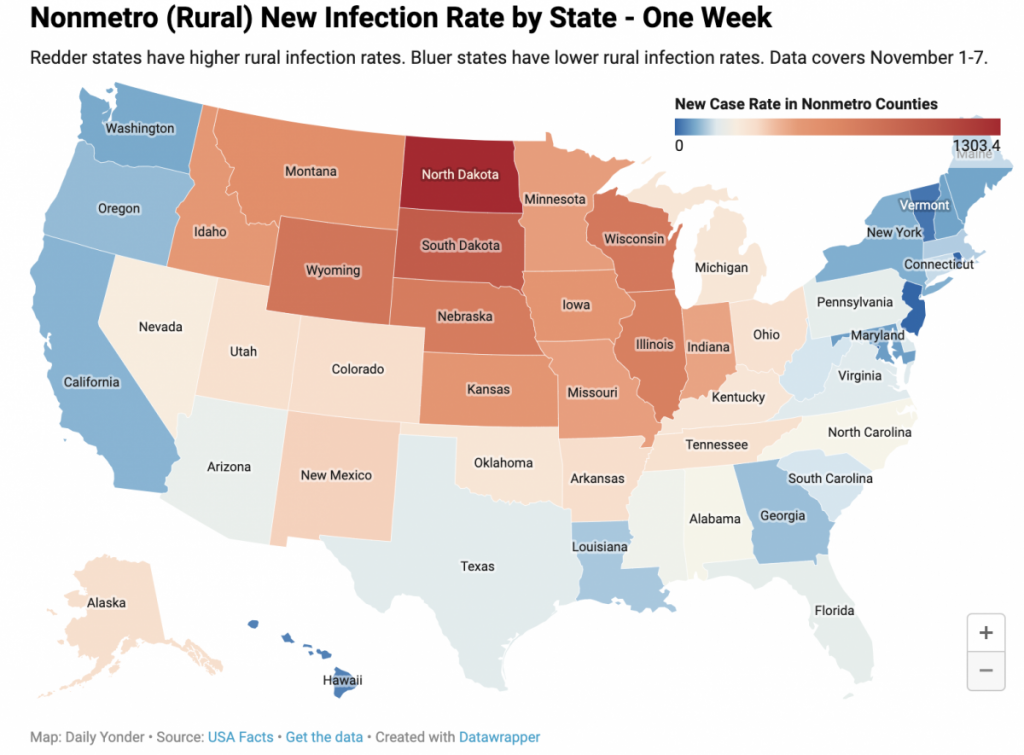

Most rural hospitals did not have large numbers of COVID-19 patients this spring and summer. The current record-breaking surge in rural areas will likely be different.

Most rural hospitals didn’t get inundated with COVID-19 patients during the spring and summer surges of the pandemic. But the accelerating spread of the virus in rural regions has a Midwestern hospital administrator wondering how they will rise to the challenge.

In February, Lexington Regional Health Center in Lexington, Nebraska, braced for an onslaught of COVID-19 positive cases. The only hospital for the town of just over 10,000, Lexington Regional watched and waited for cases to come through their doors.

Meeting almost daily, the hospital staff prepared for the worst – switching some rooms to isolation units, constantly assessing their supply of personal protective equipment and adapting to the latest guidance from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention.

But cases didn’t start to come until mid-April, when the hospital started to see as many as four COVID-19 patients a day. That surge lasted a few weeks as it cycled through a meat packing plant nearby.

Now, the hospital faces a much grimmer outlook, said Lexington Regional administrator Leslie Marsh. Staffing shortages, bed shortages at the state level and funding issues will make the impact of the coronavirus much worse for rural hospitals, she said.

“The state is way worse off in terms of staffed-bed capacity, … and that impacts all of us — especially rural,” Marsh said. “The state’s ability to care for patients that require hospitalization, intensive care and ventilator care is very concerning and untenable.”

Multiple factors are affecting hospital capacity, Marsh said. For example, “critical staffing shortages have compounded the problem and there is no easily identified ‘quick’ fix.”

Dawson County, where Lexington Regional is located, has more than doubled the number of deaths due to the coronavirus since spring.

“To date, Dawson County has had 17 potential deaths with two ‘questionable,’” Marsh said in an email interview with the Daily Yonder. Questionable cases patients who test positive for COVID-19 but are admitted for other issues.

The local public health district has had 48 total potential deaths, with eight of those being questionable.

“The state is way worse off in terms of staffed-bed capacity, … and that impacts all of us — especially rural.”

Leslie Marsh, administrator of Lexington Regional Health Center in Lexington, Nebraska

On Friday, November 6, the county reported 24 new cases. Other counties near Dawson also reported increased cases – 85 in Buffalo County, 11 in Kearney, 10 in Phelps.

