It’s easy to find examples of how not to cover extremist violence and groups in American news coverage. On the national level, everyone from the New York Times to Fox News consistently platform white supremacists and other dangerous extremist ideologies, handing over their pages or airwaves (inadvertently or not) to spread these messages. However, it’s important to acknowledge that local and regional reporters have, at times, also failed to safely and effectively document extremism in the past year.

Earlier this year, we published a list of tips for local journalists who find themselves experiencing an increase of this activity in their community on how to appropriately cover the topic. We know there are a myriad of challenges facing local newsrooms, not the least of which is a strain on resources. For local and regional reporters, not every article on extremist activity is a feature length piece that comes after weeks of reporting and investigation. We are often juggling multiple stories at once, and in the past year, breaking news and politics reporters found themselves standing across from armed militia groups with little to no preparation or context for covering the event. And all of this came with an extremely tight, mostly likely daily deadline.

As we’ve pointed out, extremist activists are media savvy and will seize any opportunity to inject their rhetoric and ideology into a story – a frazzled reporter desperate for quotes presents an attractive chance to do so. But it is time for us all to do better.

In this article, we’re going to look at two examples of local coverage of extremist activity in a community on a local level. We need to look at these failures not to condemn or disparage the reporters who produced this work, but to learn from our mistakes. Extremist groups in America are evolving, and so must our understanding of the role we play in spreading hateful and violent rhetoric.

Where We Can Do Better

In September 2020, Louisville, Kentucky, hosted the 146th running of the Kentucky Derby. Outside the Churchill Downs track, thousands of Black Lives Matter activists gathered peacefully, hoping to draw attention to the murder of Breonna Taylor and other Black Americans at the hands of law enforcement.

Various far right extremist groups – namely heavily armed militias – also made a point to congregate in Louisville that day. Rather than approach the large BLM rally near the track, many of them made their way downtown – where there was a reduced law enforcement presence – and attempted to attack people in Jefferson Square. That’s where BLM activists often congregated near a large mural for Taylor during a summer of civil protest in the city.

Reporters from across Kentucky and the surrounding area gathered to cover the demonstrations that day, uncertain if violence would be the result of the meeting of the two opposing groups. Militias, BLM and other activists, and law enforcement were spread out all over town. Journalists were forced to make snap decisions about which large group to follow and where to position themselves to best cover the day as it unfolded. While most national coverage focused on the protest at Churchill Downs, some followed the large militia groups that made their way into the city.

Below, we’ve taken the body of an article produced by a local media outlet covering the day’s events and noted opportunities for improvement. The article here is presented in its entirety, but split into sections for discussion, without the headline or byline of the publishing outlet and journalist.

FALSE EQUIVALENCY

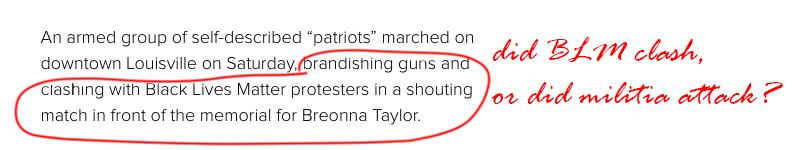

Below is the first sentence of the story covering the events in Louisville that day and the first instance of potential improvement in our reporting.

Using words like “clash” and “battle” implies an equal and intentional convergence of two opposing forces. It’s a convenient narrative device, often deployed to simplify complex situations. However, in this case (and many cases involving extremist political activity), such a simplification is not just reductive, it’s harmful. It plays directly into misinformation campaigns and extremist rhetoric used by various far right groups to justify violence against those they disagree with politically.

The Black Lives Matter movement is not “against” conservative Americans or far right groups. According to organizers and participants, the movement is against systemic white supremacy and the murder of Black and Brown people by law enforcement officers. Militias, Proud Boys and other far right extremist groups have, on the other hand, consistently attacked and declared themselves to be directly opposed to the BLM movement. When these two groups interact, there is often heated verbal exchanges and occasionally violence. When violence does occur, it is Black Lives Matter activists who are most often left with injuries or worse.

This isn’t nuance or semantics but vital context for street violence that cities and towns across America are experiencing. The way we frame these moments is important. Saying a militia “clashed” with BLM activists implies that the militia was met with an equal and opposite level of violence and violent intent, when in reality, this roving band of armed paramilitary civilians attacked a static, peaceful demonstration.

