As the novel coronavirus pushed American into sheltering at home in the spring, Travis and Staci Swiney were thinking about their future in Dickenson County, Virginia.

After the pandemic hit, Staci, 26, was partially furloughed from her job as a registered nurse at Clinch Valley Medical Center, while Travis, also 26, was busier than usual at the coal prep plant where he’d worked the last seven years.

The dynamic showed how the pandemic had strained institutions and called into question our assumptions about work in the future. Coal was supposedly on its last legs, beaten down by competition from natural gas and successive rounds of bankruptcies, while healthcare had replaced it as the biggest private-sector employer in counties across Appalachia.

In spring 2020, however, hospitals and clinics furloughed thousands of workers as they struggled with bans on non-emergency procedures and the need to conserve supplies for an anticipated coronavirus surge. Many coal mines shut down completely, whether due to bankruptcy, a sagging economy, or caution against spreading the virus, but enough remained in operation to keep Travis Swiney’s coal prep plant hopping – some governors in the region and even the federal government had deemed coal operations an essential service.

“As long as there’s a mine open and coal being produced, as long as they’ve got sales coming from somewhere, that will keep us in business,” Travis said.

Travis’s father went into the mines right out of high school, but was laid off after several years and went on to a second career in delivering PET Dairy products. Given the successive rounds of bankruptcy and layoffs over the last 10 years, the Swineys just assumed Travis’s job was at risk too.

“He’s always worried about his job, and what to do if he loses it,” Staci said. “We definitely are always on the lookout for another job for him, just because we know the coal business is not going to last, and there’s nothing here that pays even close to what he makes.”

Travis Swiney found his way into the coal industry because he “didn’t feel smart enough to go and get a high-paying job through college. I had to look for what would be a good high-paying job without a college education. There’s not much without a good education around here.”

Staci wanted to be a teacher, but her family discouraged her, saying that teachers weren’t paid well. “I went with what my family said, that nursing is the best option to make decent money,” she said.

She worked in a pre-operations unit, which was cut back with the pandemic’s furloughs. Staci thought about going back to school to train for a higher-paying job, such as a family nurse practitioner, but the pandemic has put a halt to that idea for now.

“We have a little boy, he’s 2, and I really don’t have the motivation right now to get back into school,” Staci said. “I definitely need to do it sooner than later. If [Travis] does leave his job, I do want to think about that.”

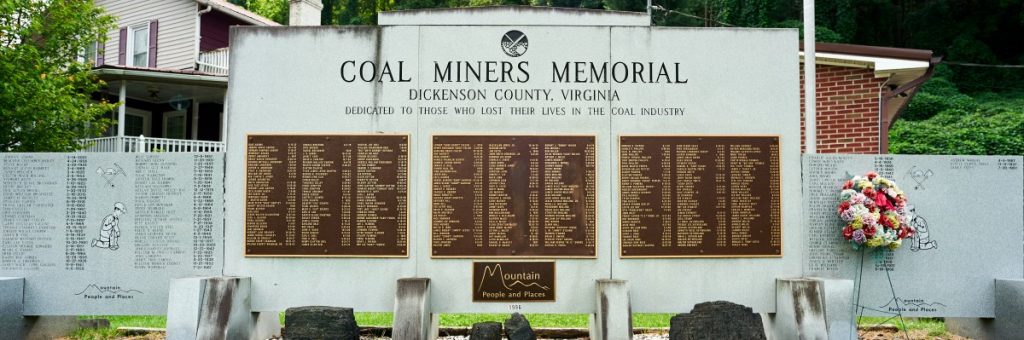

As the Swineys sit at a crossroads, so does their home county of Dickenson. A 100 percent rural area as defined by the U.S. Census, Dickenson County, Virginia, is home to nearly 15,000 people, 98 percent of them white. Three-quarters of the population has a high-school diploma and 10 percent a bachelor’s degree or higher. The disability rate is 19 percent, the poverty rate 25. It’s among four Virginia counties considered by the Appalachian Regional Commission to be economically distressed.

