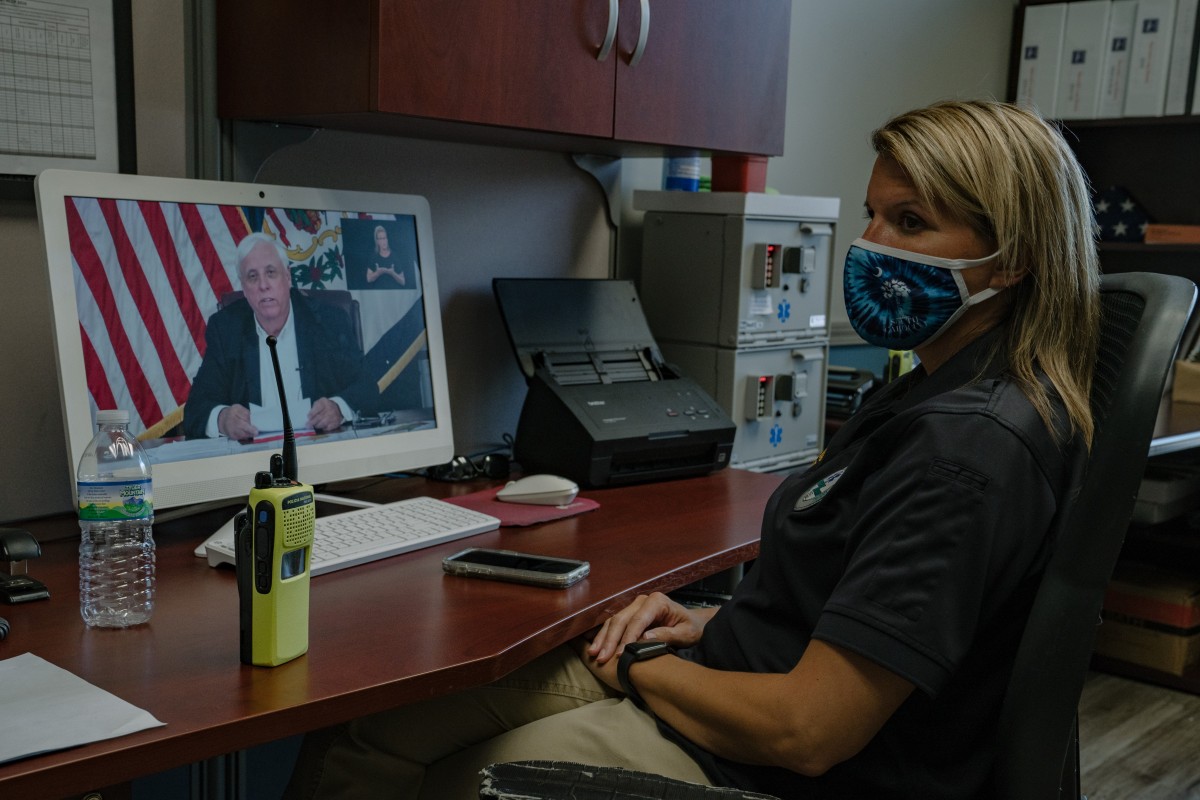

As the global COVID-19 pandemic spread into rural communities earlier this year, states like West Virginia watched the number of emergency service calls drop as public spaces shut down and more people were either required or chose to stay at home.

In the early months, suspected COVID-19 calls trickled in for the state’s EMTs and paramedics, but West Virginia’s total infection numbers stayed low, and one medic in Marion County in north central West Virginia said they went four days without a single emergency call.

But in May, “a light switch went off,” as one medic tells it. Call volume skyrocketed, then leveled out to near pre-COVID numbers for this time of year.

This surge in calls, however, was not entirely due to COVID-19; it appears to have been driven by an increase in medical emergencies common in West Virginia – motor vehicle accidents, elderly health problems and drug overdoses.

There were twice as many drug overdose calls in May 2020 as there were in the same month of 2019 and almost 100 more cases this June than last year, and now, into August, Marion County EMTs and paramedics continue to respond to drug related emergencies on an almost daily basis.

Substance use and misuse does not happen in a vacuum, however, and emergency responders were quick to point out that the surge in overdoses went hand in hand with the dismantling of rehabilitation centers and mental healthcare providers in the area.