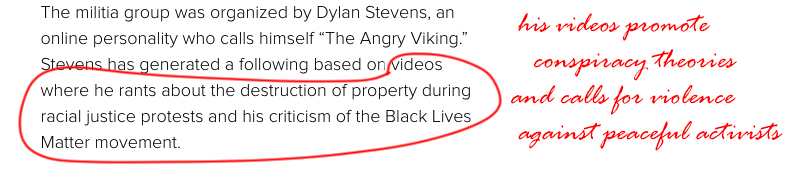

PLATFORMING

As written, this article functionally serves as uncritical propaganda for a conspiracy theory peddling far right extremist who spent most of 2020 harassing Black Lives Matter activists, advocating for violence online, setting up local chapters of these groups across the country and recruiting members. Below is the next section of reporting.

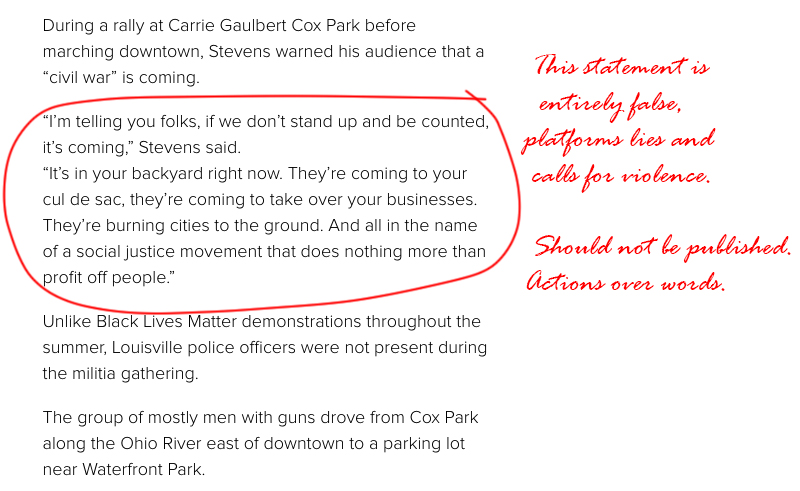

Giving the leader of this extremist group an entire paragraph to espouse objectively untrue statements, as is also seen below, without any critique or contextualization implicitly endorses the statements being made. Our readers trust us to give them the best contextualization of a situation. In this instance, it would have been better to paraphrase the quoted section, rather than publish the direct quote we see here:

The newsworthy aspect is not the inflammatory rhetoric this man espouses, but the fact that he and his group are actively looking to harass and engage in violence in public spaces based on objectively untrue claims. Especially after the leader of this group was allowed to uncritically claim that the Black Lives Matter movement is “burning cities to the ground” and “they’re coming for your cul de sac,” the earlier depiction of the altercation between the groups could easily be read as confirming the leaders claims.

“When we are dealing with impacted communities, and we’re dealing with systemic issues, it’s not only not acceptable, it’s not ethical journalism to give white supremacists the same space to voice their opinion that you’re giving a Black mother whose child was shot by the police,” said Chelsea Fuller, deputy director of communications from Team Blackbird – an organization that supports grassroots movements – and the former leader of the Youth Criminalization program for the Advancement Project, explained as she looked over this article. “Nor is it balanced, because the communities are not on equal footing in terms of access.”