Dickenson County is also one of the roughly half of Appalachian localities to be classified as “distressed Americana” in the McKinsey Global Institute’s 2019 report, “The future of work in America.” Distressed Americana has a higher poverty rate than any other community segment, with seven of eight metrics rated as least economically favorable. No other segment has more than three of eight metrics rated that low. In a range of projections, McKinsey’s midpoint scenario shows job losses, not growth, through 2030 for most “distressed Americana” localities like Dickenson County.

Like its neighboring counties in southwestern Virginia, Dickenson never fully rebounded from the Great Recession of 2008. As the rest of the country embarked upon the longest running bull market in history, Dickenson County was pulled down by a failing coal industry that suffered successive rounds of bankruptcies, layoffs and closures. With no metro area in close proximity, there’s no focus point for businesses to cluster.

How can a place like Dickenson County prepare for the future of work when it’s fallen behind the present?

In his comprehensive history of Appalachia, West Virginia historian John Alexander Williams argued that, “[i]n the new terrain of globalized market capitalism, the combination of exploitation and per-/re-sistance, of crisis and renewal, that Appalachian history manifests may turn out to be instructive to every dweller in the postmodern world.”

In other words, what’s happening in Appalachia isn’t just important for people who live here to recognize and learn from, but for everyone who sees the parallels between the region’s extractive historical patterns and those playing out around the world.

Certainly, history features prominently among the group of Dickenson County residents actively building a new economy.

Grant Belcher, a 31-year-old social-media guru who develops and runs Facebook pages for county businesses and marketing campaigns, introduced himself as a “10th-generation Dickensonian, a descendent of both of the founding immigrants” to the county. Belcher likes to tell of the history of Haysi, a coal town that did not belong to operators but was run by small merchants who set up there because of its location on the Clinchfield Railroad.

“The economic future of Dickenson County is mostly in the northwestern part of the county, specifically the Haysi area because of its proximity to Breaks [Interstate Park] and the Buchanan County line,” Belcher said. Across that county line is Poplar Gap, a former Alpha Natural Resources surface mine that’s been developed into a county park with athletic fields, a water park and a golf course. The park also sits at a major hub on the Spearhead Trails, a network of off-road ATV trails.

“The biggest reason Dickenson County has a bright future is we have not been discovered,” Belcher said. “We may not burgeon to be at the level of patronage the Smokies have had, but I don’t care about that. The only thing I care about is a steady slow increase and a sustainable economic future, not a flash in the pan.”

Belcher works as a third-generation insurance agent, but as a volunteer, he’s also developed a Facebook marketing campaign for Dickenson County. He created town and county marketing accounts as well as points of interest like the Russell Fork River, or the “Grand Canyon of the South.”

Belcher also networks with businesses and artists to help them develop Facebook pages and collaborate on sharing content. Belcher, a libertarian who also operates the “Open Kerry” blog on politics, culture and religion, said the volunteer project has no connection with government marketing initiatives.

“What I’ve found out in my five years of doing this is you don’t need professional quality to be effective,” Belcher said. “There are more than enough people out here right now who are taking decent, effective cell phone photography. We’ve got a very core, passionate culture here that goes back to sports and school programs. People from Haysi love Haysi.”

Summer Mullins-Runyon, 43, also has deep roots in Dickenson County, going back six generations. Her father was a coal miner and her mother an elementary school teacher. She has worked in medical billing her whole life, and her husband is a utility worker for Verizon. Mullins-Runyon launched the first Airbnb in Dickenson in 2014, which was open until last year. Like Belcher, she created a social media account to promote the region. The “VA’s Baby” account on Twitter and Facebook references the fact that Dickenson was the last county to be incorporated in Virginia.

“My generation wants to see something done,” Mullins-Runyon said. “We’re speaking out, everyone has all these ideas, but there’s no money. My daughter will be 17 in a few months. The only things she has to choose from are being a teacher, working in healthcare, or a social service-type job — just the basic necessity things that rural counties have left. She wants to stay here. That amazes me.”

At one point she made a list of the nearly 100 people with whom she’d graduated high school in 1995. Of them, only one went to work in coal, and he’s since left the job. Many more work at Red Onion State Prison, a supermax facility that opened in 1998, or Wallens Ridge State Prison, which opened a year later.

