Though employment is still down across the board, rural recreation counties are bouncing back from the pandemic faster than urban ones. In Haywood County, North Carolina, small businesses face their challenges with determination and passion.

When all non-essential businesses in Maggie Valley, North Carolina, were forced to shut down for eight weeks at the beginning of the pandemic, Momma T’s Mountain Made art and craft store struggled to stay afloat.

Momma T’s, a small shop selling jewelry, crochet and other artisan souvenirs in a tourism-driven town of 1,541 residents in western North Carolina, wasn’t awarded any federal small business assistance during the shutdown. Zoe Snow, co-owner and daughter of the shop’s namesake, explained how until early July when they finally received a loan, not only did the store dig into its own savings in order to keep above water, but that she also had to make personal sacrifices to keep the business alive.

“I was paying for everything from my unemployment that I was receiving,” Snow said of the store’s fixed expenses. “I actually ended up using my stimulus check for rent for this place while we were shut down.”

Now, as visitors return to Maggie Valley and summer tourism reappears masked but mighty in the mountain region about 35 miles west of Asheville, Momma T’s is actually doing better than it was at this time last year.

“We ended up losing 93 percent of our income during the closure,” Snow said from behind the plexiglass installed at the checkout desk. “Right now, we’re actually up about 30 percent from last year’s sales on almost any given day.”

Momma T’s is just one of many mom and pop businesses in small towns across America that nearly went under when COVID-19 response measures mandated closure of all nonessential businesses. But through resilience, adaptiveness and in some cases, the good fortune of being declared an essential business, some small businesses in rural recreation areas have recovered and are doing better than expected.

For Snow, adapting to the new normal meant making jewelry in her small home studio and relying on a few internet sales of items they had in stock. Survival for the shop was a matter of timing. “We hadn’t done all of our summer shopping yet, inventory wise, so we still had some savings,” Snow recounted.

Hilda Rios is the manager (and margarita maker) at Los Amigos, a classic-style Mexican restaurant in the nearby town of Waynesville, North Carolina. She is also the daughter of the founder and chef, cousin of the waitress, and sister-in-law of the bartender. Rios attributes her 13-year-old family business’s success during the pandemic to the quality of the food, the business acumen of her father, and their proactive approach to keeping business strong during every phase of reopening.

“During Phase One, we did takeout orders every single day,” Rios recounted of the weeks where North Carolina restaurants were still closed for dine-in. Now in Phase Two, even at half seating capacity indoors and with a flooded patio area due to a recent storm, business is still surprisingly strong at Los Amigos.

“Actually business is better right now than this time last year. We have 50 percent more business right now. We have no idea why it’s happening— it’s the same people who always come in, both locals and tourists— but we’re so thankful,” Rios said.

For some other small business proprietors and experts in rural economics, the reason for the apparent bounceback is not as mysterious as it seems.

Douglas Christopher of Christopher Farms in Waynesville says that the silver lining to the pandemic is rather obvious for businesses that are deemed essential. For his family’s 33-year-old standing farmer’s market, his storefront sales have increased despite the shutdown of other businesses.

“Actually, the situation has helped essential [grocery] businesses tremendously,” Christopher explained. “People are starting to realize just how expensive it is to eat in restaurants and are learning the value of making meals at home. You can make a pizza for $3 at home, or pay $22 for a pizza at a restaurant.”

That being said, a substantial chunk of business for Christopher Farms comes from providing to local restaurants. Christopher said that with many of these local restaurants shutting down or reducing capacity, his business has been hurting on the food service front throughout the pandemic.

It seems to come down to whether a business is deemed essential and how adaptable its owners can be. The owners of La Mexicanita, a small Latino food store in Waynesville, explained how this dynamic played out for their two distinct businesses.

“We were deemed essential because we sell groceries, and so we’ve been doing well in this store. But we own another business, a party [Western] attire business, and that business has been so low,” the husband-wife duo explained in an interview in Spanish. “We’ve been closed there for some months. We hope we’ll be able to reopen it soon, but it all depends on the regulations that come out about whether the parties and gatherings can happen again.”

