard experienced postpartum depression and counsels women on confronting it, on the importance of focusing on their own mental health. “Eventually, it’s going to catch up to you,” she tells them. “And if you’re not in a good place mentally, then your kids are going to suffer from it too.”

Fierce Loyalty

Several generations back, when coal was king, Williamson’s 2nd Avenue was lined with businesses run by immigrants from all over the world – Italians, Syrians, a vibrant Jewish community. There was an opera house. In the 1930s, the population was close to 10,000.

In 1918, as Okey P. Keadle was plotting his future, Williamson Memorial Hospital opened its doors. Two years later, a nursing school was built next door.

In 1927, the hospital was destroyed by fire, and a year later a three-and-a-half-story gabled-roof hospital was built atop College Hill, a half mile as the crow flies from the Mountaineer Hotel, the heart of downtown Williamson. For 60 years, she gazed reassuringly on the town.

In 1988, a new Williamson Memorial was built just down the hill, and over the decades, the staff there forged a fierce loyalty, among themselves and with their patients. It seems most everyone in Williamson has a story to tell of one or the other of those hospitals.

Tammy Chapman, Amy Hannah’s sister, began working as a lab technician at the hospital in 1998. “Our hospital had a working-family atmosphere,” she says. “I didn’t realize how close we were until we went through it all.” By “all,” she means the hospital’s closure.

“It was devastating,” Kathy Carey, a longtime nurse, says. “You kind of knew it was going to happen, and they did tell us a couple of weeks before it closed that it was definitely going to happen. So, it was just a sense of dread. Every day you go to work, you thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, pretty soon this is gonna be the end.”

“The last day together was really, really hard,” she says. “We came back at midnight when they closed the doors. We all gathered around and had a farewell party.”

Carey now works at Tug Valley ARH Regional Medical Center, the hospital across the river, where she sees many of her former Williamson Memorial patients. “They’re all the time saying, ‘Oh, we hope the hospital reopens’ and, ‘There’s no place like Memorial.’”

‘Look What I’ve Done!’

In 2012, the Williamson Health and Wellness Center launched a CDC-funded community health worker-based program addressing diabetes that significantly lowered participants’ blood sugar levels. The program hired local people to visit patients at home, monitoring their blood sugar, making sure they knew how to take their medications, talking about nutrition – in general, determining what’s needed to allow this person to live a healthier life. They then leveraged the program’s success to confront congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Community health workers are foundational to the center’s success.

Melissa Kennedy, 54, had long suffered from rheumatoid arthritis, type 2 diabetes and hypertension. “I made preparations to die,” she says. “I mean, I was that sick. … My grandbaby was 6 years old, and I kept thinking, ‘I won’t see him turn 10.’”

Kennedy was put in touch with Jerome Cline, a Williamson Health and Wellness Center community health worker. Due to COVID-19 precautions, their first visits were via telehealth. Cline’s first question in their initial session, she recalls, was, “‘What did you have for breakfast?’ And I said, ‘I’m a cereal eater.’ ‘What kind did you have?’ I said, ‘Cocoa Pebbles.’ He said, ‘Melissa, you don’t know anything about sugar?’ And I said, ‘Not one thing.’”

She told Cline that her father’s lower leg had been amputated due to diabetes, “but I don’t know anything about what he can eat and what he can’t.”

“He said, ‘Take your computer and turn it around. I want to see what medicines you have. I want to see what kind of food you have. Open your refrigerator; open your cabinets.’”

Cline arranged for Kennedy to take nutrition classes with Melissa Justice, the center’s community health worker project director. She remembers Justice calling her in the mornings, saying, “Go in there and check your sugar. I need to know what it is.”

“There is a huge realization of the cost savings of diabetes management,” the National Rural Health Association’s Alan Morgan says. “The outcomes are just dramatic.” It’s a matter of saying, “In this community, here are easy ways that you can take control of your own health.”

“Every major insurance company now, they’re all launching their own chronic-care management programs,” Morgan says. “Those guys are in it for the money, and they wouldn’t be doing it if it didn’t work.”

Kennedy had relied on a wheelchair or a walker; she now uses neither. Incrementally, through counseling and encouragement, her health has improved. The “care and guidance” of Cline and Justice “has changed my life,” she says.

Now, when she goes into the health center for an appointment, “I sort of feel like I could jump up on top of the picnic table and say, ‘Look at me! Look what I’ve done!’”

Taking Control

“It used to be we were going to provide every single service in our community, and I think people realize we can’t do that,” Jim Kaufman of the West Virginia Hospital Association says. The most essential question for rural hospital administrators today, he contends, is, “How do we get creative?”

The financial damage inflicted on rural hospitals by the pandemic is expected to accelerate mergers and acquisitions.

But, Morgan says, “I think there is a role for a small independent hospital that has a strategic alliance with a larger health system,” a hospital that’s focused on preventive health and chronic-care management and on “empowering the community to take control of their own health, as opposed to just treating them only when they show up in the emergency room.”

Burgess Dalton worked in underground coal mines for some 25 years; he suffers from stage 4 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Community health worker Jerome Cline has regularly scheduled visits with him too and shows up in between as needed with antibiotics or a steroid shot. Prior to their visits, Dalton was in the emergency room every month or two; it’s been 14 months since he was last there.

That, of course, is the objective – keeping people out of the hospital. Meanwhile, Loretta Simon prepares for the reopening of Williamson Memorial. She’s also been helping administer COVID-19 vaccines at a drive-through site. “To be able to see the faces, to connect our purpose with that patient – that’s been my driving force.”

It was a rough winter in Williamson. Then one spring morning, Simon arrived for work, and it was as if, overnight, every bud had blossomed. “It gives hope,” she says. “Where flowers bloom, there’s hope.”

The hospital will reopen in phases starting as soon as this fall. The first phase will include the emergency room, diagnostic services, an extended-hour Williamson Health and Wellness Center clinic and a few additional services. Initially, some 80 people will be employed.

Simon assures her neighbors that preparations are progressing. “So many people are watching and waiting.”

This is the first story in Critical Condition, a three part series. Read more here.

This story was funded by the National Geographic Society. It also had financial support from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.