But treating them, she said, was exacerbated by national nursing shortages.

According to a study cited by the Nursing Times, as many as 36 percent of the nurses responding to a survey by the Royal College of Nursing were considering quitting. A survey by HolliBlu, an online nurses’ support group, found that 62 percent of their members were considering quitting.

For rural hospitals that have difficulty getting help in the first place, Marsh said, nurse shortages during a pandemic are a costly problem.

Marsh said a recent report shows a quarter of nurses nationally have left hospital positions or nursing in general since the pandemic’s start.

“This is important to Nebraska because we are not only experiencing this phenomenon, [but] demand for nurses is way higher than in ‘normal’ times and it is becoming difficult if not impossible to secure nurses from any place and in any way.”

Traveling nurses, those nurses that will come into an area temporarily to work, have filled the gap, but those nurses add to costs. Marsh said traveling nurses in Nebraska urban areas can earn up to $150 an hour, which can attract rural nurses who don’t earn that kind of pay.

“Rural already operates without much bench depth and is being disproportionately impacted by nurses leaving the profession/hospital role and also leaving rural positions to travel,” Marsh said.

Donald Lloyd, president and CEO of St. Claire Regional Hospital in Morehead, Kentucky, said that his hospital has had to bring in traveling nurses to handle the influx of cases they are seeing as well.

“We have experienced some staff who has just decided that, you know, life is too short, and this isn’t what I want to do the rest of my life,” he said. “And some, because of the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, they’ve had to leave – they might have small children, and there’s not another person to help with the children or they’ve had to hang up their nursing shingles to become a home-school teacher right now.”

Lexington Regional Health Center in Lexington, Nebraska and St. Claire Regional Hospital in Morehead, Kentucky

Also, he said, outside nurses were brought it to give existing staff a break. What administrators across the country thought would last a few months has now stretched into eight months, with no end in sight.

“Currently, we are experiencing our largest volume of Covid-positive patients that we have seen since the pandemic began,” Lloyd said.

After an initial outbreak in April, the virus seemed to plateau in June, rise again after July 4, but then level off for a while, Lloyd said. But the eight-county Eastern Kentucky region St. Claire serves has seen cases on the rise again.

“Since October we’ve just seen an increase in not only active cases, but the acuity of those cases,” he said. “And again, those patients that are typically being hospitalized right now are patients with underlying relevant risk factors or a significant chronic health conditions that makes them more vulnerable.”

Most patients, he said, are cared for at home. But of the eight patients in the hospital now, however, four are in intensive care and two are on ventilators.

Rural hospitals remain financially vulnerable but things have improved since the early period of the pandemic. St. Claire regional furloughed 300 employees earlier this year – most of them in academic or administrative positions – to help the hospital stay afloat.

To mitigate the spread of the coronavirus, Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear shut down elective procedures at hospitals, eliminating major income streams for hospitals.

On May 25, however, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Recovery and Economic Stimulus (CARES) Act, which provided funding to hospitals, and extra funding to rural hospitals.

That money is gone now, he said.

“We’re so grateful for it because it got us through the very, very worst elements of (the COVID shutdowns),” he said. “But we’ve used the entire allegation for the additional expenses, like bringing in reinforcements, and getting some of the supply-chain issues fixed on a personal protective equipment.”

“Since October we’ve just seen an increase in not only active cases, but the acuity of those cases.”

Donald Lloyd, president and CEO of St. Claire Regional Hospital in Morehead, Kentucky

The hospital is still fully funding all of the community testing for the area.

But so far, there’s no word of any relief coming out of Washington, D.C., he said. Instead, the hospital has adjusted operations to meet obligations.

For Lexington Regional in Nebraska, the strings attached to the money mean they can’t use it to the way it would be most helpful.

“The use of provider relief funds, according to the most recent [Health and Human Services] FAQs, are questionable,” Marsh said. “We had planned to build an ER that met present day demands, add HVAC systems to OB rooms and to the rest of our smaller COVID wing. We are waiting for final guidance, which is supposed to arrive mid to late-November. Currently, even the most generous reporting guidelines to date require us to report and use funds by June 30. So, capital infrastructure like the desperately needed ER addition will be nearly impossible to realize.”

Her fear, she said, is that those funds would be taken back if they’re not used in a very specific way.

“The current FAQs have us wondering if we will be able to use these funds at all,” she said. “While rural is nimble, adapting and innovating quickly and effectively, (CARES Act funding) is a short-term fix…But it is inefficient and does not allow us to be as functional as we could be if the provider relief funds were able to be fully deployed in a way that allowed us to more effectively meet what is becoming a long-term situation.”

This article was originally published by The Daily Yonder.