“A lot of people I graduated with went to work at Red Onion when it opened, and are still there,” Mullins-Runyon said. “It really gave people that didn’t necessarily want to go to college a place to work. [Without it] they probably would have went into the coal mines or moved, I totally know that. But then again it was detrimental to this community in a way. That’s a very high stress job.”

Shortly after it opened, Red Onion prison was cited by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International for practices that violated the human rights of prisoners held there. Since Red Onion and Wallens Ridge opened, other coalfield communities have wrestled with the pros and cons of federal and state prisons, which have become pandemic hotspots. In Letcher County, Kentucky, the community organized to successfully prevent construction of a federal prison in the name of economic development.

In Dickenson County, the prisons are big employers. But there’s a cost to working there.

“At the time [they opened], it was, ‘Oh my gosh, there’s an alternative to going into the mines. We’re going to take this job,’” Mullins-Runyon said. “They had no clue how mentally stressful that is. The guys I know who worked there, it changed them. They’re still there. It’s just like the coal mines. It’s good benefits so they stay.”

But really, Mullins-Runyon said, they have no alternative.

The challenge of developing that alternative faces Josh Evans, a lawyer who at 34 is the youngest member of the 5-member Dickenson County Board of Supervisors by decades. Evans was elected to the board in part by arguing that “we need to do anything we can to create any kind of jobs that we can.” Evans generally gets along with the other board members, but his urgency has created some tension.

“We have different viewpoints on how we go forward,” Evans said. “Some want a slower pace and I want more aggressive action, on just about anything period.”

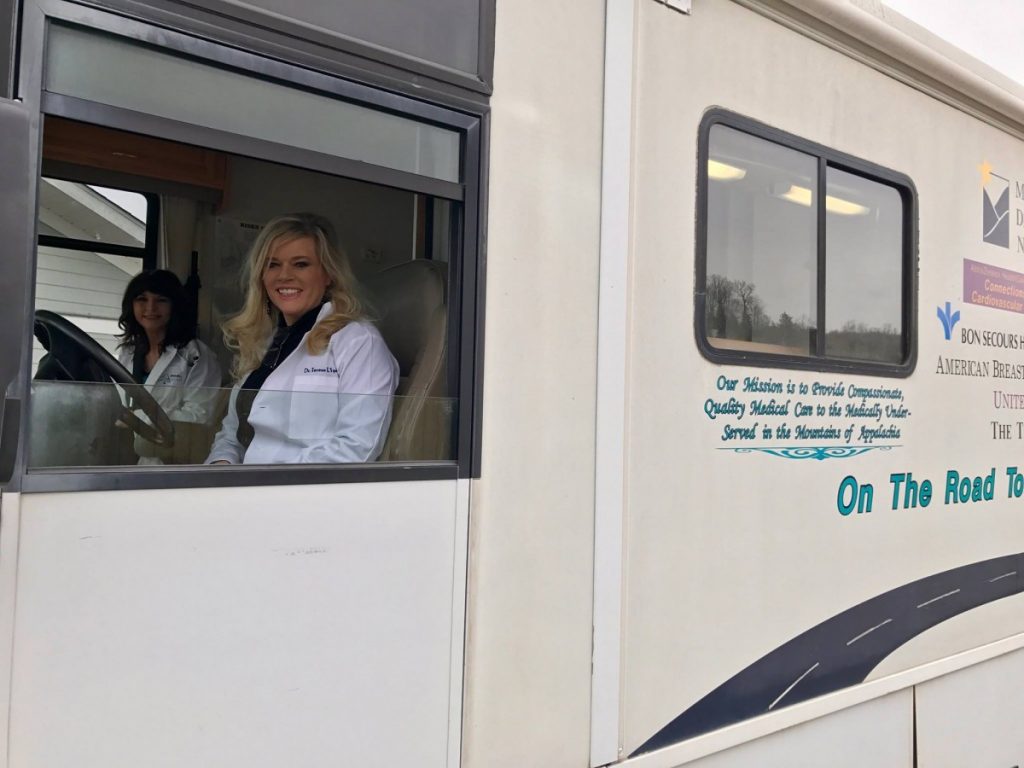

But figuring out where to start can be daunting. Dickenson County shares with central Appalachia an especially rugged geography that spreads people out and makes it hard to maintain infrastructure, like broadband internet and cell service. Healthcare is difficult, too; although places like the mobile free clinic Health Wagon are expanding into permanent facilities in Dickenson, residents have to travel out of the county for specialists or hospital stays.

