Immigration and Customs Enforcement agreements with a single county can affect an entire region, immigration advocates say. In East Tennessee, Knox and Greene counties maintain such agreements, while larger metropolitan areas have backed away from them.

In 2018, an ICE raid in a Bean Station, Tennessee, slaughterhouse made national headlines. Ninety-seven workers were arrested. The second-largest ICE raid in history, it was a harbinger of the East Tennessee immigration crackdown just around the corner.

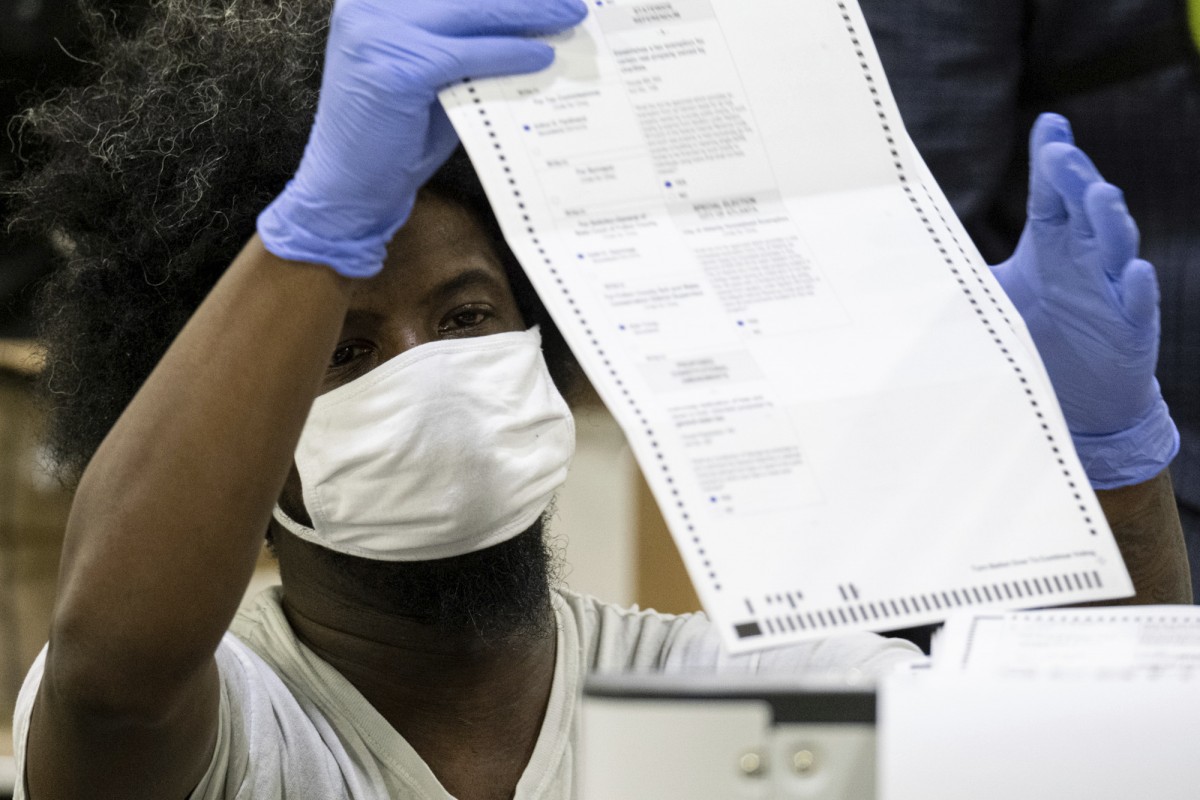

Knox County Sheriff J. J. Jones had just signed two, linked contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), each intended to remove immigrants from East Tennessee faster than before. One, 287 (g), deputized corrections officers as ICE agents; the other, an intergovernmental service agreement (IGSA), or detention bed contract, reimburses the Knox County jail $83 per person, per night for every immigration detainee.

