The nation’s pandemic hotspots have shifted to rural communities, overwhelming small hospitals that are running out of beds or lack the intensive care units for more than one or two seriously ill patients.

And in much of the Midwest and Great Plains, hospital workers are catching the virus at home and in their communities, seriously reducing already slim benches of doctors, nurses and other professionals needed to keep rural hospitals running.

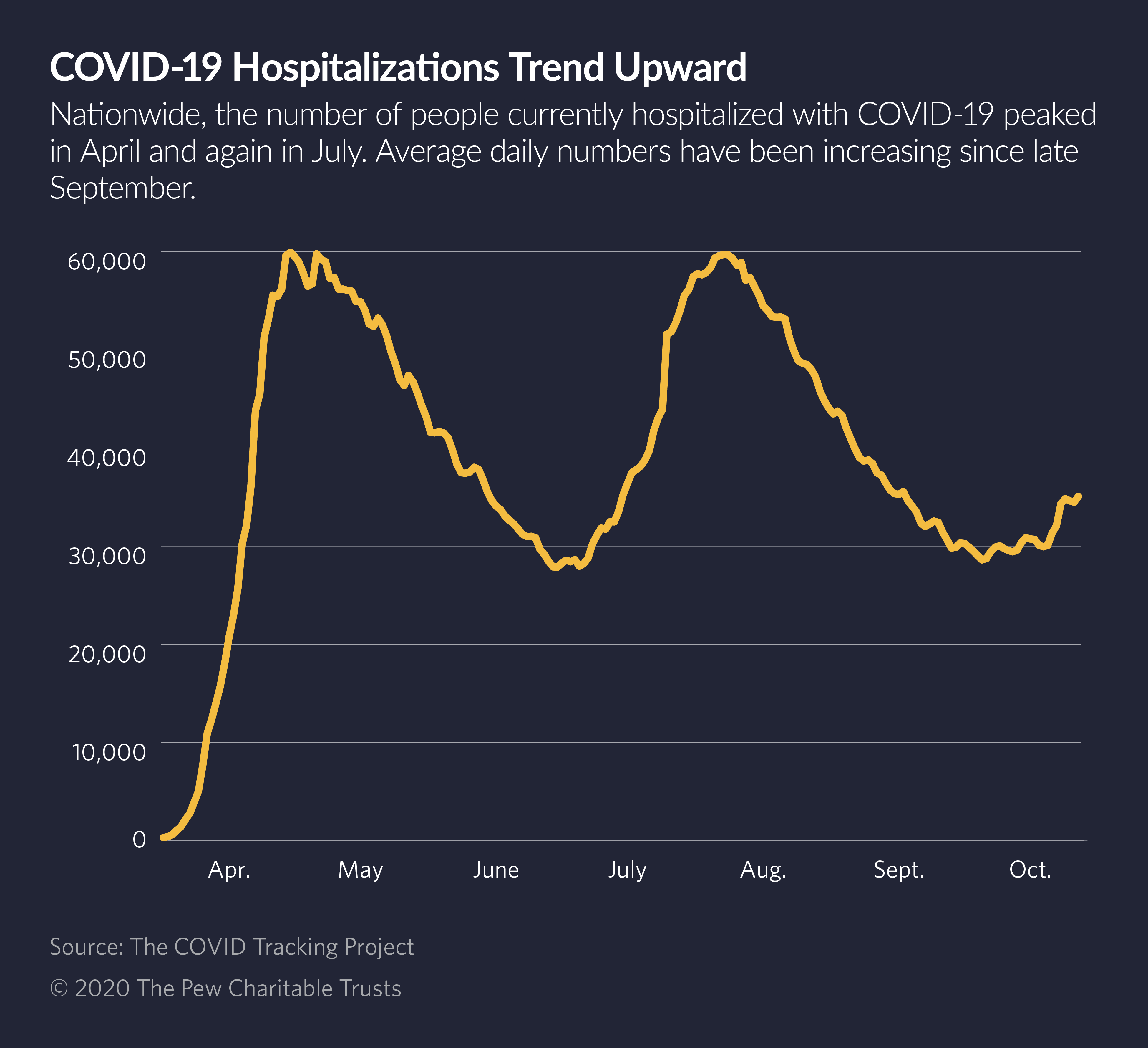

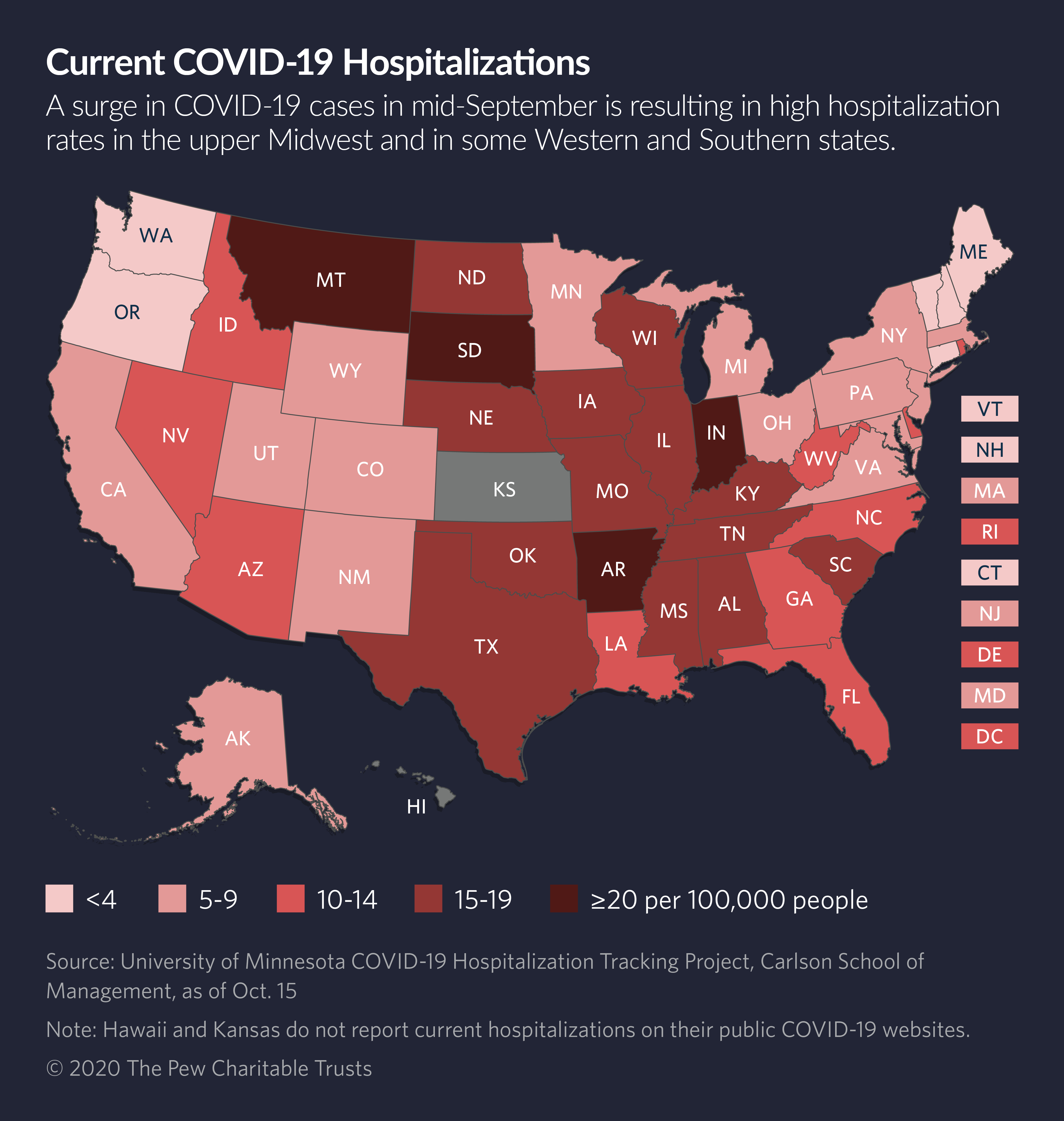

Nationwide, positive coronavirus cases started rising in mid-September as children and college students returned to school, more businesses reopened and more people started resuming daily activities outside of their homes. Wisconsin and other less populous states became the new hotspots.

This week, per capita rates of COVID-19 were highest in North Dakota, followed by South Dakota, Montana, Wisconsin, Nebraska, Idaho, Utah, Wyoming, Iowa, Arkansas and Illinois. Hospitalization rates also were rising in those states and others.

Health care experts expect that a seasonal spike in flu and pneumonia, combined with a steady rise in COVID-19 cases, will swamp many health care systems, particularly in rural areas.

Wisconsin recently opened a 530-bed field hospital on state fairgrounds in Milwaukee that was set up in the early days of the pandemic but sat unused until now. Last week, 50 beds were readied for patients, and the staff was working on transfers with hospitals that were hitting their capacity limits. The number of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the state tripled in the last 30 days.

In Oklahoma City and the surrounding area, no ICU beds were available last week, according to the University of Oklahoma. The lack of beds required medical professionals in those already understaffed hospitals to spend hours on the phone arranging patient transfers to other Oklahoma hospitals.

Fewer than 20 ICU beds were available in the entire state of North Dakota, according to state data. That meant patients had to be transferred hundreds of miles, in some cases to South Dakota and Montana.

Wisconsin averaged more than 3,000 new COVID-19 cases every day last week, and nearly a thousand COVID-19 patients were in the state’s hospitals every day. That’s compared with a daily average of fewer than 300 COVID-19 hospitalizations in the state in early September.

Hospital workers there are feeling the emotional distress.