“Obviously, the big issue is transportation,” Evans said. “I don’t know there will ever be proper entry and exit out of Dickenson. But at the same time, I don’t know [that] we can waste time talking about it. There’s nothing we can do to make the Coalfields Expressway come any quicker.”

Because of the expense of road building and difficulty in attracting funding in a state that’s also eyeing road expansions in metro Washington, D.C.. Evans said the best thing the county can do is to focus on building broadband internet. That could help attract data centers, which don’t employ many people but create tax revenue, and would enable more people to work remotely as well as help small businesses grow.

“We can dream about the factory coming from now until doomsday, but the factory’s not coming,” Evans said. “We have to work with what we have and try to grow ‘em. I hate to say that — I’d love to see a manufacturing plant come — but long term and realistically, where we need to focus right now is our small business people.”

Dickenson County played an important role in Virginia’s once burgeoning coal sector. It played a pivotal role in the Pittston Coal Strike of 1989-’90, which in many ways marked a final stand for union mines in the state and region. The strike certainly shaped the views of generations like Mullins-Runyon, who came of age in the ‘90s determined not to go into the mines. Thirty years later, the reality that coal belongs more to the past than the future has been confirmed, but places like Dickenson County still face an unanswered question: What’s next?

“This part is really unclear as to how it’s going to move forward,” said Jason Hong, a professor in Carnegie Mellon University’s Human Computer Interaction Institute. “On one hand, remote work makes it possible to do these info tasks anywhere in the world, but on the other hand, there’s a growing trend of people moving to cities because there are more opportunities, not just for jobs but socially too. Urbanization is almost certainly going to continue, which will leave smaller, rural communities in a serious bind as to what their futures will be. That’s a really big question that nobody has an answer for, unfortunately.”

But Hong took a swing at answering, anyway. Part of the answer must come from national policymakers and be aimed at finding ways to encourage more widespread revenue sharing, he said, whether through trade protectionism or finding ways to more evenly distribute prosperity.

Local communities must step up as well.

“Complacency just isn’t going to work anymore,” Hong said. “It seems like people wish the world would go back to the 1950s, when the U.S. was dominant and workers only needed a high-school education. That’s never going to happen again. This is going to take community leaders being really honest and willing to experiment a lot to figure out what is unique about their communities that they can leverage.”

In her essay, “So Goes the Nation: Southern Antecedents and the Future of Work,” historian Bethany Moreton argued that the South — and by extension, Appalachia — never really fell behind the rest of America, but in many cases actually “leapfrogs over industrial liberalism to connect a plantation political economy to a digital age.”

Basically, the South’s historical pattern, from plantations to coal mines to non-union factories is more the norm for American history than the relatively brief period in the mid-20th century when workers could get good pay and good benefits at a secure job. Certainly, the Southern pattern of extraction from land and labor can be found frequently throughout Appalachian history.

Moreton points to the legacy of coal in Appalachia, where communities that built their culture and economy around extraction have been stripped bare, leaving behind poverty, poor health outcomes and greater dependence on government for basic services.

“If we could not find it in ourselves as a nation to do better on the basis of what was happening locally to people in places like Appalachia, then the joke’s on us,” Moreton said. “It wasn’t happening only to those people; it’s happening to all of us. History proves over and over again that, even if you thought that that bargain was somehow justifiable on some moral ground, you can’t actually contain the harm.”

Contrary to popular stereotypes, Appalachia never fell behind the rest of the world. Instead, the exploitation of the region by extractive interests and the history of its people fighting back and carrying on through adversity charts out the future.

This story is part three of a three-part series on the future of work in Appalachia. Read more from the project Disrupted here.