ERASURE

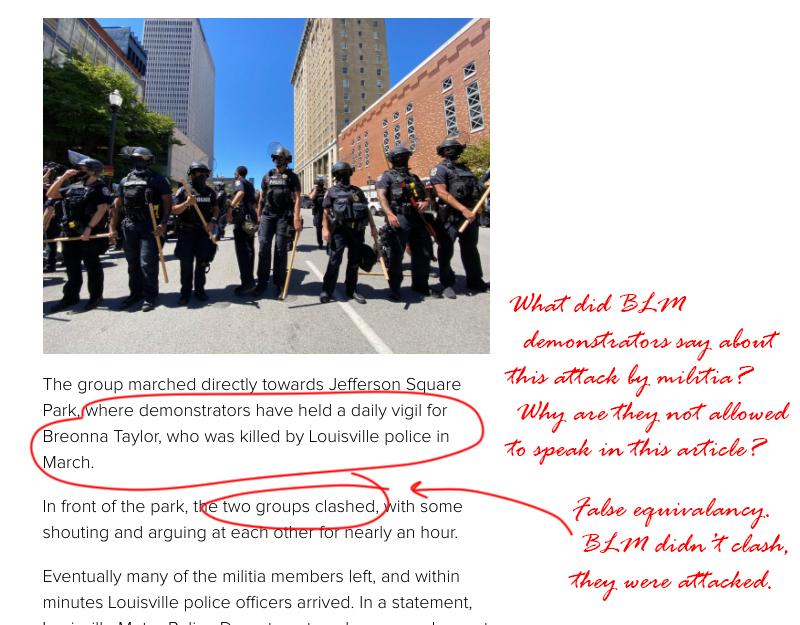

The most glaring absence in this article is the voice and perspective of those who were directly targeted by this far right group: the Black Lives Matter activists in Jefferson Square.

The broad absence of the perspectives and voices of targeted community members in the coverage of far right violent groups plays directly into the hands of extremists, making them appear less threatening or serious to audiences who don’t experience right wing terrorism every day.

This is, of course, hardly a recent or modern phenomenon. In 2021, it’s commonly known the KKK was and is a racist hate group who murdered, lynched and terrorized thousands of African Americans and other groups from the post-Civil War Reconstruction period onward. However, after the wildly popular racist silent film, “Birth of a Nation,” was screened in President Wilson’s White House in 1915 – a film glorifying lynching and the Klan – and, in reaction to the economic advancement of Black Americans during the Great Migration to the industrial North, and the racial tensions amplified by economic downturn in the wake of WWI, the KKK hired a PR firm that had recent expertise in patriotic propaganda for the war effort. They refashioned the Klan as a Christian (although virulently anti-Catholic), patriotic, wholesome, family-centered fraternal organization sponsored by local businesses. That narrative continues to be forwarded by the media and challenged by the Black press to this day.

But on the street today, when far right and left wing activists converge, the scenes are often chaotic and can become violent quickly. It can be difficult to speak with activists while they’re being attacked – in the moment they are far more concerned with de-escalation and their physical safety than your interview needs. However, this is a vitally important element of covering these moments.

If you are on the ground and struggling to get the perspective of those on the receiving end of far right wing harassment and violence, it may require stepping away from where the groups are directly engaging and finding someone nearby who will speak with you.

In this article, the absence of any direct quotes or perspective from the BLM activists effectively hunted down by a group of armed and hostile vigilantes is a glaring flaw, and one that editors should have identified and flagged as a serious issue to rectify before publishing.

MORE FALSE EQUIVALENCY AND A SOLUTION

This article does a good job of describing how the militia prepared to attack the BLM protestors, handing out cans of insecticides to spray peaceful protestors – an excellent embodiment of reporting on actions, not words. Unfortunately, this article fails to apply the same effective reporting technique to the scene that unfolded when the militia reached Jefferson Square, as seen in the section above. “The two groups clashed, with some shouting and arguing with each other for over an hour” is, simply put, an inadequate description that creates yet another false equivalency.

“That word clash insinuates that there was wrong on both sides, and that’s a narrative that exists now – that there are two groups of people that showed up to fight or to enter into some kind of disagreement, entanglement, whatever,” Fuller explained.

Being extremely mindful about the language we deploy as reporters and how it primes our audiences to receive information is vital to responsibly handling these moments. As Fuller points out, a single word can have larger implications.

“There’s nothing overtly criminalizing or derogatory here about the Black Lives Matter movement, or the folks that have shown up to to stand and supportive that,” she said, “but that word ‘clash’ does have a particular connotation that connects to the mainstream narrative, especially when we had a president for a while that was really doubling down on the idea that everybody involved in these moments was wrong. And that is just unequivocally false.”