According to immigrants’ advocacy organization Allies of Knoxville’s Immigrant Neighbors (AKIN), these events ruptured holes in the families and communities of undocumented people throughout rural East Tennessee.

Two years later, in a September 25, 2020, virtual press conference, AKIN members discussed their recent investigative report on the Knox County 287 (g) program. While the Knox News Sentinel reported in 2018 that the intention of the double contract was to save money on detention costs and lessen the time that ICE detainees spend in jail, AKIN members said that it imprisons immigrants in a Kafkaesque maze of court dates, holding facilities and legal fees.

When deputized Knox County officers call for an ICE hold, immigrants are held beyond their judgment of innocence or guilt. ICE picks them up within 72 hours and transports them out of state to an ICE detention facility, without informing their families as to which one.

The sheriff’s department says that the agreement lowers crime rates. Tom Spangler, the Knox County sheriff, renewed the contract again in May. “If you do not commit a crime, you won’t go to jail,” declared Spangler in a video.

According to the report, 84.6 percent of ICE holds in Knox County were charged with nonviolent misdemeanors, mostly traffic incidents, and 21 percent of these were booked on accusations of driving without a license. It’s a catch-22 since licenses are illegal for undocumented people to obtain.

The report centers on Knox County, but it has large implications for rural undocumented people. “In Morristown, since this ICE raid happened, there’s just been this atmosphere of fear,” said Hammad Sheikh, a Knox County immigration lawyer and board member of rural immigrants’ organization Hola Lakeway.

Rural Implications

Sheikh described regular calls from surrounding counties from undocumented victims of crimes who are terrified of calling 911 for fear the police will take them instead of the perpetrator. That mistrust, he said, will take a long time to heal even if 287 (g) is revoked.

Sheikh was quick to add that even though 287 (g) is only active in Knox County and Greene County, many will drive through either of these regularly. Greene County is a hub for undocumented workers because of its agricultural industry. Knox County is home to the closest quality medical treatment, among other services, for many East Tennesseeans. Many also hold jobs in the tourist hub of Sevier County, which is only reachable through Greene or Knox for those who reside in Hamblen County, where Latinx constitute 11.5 percent of the population.

The consequences add up even for those who are released on bond, which requires up to $10,000 and a local sponsor to reduce flight risk. Released people are mandated to report to Knoxville’s ICE office, a small piece of federal property accessible only by personal vehicle. Lineup occurs outside the building, rain or shine, from 8:30 a.m. every Wednesday morning.

Many travel from surrounding counties, as this is the only ICE office in East Tennessee. AKIN members reported that random detainments have become a mainstay of this process — sowing terror into people who comply with the law, except perhaps for the fact that they drove to Knoxville. That’s a short distance, though, compared to immigration court, which before COVID-19 was in Memphis — a 14-hour roundtrip for a 10-minute appointment.

The consequences reach deep into communities and families. Dani Urquieta, a student activist, grew up in a Mexican-American household in Morristown, where most of the workers arrested in the 2018 Bean Station raid lived. Urquieta said the constant threat of deportation induces unsafe working conditions for rural undocumented people who labor on large farms and packed factories.

Because the employers willing to pay undocumented workers are few, their power is immense, and labor law violations are routine. “Your situation is super particular,” said Urquieta. “You can’t think that you’re in any position to talk about the unfair working conditions that exist. If you get out, where else are you gonna go?”

No Evident Benefits for the County

According to Pew Trusts, Tennessee is in line with national trends: Urban counties are removing themselves from agreements with ICE, and suburban and rural counties are entering them.

The program’s logistical problems, described partially in this internal report by the DHS, coupled with community uproar, have induced many Democratic cities to opt-out. Davidson County, the urban county that encompasses most of Nashville, withdrew back in 2012. Meanwhile, East Tennessee’s Greene County, whose agriculture economy depends on immigrant labor, entered into it in 2019.

The Greene County sheriff’s department didn’t respond to requests for comment.

This article was originally published by The Daily Yonder.