“They’re angry,” said Tim Size, executive director of the Rural Wisconsin Health Cooperative.

“We keep asking people to wear masks and social distance, and they don’t change. Health care workers don’t understand why so many people are acting as if the virus doesn’t exist. They just don’t understand them,” Size said.

“They’re acting like we’re not all in the same community,” he said. “But the virus thinks we are.”

Since the beginning of the pandemic, Wisconsin’s deeply divided government has been unable to work together to promote evidence-based public health measures. And even now, as Wisconsin leads the nation in new cases and hospitalizations, the Republican-led legislature is refusing to work with Democratic Gov. Tony Evers on a statewide plan, Size said.

About half the population wears masks and the rest don’t. “They say in Wisconsin you can guess how a person is going to vote by whether he’s wearing a mask,” Size said.

The current COVID-19 wave in Wisconsin was predictable, given the lack of mask wearing and social distancing, he said. “But it’s really sad, because we’re going to have a rough fall and winter, and it was preventable.”

Nationwide, health care experts expect the current nationwide COVID-19 wave to last until at least January, surpassing the two previous waves in case counts, hospitalizations and deaths.

According to the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, nearly 129,000 U.S. hospital beds will be needed to care for COVID-19 patients by January 2021, when the institute expects the current wave to peak.

That compares with an estimated 69,000 beds used by COVID-19 patients in April when outbreaks in New York City, New Orleans and other cities peaked, and 62,000 hospitalizations in July when the second virus outbreak peaked.

In a September press briefing, Dr. Christopher Murray, director of the health metrics institute, said U.S. hospitals should start preparing for a surge that he predicted would build slowly in October and pick up in November and December as temperatures dip and people are forced indoors. He said he expected the rise in cases and deaths in the winter would be large enough to trigger some governors to reimpose quarantine restrictions.

Better Prepared

Hospitals everywhere are better prepared for COVID-19 patients than they were in March and April, according to Nancy Foster, vice president of quality and patient safety for the American Hospital Association.

Better treatments have been developed, including powerful steroids to protect the lungs.

“In addition, we’ve gotten more comfortable at watching the data and being able to react in each community to make sure we have room to accommodate both COVID and flu patients without necessarily shutting down surgeries,” Foster said.

She said U.S. hospitals have strengthened their existing cooperative relationships, allowing hospitals that are nearing capacity to quickly transfer patients to other, less-busy hospitals.

But in rural regions, where more than half of all hospitals have no intensive care units, there aren’t many transfer options when a patient suddenly becomes critically ill.

“They’re on the phone in the middle of the night calling one hospital after another to find one that has an available ICU bed,” said Brock Slabach, senior vice president for member services at the National Rural Health Association.

In this current surge, he said, many rural hospitals have had to transport patients a hundred miles or more to a hospital with an ICU, potentially tying up a community’s only ambulance.

Of the first 100,000 COVID-19 deaths in the United States, about one-fifth occurred outside of urban areas. Of the second 100,000 deaths, nearly half were non-urban residents, according to an analysis by NPR.

Right now, Slabach said, the nation is seeing even higher mortality numbers in rural areas, as the proportion of deaths in mid-size cities and rural communities rises.

Rural populations tend to be older, sicker and poorer than urban populations and they have less access to medical, dental and mental health care. Those disparities likely will mean that a higher percentage of rural residents infected with the coronavirus during this surge will end up in hospitals. And no matter how prepared they may be, there will be shortages of staff and personal protective equipment, Slabach said.

Rural hospitals don’t have access to the same supply chains that larger hospitals have and staffing shortages can quickly become critical when one health care worker in a department of two falls ill.

In addition, cash is in short supply. Forty-eight percent of rural hospitals have negative operating margins, and the median number of days of cash on hand for all rural hospitals is less than 33. Since 2010, 132 rural hospitals have shuttered, 15 of them just this year.

Testing shortages also are plaguing rural hospitals. Unlike larger hospitals, they can’t afford their own testing labs, so they have to send tests out to commercial labs, which are experiencing delays.

That means that when health care workers are exposed to the virus or have symptoms, they must quarantine for at least four days until they get back their test results, further reducing rural hospitals’ available staff.

Many larger hospitals have expanded their available space for COVID-19 patients by converting parts of their buildings to ICUs. That hasn’t happened in rural hospitals. In fact, rural hospital capacity is shrinking, Slabach said. More than 75 percent of rural hospital revenue comes from outpatient services.

“Unfortunately, COVID patients can’t be treated that way. They need to be in a hospital bed,” he said.

“We’ve always wondered what would happen in a pandemic, particularly a respiratory pandemic that requires beds and how we would respond. Overall bending the curve has been a success, we’ve stayed below our capacity limits. But I’m not sure how long we can keep that up,” he said.

“In many ways, this pandemic is widening the fractures in the rural health care system and exposing the underbelly of the rural plight.”

This article was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.