Rather than summarize extremely complex and tense interactions as a “clash,” it can be helpful to use a “three act” approach to summarizing these moments:

Act one identifies which group approached the other with violent intent and how the other side responded and focuses on what they do over what they say, act two uses a specific moment or scene that you as a reporter think best embodies the overall activity and act three describes what ultimately de-escalated the situation. A hypothetical rewrite of the “clash” using this framework could look like this:

When the militia group reached Jefferson Park, they began shouting at Black Lives Matter activists while holding cans of insecticide in their hands. The Black Lives Matter activists congregated across from them on the sidewalk with signs, intending to prevent the militia from moving into the square. (Insert here a sentence that describes one of the shouting matches, paraphrasing what each side was shouting at the other). After an hour, the tense moment de-escalated when the militia group left the area.

This type of depiction is an important tool for preventing reporting from playing into the hands of extremists and becoming a recruitment tool. By highlighting which actions increased the threat of violence breaking out (the militia approaching the BLM activists with insecticides and weapons) and which actions decreased the threat of violence (the militia leaving the area and the two groups being physically separated from one another), the reporting also gestures towards de-escalation solutions and can inform public safety measures in the future.

HOLDING POLICE ACCOUNTABLE

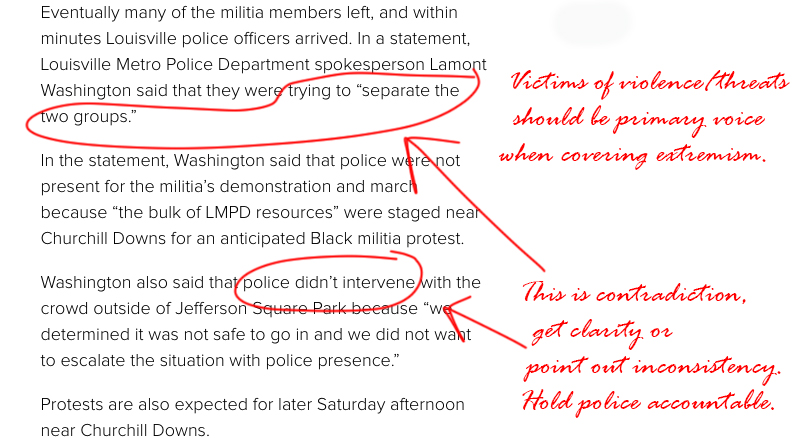

At the end of the article, a spokesperson for the Louisville Police Department gives two completely contradictory statements, as seen below.

At first, the spokesperson says that law enforcement tried to separate the far right group that attacked the BLM marchers. In the next paragraph, the spokesperson is quoted as saying that law enforcement didn’t try to separate the groups – and in fact earlier it’s noted that law enforcement did not arrive at Jefferson Square until after the militia group left the area. When law enforcement says something so visibly contradictory, it is crucial that this discrepancy is, at the very least, explicitly acknowledged.

Getting quotes and a response from law enforcement in the midst of protests or other extremist activity can be very challenging and is often simply impossible. Law enforcement spokespeople will sometimes provide periodic statements to the public in regards to these situations, and it’s up to reporters to contextualize their comments.

The depiction of the law enforcement response as written in this example is confusing and contradictory. If the bulk of law enforcement personnel and equipment was devoted to monitoring an armed militia group that congregated at Churchill Downs, why did another armed militia group walking through downtown Louisville intentionally provoking hostile interactions with peaceful demonstrators not warrant the same level of attention? What about the situation that unfolded at Jefferson Square made police consider it too dangerous to enter? These are reasonable questions for our community members to ask of us and, therefore, we should be seeking the answers during our reporting.

It’s possible that what the spokesperson was trying to express in this instance was that while there was law enforcement in the area of the square, there were not enough officers on hand for them to contain the situation if it escalated to violence. If this was indeed the case, this would mean that law enforcement left so few personnel on hand to deal with a militia group that Louisville Police was unable or unwilling to intervene.

Again, the fact that the two groups seemingly separated from one another on their own volition without law enforcement intervention is extremely important. It suggests that organic and self-imposed de-escalation occured between these groups – a very important element to document and highlight when possible. Since law enforcement didn’t resolve the situation, who did? Were there militia members and BLM activists who led the de-escalation? Who was responsible for the situation resolving peacefully? What do those who actively contributed to the groups not resorting to violence have to say about the situation, its resolution and the lack of law enforcement intervention?