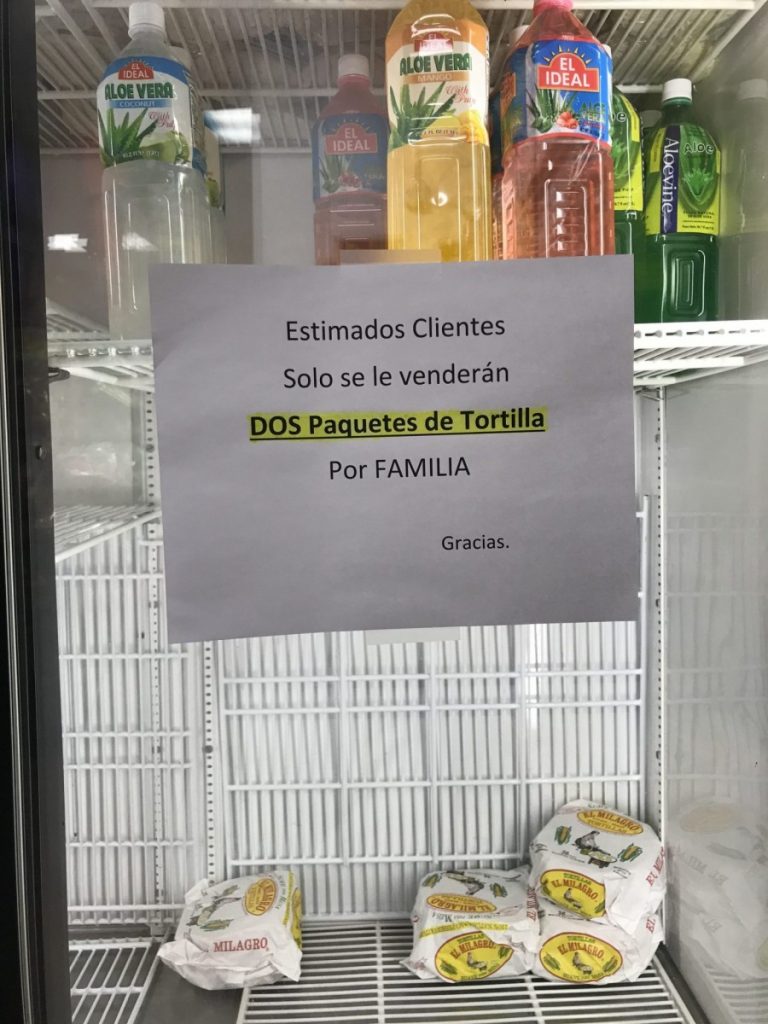

In La Mexicanita, the store owners’ adaptiveness to the pandemic response is noticeable from the moment one walks in the door. From limits on the number of packages of tortillas families can purchase, to clear, lidded boxes filled with pastries that would normally be on display, to the owners handing out disposable masks to patrons who come in without any face coverings, the owners of La Mexicanita are serious about staying open, which means they’re serious about compliance.

For counties with economies based on recreation, the source of tourism seems to play a role in whether business has picked up. According to Megan Lawson, Ph.D., of the nonprofit research group Headwaters Economics, the pandemic has put the road trip back in style.

“My hypothesis is that [for] the tourism and visitation that would usually be happening in urban places in the summer, like ‘hey, let’s take a family trip to San Francisco or New York,’ people are reconsidering those choices and going to less populated areas,” Lawson said.

Although she doesn’t yet have the data to confirm it, Lawson predicts that especially in the national parks, while international tourism dipped, domestic and drive-in tourism may have increased to fill the gap.

“These communities are recovering more quickly than we expected. I think we weren’t anticipating all this pent up demand from when people couldn’t travel,” Lawson explained. “Now all of a sudden it was like America was shot out of a cannon into the rural parts of the country.”

This is consistent with what Snow has seen so far this season: no international visitors that she knows of, and many road-trippers.

“We’re still getting a fairly diverse group,” Snow said. “It seems like right now… we have a lot of driving traffic. I don’t think we, personally, get a lot of plane traffic people. … We get most of our tourism from Florida, South Carolina and Georgia.”

Despite the obstacles, rural recreation areas seem to be faring better overall than their urban counterparts. According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics compiled by the Daily Yonder, employment is down by an average of 11.3 percent across all recreation counties in the nation from May 2019 to May 2020.

Yet rural (or nonmetropolitan) recreation counties are suffering less of the blow. Employment in rural recreation-focused counties is only down 10.7 percent since last May, whereas recreation counties in urban America have seen employment drop 12.5 percent in the same time frame.

Similarly, since restrictions have been lifted, rural recreation counties’ employment rate has performed better in the short term than that of urban. From April to May, urban recreation counties saw only a 4.1 percent increase in employment, whereas for rural recreation counties, employment increased by 6.9 percent.

This all takes place in the context of recreation-related employment leading the overall employment resurgence in the country. According to a recent Bureau of Labor Statistics report, “In June, employment in leisure and hospitality increased by 2.1 million, accounting for about two fifths of the gain in total nonfarm employment. Over the month, employment in food services and drinking places rose by 1.5 million, following a gain of the same magnitude in May. … Employment also rose in June in amusements, gambling and recreation (+353,000) and in the accommodation industry (+239,000).”

But recreation counties are not out of the woods just yet when it comes to the economic damage that COVID-19 will cause. Recreation counties — both urban and rural — suffered the largest dip in employment compared to all other county types since last May.

Lawson explained that the seemingly great resurgence of jobs is partially attributable to the unexpected growth in rural tourism, but mostly a result of the steep fall those numbers took at the beginning of the pandemic.

“What’s more likely going on is that those jobs went to zero during the most strict part of the lock downs,” Lawson said. “So it’s easy for them to have a very dramatic increase from zero.”

Lawson is particularly concerned about the effect of all of this on seasonal workers in rural recreation towns who already live paycheck-to-paycheck lifestyles and face other hardships, like unaffordable housing for working-class people in resort towns.

“My biggest concern is what’s going to happen to those folks, because that’s going to determine how well businesses can stay open: if they can actually find people to work there,” Lawson said.

Rural recreation counties are still deep in the unemployment hole, and as increasing case counts around the country raise the specter of a second wave of shutdowns, small businesses in rural areas are gritting their teeth for another round of hardship.

“This has definitely eroded [small] businesses’ future ability to be resilient,” Lawson stated. “I think those smaller businesses don’t have the cushion that big box stores do. The effects haven’t fully materialized yet of the uncertainty, of the roller coaster that the small businesses are trying to ride right now.”

Small business owners in recreation counties agree that it’s been tough, but they are determined to make it through.

“We’re used to just making stuff work,” Snow from Momma T’s said. “A lot of people around here, definitely, we’re used to picking ourselves up by the bootstraps.”

This piece was originally published by the Daily Yonder.