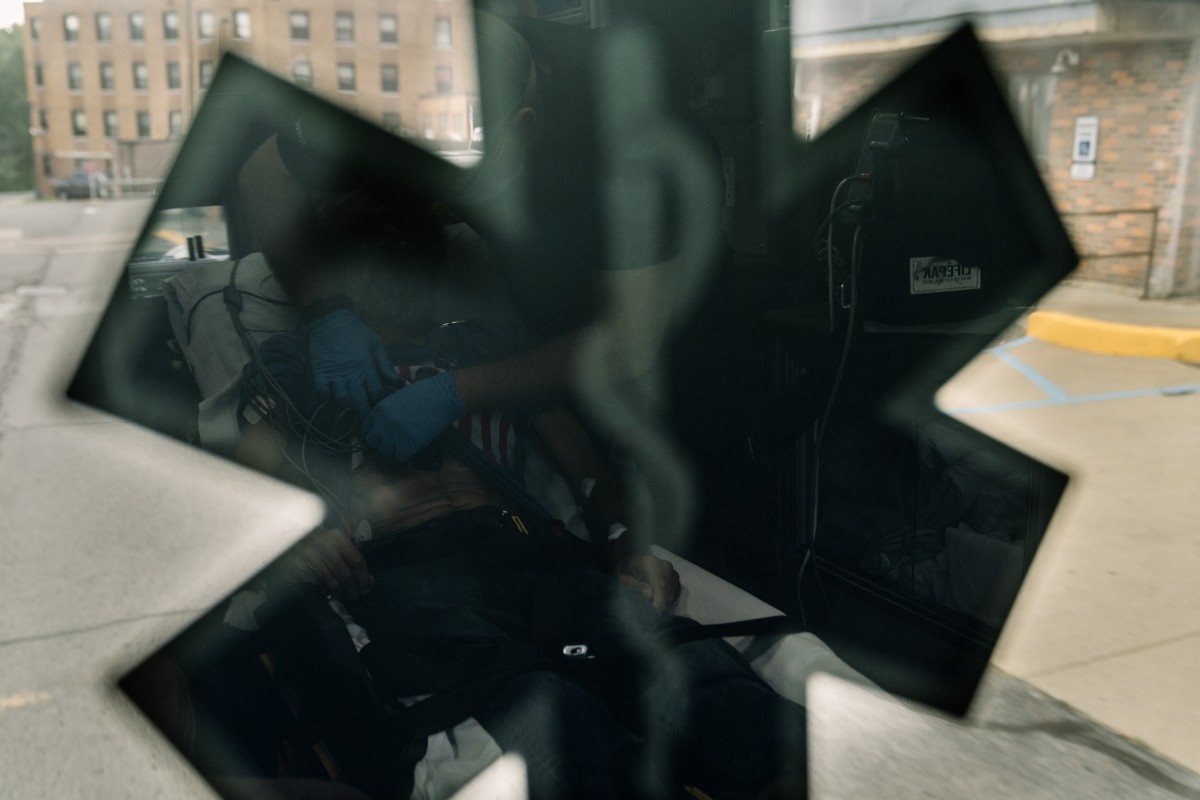

On an afternoon in early August, a call came in to the Marion County Rescue Squad for an unresponsive patient. After reading off the address, the dispatcher added “COVID positive,”– and the ambulance crew exchanged knowing glances as they rushed to their truck.