What We Can Model

While many local news outlets are understandably scrambling to learn how to cover this issue while also keeping up with their day-to-day reporting responsibilities, others are investing in this type of coverage and the time it takes to contextually get the story right, like Bert Johnson at Nevada’s Cap Radio. Johnson spent the past year working with colleagues on a series of stories documenting far right extremist activity in their area and have developed some effective strategies for covering this beat that any reporter can put in their toolbox. Fuller has some suggestions as well.

BEFORE YOU REPORT

The work to get these stories right begins long before you step foot in the field.

“First and foremost, if you are covering something that is in any way, shape, or form connected to racialized violence, or any social or systemic issue, really think about who the players are,” Fuller suggests, “not in terms of the players in the mainstream narrative, but thinking about story at its basic sense. Who are the folks in conflict? Who is driving the core issue here? And when you think about that, thinking about journalism as a vehicle to deliver important information to people, who are the people that actually need to know this story? Who are the people that probably don’t want it out?”

Fuller also encourages reporters to think about extremism in the context of other beats. “If you’re covering policing, or if you’re covering right wing extremism and all you’re really focusing on are these really narrow kind of siloed lanes, you’re actually missing a lot of storytelling opportunities, so read about how the climate movement is talking about white supremacy and extremism. Look at how it’s being talked about in terms of business and economics and housing.”

For Johnson, it’s also important to understand the extremist groups or ideologies he encounters in the field well in advance. “The far right speaks its own language, they develop their own language, in their own subculture. And then there are subcultures within that, of course, because the far right is a very broad term,” Johnson said.

It’s important to be well versed in the language and subcultures of far right groups because it will enable you as a reporter to recognize when an interviewee is simply regurgitating talking points they found through social media or extremist propaganda. If it’s necessary to even quote far right groups at all, it will help ensure that you’re quoting people, not the propaganda they hope to platform through your outlet.

Another important aspect of covering extremism is sources, or determining in advance the individual or institutional experts you can quote or link out to. For Johnson, covering QAnon in Nevada meant ensuring he linked his articles to sources that gave important context.

“In terms of resources, the first thing I’ve tried to do and keep consistent with [my] QAnon coverage is linking to sources that will explain the anti-Semitic history behind the ideology. Groups like the Anti-Defamation League do a good job of this.”

“I’ve put a focus on talking to experts on cults and deprogramming, because [QAnon] is a cult,” Johnson said of his work to make the explanation of these types of groups accessible to his audience. “People know what a cult is, they know that it’s bad and know that it controls people’s minds. So if you put it in that frame right away, they have that tool set available to them. And then you can make the historical connection.”

Johnson also acknowledged that some organizations and institutions are perceived as too partisan, regardless of how reputable or factual their information is, and it’s important to recognize which sources will be best received by your audience.

When covering extremist activity, reporters in rural areas especially are likely to encounter firearms in the hands of activists. Some reporters have little to no experience with firearms. Encountering them in the hands of activists can be frightening, and it’s natural to want to avoid agitating these individuals with confrontational questions. However, the presence of firearms at a protest, rally, or other politically charged event should be explicitly noted in your reporting.

“Anytime you have a weapon at a political event, that is intimidation – specifically guns. Any time you have a visible firearm at a political event, that is political intimidation, and that’s not a partisan stance,” explained Johnson.

While many who openly carry firearms to public activism will likely suggest they are simply carrying a weapon for protection or to prevent oppositional political groups from attacking them, the reality is that the effect – if not the intention – is intimidation and fear. This should be central in reporting on extremist activity in public spaces, especially when politically oppositional groups interact and firearms are present.

