This article was originally published by Ohio Valley ReSource.

Dr. Kirk Tucker, chief clinical officer of Adena Health Systems in Chillicothe, Ohio, said a week before Thanksgiving that the health system’s three hospitals in southern Ohio were bombarded with coronavirus patients. But it isn’t just the patients testing positive. The virus has also sickened 65 of his fellow caregivers.

Recently, Tucker said, a doctor there in his 60s tested positive for COVID-19 and died the same day of a sudden cardiac event.

“This physician, to my knowledge, did not feel bad,” Tucker said. “As a matter of fact, I saw him the day that this happened.” Tucker said one of the many dangerous things about COVID-19 is that the virus is prothrombotic, meaning it can cause blood clots.

“When you draw blood on some of these people, it no sooner than gets into the blood container, than it starts to turn to jello.”

A hospital nurse, eight months pregnant, was transferred to another hospital after testing positive for coronavirus and experiencing “failing respiratory health,” Tucker said. A few days later, Tucker said the nurse is “hanging in there.”

“I share these stories because people need to understand how horrible this is,” Tucker said.

A day before Thanksgiving, 4,449 COVID-19 patients were hospitalized in Ohio — a number that had increased by more than 1,400 over the previous 11 days. The state has fluctuated between 68 percent and 78 percent of its total hospital capacity during November.

“And the weird part about this wave is usually we watch what happens in the major urban centers like Columbus to our north, and we will sort of follow their surges,” Tucker said. “This time, it was the reverse. We had the first surge.”

Chillicothe is a city of just over 21,000 but, like many parts of the Ohio Valley, it is experiencing a rural surge of coronavirus that has gone far beyond major cities and isolated outbreaks in jails and nursing homes. That is straining the smaller hospitals and health centers that serve those rural communities and small towns. As Dr. Tucker’s experience shows, it’s not just a question of available beds — hospitals could face staff shortages as more fall ill or face quarantine amid the uncontrolled spread of the virus.

“This COVID-19 is absolutely crushing, crushing the rural clinical staff in these hospitals,” Alan Morgan, CEO for the National Rural Health Association, said. “I can’t stress that enough, there’s limited ability to make errors, basically, and once you lose 10 to 15 of your nursing staff, you lose a few of your primary care physicians, you’re in crisis mode.”

Hospital Capacity

Rural hospitals already faced capacity and staffing issues before the pandemic. Morgan said he isn’t sure how rural hospitals will fare over the next couple of months, but he thinks more rural hospitals will close.

“Simply stated, rural America is a place where those most in need of health care services, oftentimes have the fewest options,” Morgan said. “And it’s just the makeup of rural America, rural America is older, sicker, poorer, it has a much higher percentage of elderly, many with multiple chronic health issues.”

Chillicothe’s Adena Health System’s three hospitals serve nine rural counties. As the hospital system COVID-19 unit filled up, medical staff reached out to larger cities to arrange transfers.

“We have already reached now, several days, where we’ve called Columbus, Cincinnati, Dayton and none of those hospitals can take COVID patients — they’re full,” Tucker said.

Although statewide hospitals haven’t reached capacity, John Palmer, Director of the Ohio Hospital Association reported that some of the state’s eight regions have few ICU beds available.

Elsewhere in the region, hospitals are beginning to take measures to absorb the expected growth in demand. The University of Kentucky’s Chandler Hospital in Lexington announced it will close five of its operating rooms beginning Monday, Nov. 30. “UK HealthCare’s COVID-positive patient numbers continue to grow and during the last week, the total COVID census has increased above 70 patients daily,” according to a UK HealthCare press release.

The hospital has 32 ORs and could close more if total COVID patients increase to 90.

Pikeville Medical Center CEO Donovan Blackburn echoes the same concerns for the eastern Kentucky communities served by the hospital. Twenty-two people have died from COVID-19 at the hospital since October. The weekend before Thanksgiving the hospital’s ICU was nearly at capacity.

“But what’s going to happen is that we’re going to have to start declining our own patients, within our own region, our own service area,” Blackburn said. “And those patients are going to end up either in a different part of the state or possibly in another state as well.”

As the holiday approached, coronavirus patients occupied more than 1,650 hospital beds around Kentucky, 390 of them in intensive care units. In an email last week, Susan Dunlap with the Kentucky Cabinet of Health and Family Services said 1,713 ICU beds have staff, but the state’s total 2,066 ICU beds can be used whether staffed or not.