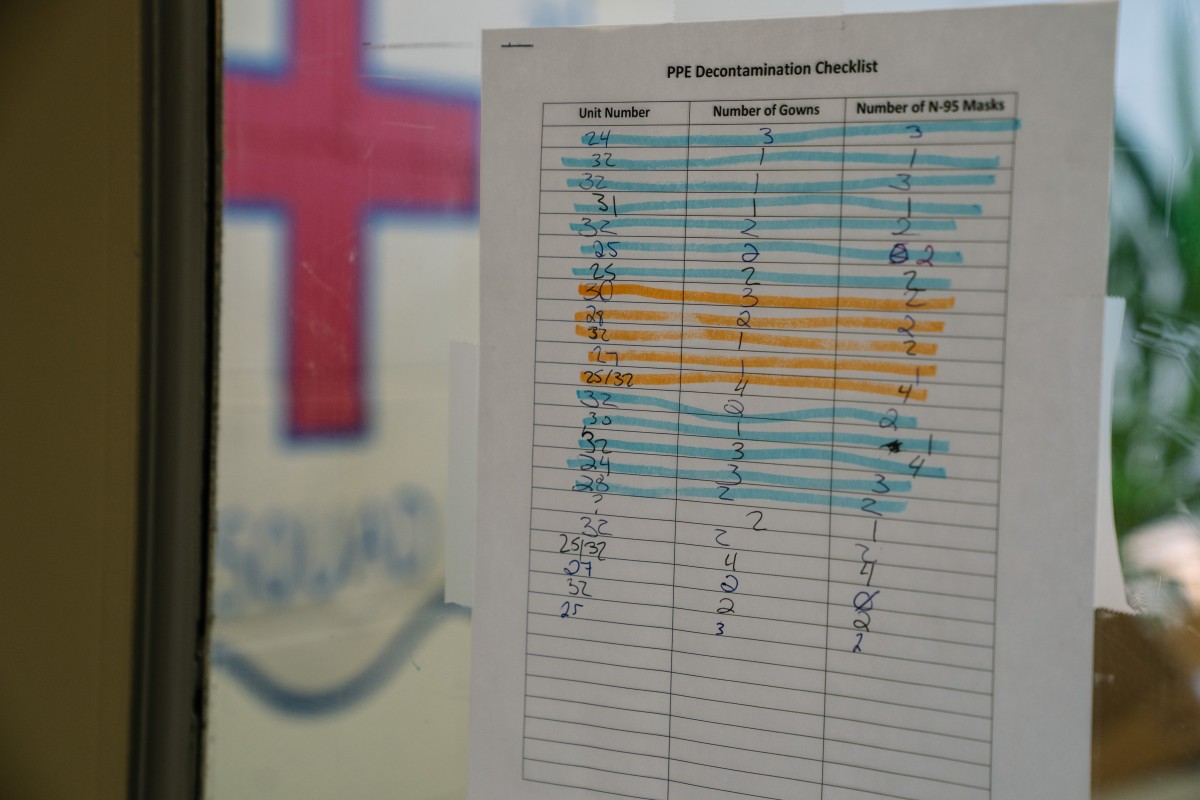

Unresponsive could mean anything from cardiac arrest to simply asleep, and on top of the thousands of last minute calculations and mental preparation for the call to come, the EMT, paramedic and paramedic student onboard made sure their extra PPE, or Personal Protective Equipment, was ready to go.

As the ambulance approached the house, the driver yelled, “hang on,” and barreled up the gravel driveway.

The additional cost of COVID-19 PPE impacted EMS services across the state. Most emergency services in West Virginia are provided by private companies with little to no government funding, leaving the companies to chase down insurance providers for payment.

In Marion County, the medics poured out of the ambulance with quiet urgency, grabbing medical gear and rushing towards the front porch.

A relative of the patient had seen the patient inside, but the front door was locked. The crew rushed to a side window as they donned gowns and safety glasses. They pried open the window, pushing the screen out of the way before shoving the paramedic student through the window head first to let them in the front door.

Once inside they quickly assessed that the patient had passed away hours earlier.

“He’s DOS,” the paramedic student quietly confirmed: Dead On Sight, requiring a call to the county medical examiner and police.

EMS work is often dirty, tedious and grim. Perhaps nothing encapsulates this more than hours of waiting on scene for a medical examiner to allow the body to be moved to a local funeral home.

Unable to remove their PPE, the medics waited outside as the family member talked herself through the logistics of dealing with the patient’s death – coordinating family travel, cleaning the house and wondering aloud at whether she may be infected with COVID-19 as well.

One paramedic admitted that the constant exposure to death both in its most gruesome and tranquil forms impacts everyone who works in emergency services, and it can take a constant effort to remind themselves to remain human on the job.

As first responders, EMTs and paramedics are often present for the worst moments of someone’s life, and patient care means far more than knowing the correct medical procedure to administer. It means being able to read between the lines of the woman who was found asleep in her vehicle by law enforcement at a gas station, coaxing an admission that she hadn’t slept in two days due to methamphetamine usage. It means being able to tell the anxious daughter of an elderly woman how to best coordinate with her mother’s doctor on the way to the ER, or calming down the anxious pregnant woman with the elevated heart rate by swapping stories about tattoos.

In Marion County, like many rural areas in Appalachia, working in EMS often means wearing more than one hat. It’s common for EMTs to work as firefighters or be trained in rescue operations, and one EMT at the station said he’s both a firefighter and serves as a municipal judge in addition to his job on the ambulance.

For the three days I spent with the Marion County Rescue Squad, almost every patient expressed confusion about whether or not Fairmont’s local hospital, recently closed and reopened under WVU Medicine’s management, was closed. Taking a patient there versus the other hospitals in the area is a 10-15 minute difference, and bypassing the closest available ER meant an additional charge to the patient’s insurance provider (if they have insurance in the first place).

But Fairmont’s hospital lacks the specialists needed for more serious emergency situations, which require a second ambulance ride to another hospital. The decision of where to transport a patient has to be made in minutes – sometimes seconds – and the EMTs and paramedics calculate this and countless other variables over and over again in a single shift.

Two hours after the ambulance first arrived on the scene, Marion county’s medical examiner Matt Smith arrived.

“No pictures of the body,” he reminded me as he donned his own gown and mask while the medics prepared a white body bag, ensuring a final measure of sanctity and respect for yet another life lost during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a matter of minutes, the body is loaded into the back of the ambulance, the patient’s relative illuminated in the tail light as we bumped back down the driveway to a local funeral home.

Watching Smith and the EMS crew maneuver the body onto the stretcher was a poignant reminder that the men and women of Marion EMS guide the county’s residents back to life, and on countless nights like this one, have provided a solemn final escort to death.

Chris Jones is a Report for America corps member covering domestic extremism for 100 Days in Appalachia. Click here to help support his investigative reporting through the Ground Truth Project.