A CASE STUDY

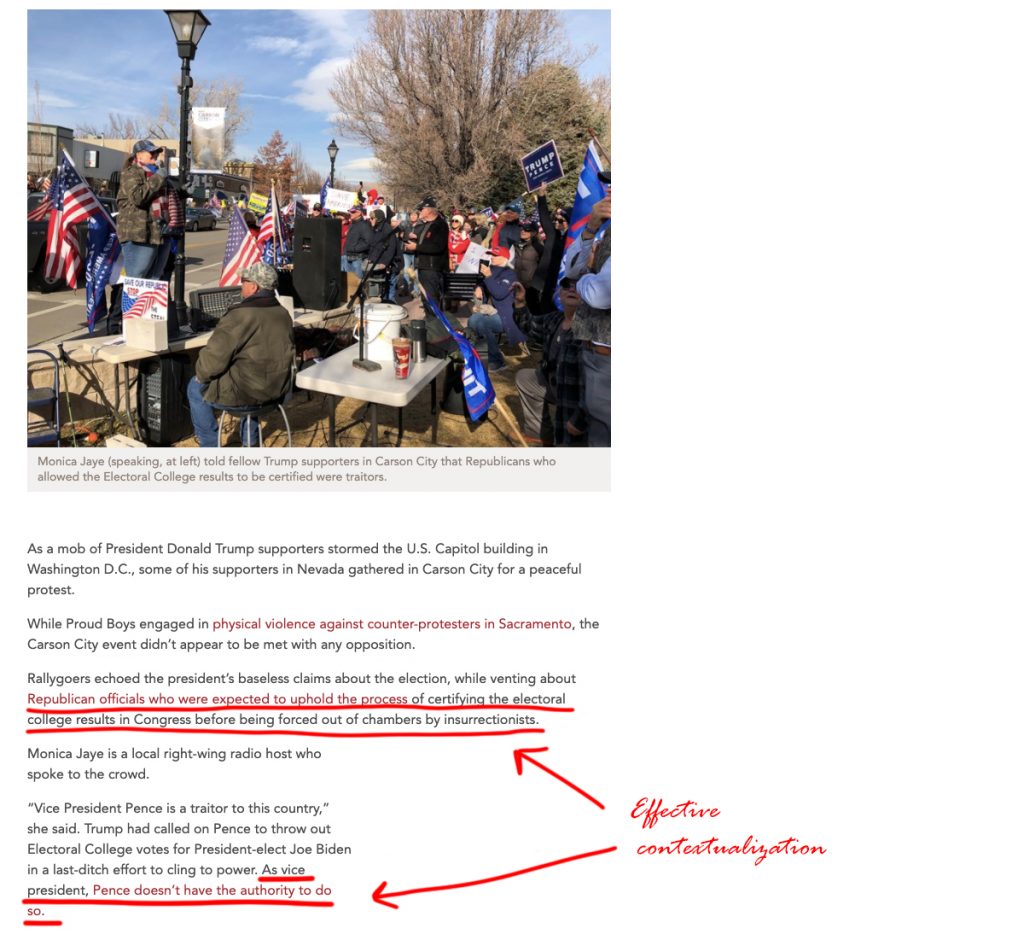

On January 6, pro-Trump “Stop the Steal” rallies were held across the country. While most media focused on the attack on the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., local reporters were covering smaller rallies and protests in their areas, including Johnson who spent the day covering a pro-Trump protest in Carson City, Nevada.

The protest in Carson City wasn’t met by any counter-demonstrators, meaning that Johnson spoke exclusively with pro-Trump activists. Avoiding platforming of potentially extremist rhetoric in this type of situation can be difficult, and at times electing to not cover at all is the preferred news judgment; however in this case, contextualized coverage helped to shine a light on the growing role of youth in far right movements. Rather than publish quotes without any pushback or accompanying critique, Johnson made sure to contextualize quotes from the demonstrators, as we’ll explore in his reporting.

When a right-wing radio host declared the former Vice President to be a “traitor” for refusing to throw out Electoral College votes, the quote was immediately followed by an explanation that the former Vice President was not legally able to do this, as seen in the above section of his report.

When Johnson spoke with one of the organizers of the rally, as seen below, he paraphrased the organizer’s belief that the 2020 presidential election was “stolen” and immediately pointed out that the organizer had no evidence for his claim, as well as the fact that both local and national officials had firmly rejected this allegation.