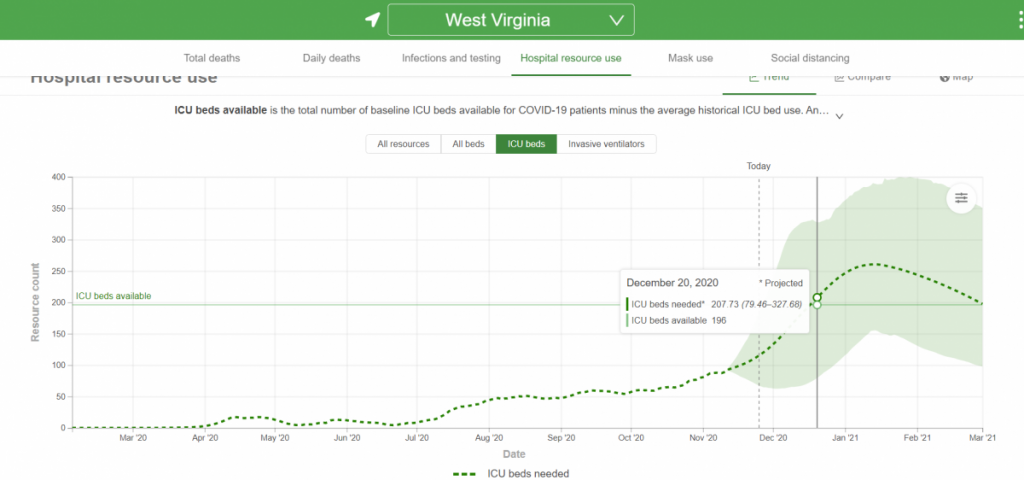

In West Virginia, 501 COVID-19 patients were hospitalized with 144 in ICU beds on Wednesday. According to the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, West Virginia has more than 3,000 hospital beds, and is not in danger of nearing capacity. However, the state has 196 ICU beds available, and the IHME model predicts that the demand for ICU beds in the state could surpass the state’s supply a week before Christmas. The IHME data show Kentucky and Ohio could also run short of ICU beds in December if current hospitalization trends continue.

Sick Staff

As more health care workers get sick, the supply and demand for medical workers is becoming more immediate than hospital capacity issues. Retaining health care workers in rural settings has always been a challenge, but the situation has worsened.

At Pikeville Medical Center, Blackburn said, medical staff can work anywhere from 12 to 16 hour days. In addition to long work days, patients in the hospital’s ICU unit are “very sick,” he said. So far, some employees have tested positive for the virus and have been hospitalized, but none of the cases have been life threatening.

To address staffing gaps in Chillicothe’s Adena hospitals, Tucker said nurse practitioners with their own practice have been asked to work in its hospitals and several have done so.

“One of them is working seven days a week, seven days a week, she hasn’t had a day off now in I think three or four weeks,” Tucker said. “Some of them work a full day shift in their office, and then leave their office, change into scrubs and then work on the floor at night.”

Nurses and doctors take critical steps to care for sick patients, and in an effort to streamline care an emergency effort to reduce paperwork has been implemented.

“We have dialed back on what is required of nursing staff to document in the computer to streamline their jobs and get them at the bedside more but that only lends itself to some improvement,” Tucker said. “You can’t really safely take a nurse and ask him or her to care for 10 or 15 critically ill people, and these people that are on the COVID unit are not well.”

Costly Replacements

Across the board, the U.S. needs medical workers, and oftentimes, hospitals rely on staffing agencies to find nurses.

“Earlier in this pandemic, we could simply redeploy clinicians into these rural communities from their larger health systems or from other states, we don’t have that ability anymore,” the Rural Health Association’s Morgan said.

What nurses are available through agencies cost hospitals much more money.

“They’re having to pay anywhere from four to 500 percent more than what they would normally be paying for an agency nurse,” Nancy Galvangi, president of the Kentucky Hospital Association, said. “And that is because Kentucky is in competition with other states, other states that can pay a lot more.”

Across the Ohio Valley, hospitals anticipated $2.7 billion in losses associated with the pandemic. Galvagni said the additional costs of agency supplied nurses will increase Kentucky hospital losses.

“And I think we’ve testified to the fact that these COVID patients are sick — if you look at a COVID wing, they require more staff than the average patient, they require a lot more PPE, they require a lot more therapy,” Galvagni said.

Such cost increases hit especially hard at rural health facilities like Pikeville Medical Center. A few months ago, CEO Blackburn said, an ICU nurse might cost $68 to $78 per hour at the center, but today that cost could be anywhere from $165 and $200 per hour. On top of paying more, it could take nurses up to a month to arrive at a new hospital, Blackburn said.

Although Kentucky hospitals received some CARES Act funding, Galvagni says more is needed.

“We would love to see additional federal relief funds,” she said. “So I think that is something that we’re working closely with [Kentucky] Senator McConnell on making sure that Kentucky gets a share of those relief funds, because, you know, we do have these losses that are out there.”

The Ohio Valley ReSource gets support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and partner stations.