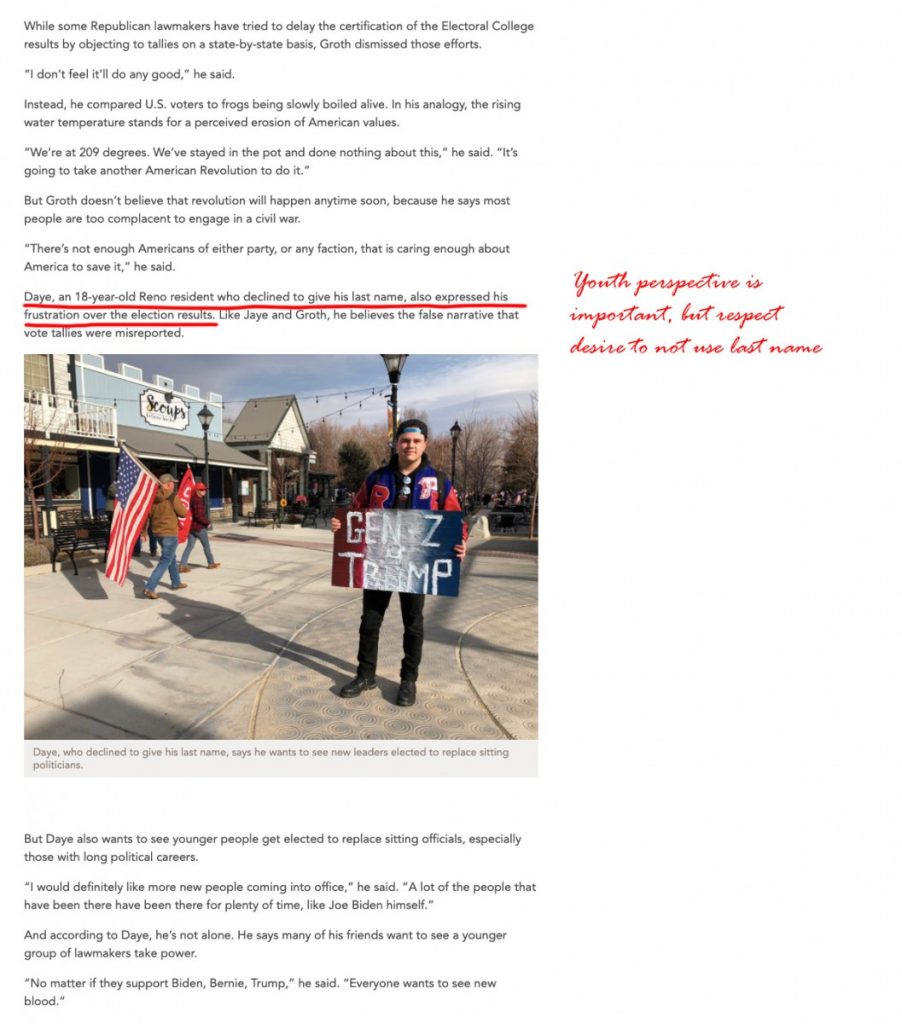

Towards the end of the article, Johnson spoke with a young participant. Interviewing minors or young adults comes with important ethical and professional considerations, but it’s relevant to include their perspective when covering this type of activism. For one, political organizations across the spectrum are invested in appealing to younger Americans, as they represent the largest growing demographic of voters in the coming years. Young people are also targeted by these groups to normalize fringe or extremist beliefs, especially through online spaces and viral content.

“I wanted that young perspective, what is it that’s driving young people to become enthralled by this false narrative? And then also, like, what’s his perspective on the system more generally?” Johnson explained of his choice to include the youth perspective. “He’s legitimately there as an attendee. So obviously, I have to contextualize his beliefs and I did that right at the top. I really want to hear his perspective on the generational power imbalances.”

Johnson verified that the young activist was in fact 18 years old, but also respected his wishes to not have his last name used in the article. While young activists are important to report on, they also deserve special consideration and care as interview subjects. A teenager participating in a political rally or espousing extremist inspired rhetoric is different from an adult doing the same. While all of us are accountable for our actions, younger people are more likely responding to influences rather than instigating them, and the potential consequences for identifying a child or young adult in the context of covering extremist activity should not be taken lightly.

When a teenager speaks to a reporter, they may not fully understand the consequences of being quoted in a news article or the implications of their statements, especially the permanence of these statements are part of the public record, so reporters should carefully consider whether quoting younger participants is vital. If interviewing a younger person involved in extremist activity, ensure that you’re focusing on what’s unique from their experience rather than allowing them to serve as a spokesperson for what adults have told them. Proceed with caution, and do no harm.

That said, teenagers are just as capable of dangerous or violent activity. Kyle Rittenhouse was only 17 years old when he shot three people in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and this should not be taken as encouragement to avoid or dismiss their agency.

Chris Jones is a Report for America corps member covering domestic extremism for 100 Days in Appalachia. Click here to help support his investigative reporting through the Ground Truth Project.