Kacie Boone, a rising senior at East Rockingham High School in Elkton, Virginia, never considered herself to be an activist.

“It’s kind of new,” Boone said. “I’m not like a — I hate the term — ‘social justice’ type [of] person.”

But in June, that changed for the 17-year-old when she said the wave of protests following the May 25 killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white police officer in Minneapolis pushed her to act.

Soon after, Boone decided to organize her first demonstration supporting the Black Lives Matter movement that was taking to the streets of big cities and small towns across the country.

With the help of Tsion Ward, a senior at Spotswood High School, in nearby Penn Laird, Virginia, as well as other students from across Rockingham County, Boone’s demonstration was held at Stonewall Memorial Park in Elkton, Virginia, and called on leaders in the Rockingham County School District to recognize the systemic racism built into their culture. The students presented district leaders with a list of demands, including requiring anti-racism training for all students and staff, creating a streamlined system for handling complaints of racism, banning Confederate symbols as part of the dress code and removing police officers from schools.

“[Just] because we’re a small town or we have Harrisonburg High School — which is a very diverse school — doesn’t mean that we’re exempt from injustices,” Ward said. “We wanted to hold everyone accountable, especially school officials and administrators.”

Boone and Ward’s activism caught on in other parts of southwest Virginia, and more and more high school students started to organize, calling on their district leaders to make similar changes. Molly McPherson, a rising senior at Blacksburg High School in Blacksburg, Virginia, was among them.

“Our dress code has a ban on symbols of Black power,” McPherson said. “So, students are not allowed to wear the Black power fist or anything like that. But nobody knew that, so nobody was fighting it.”

According to the Virginia Department of Education, Black students are disproportionately suspended compared to their non-Black peers in the state. In counties with fewer Black students and teachers, like those in southwest Virginia, that disparity only grows.

Virginia is a left-leaning commonwealth with two Democratic senators in Congress and a Democratic majority in the state’s General Assembly. The governor, lieutenant governor and attorney general are all Democrats. However, it was only recently that Virginia changed from a swing state to a blue state, and Republicans maintain a strong hold on the less populous regions of the commonwealth, particularly in the southwest.

But the activism being seen there today isn’t new, in fact, rural Virginia has a rich history of student-led activism.

A ‘Deeply Segregated System’

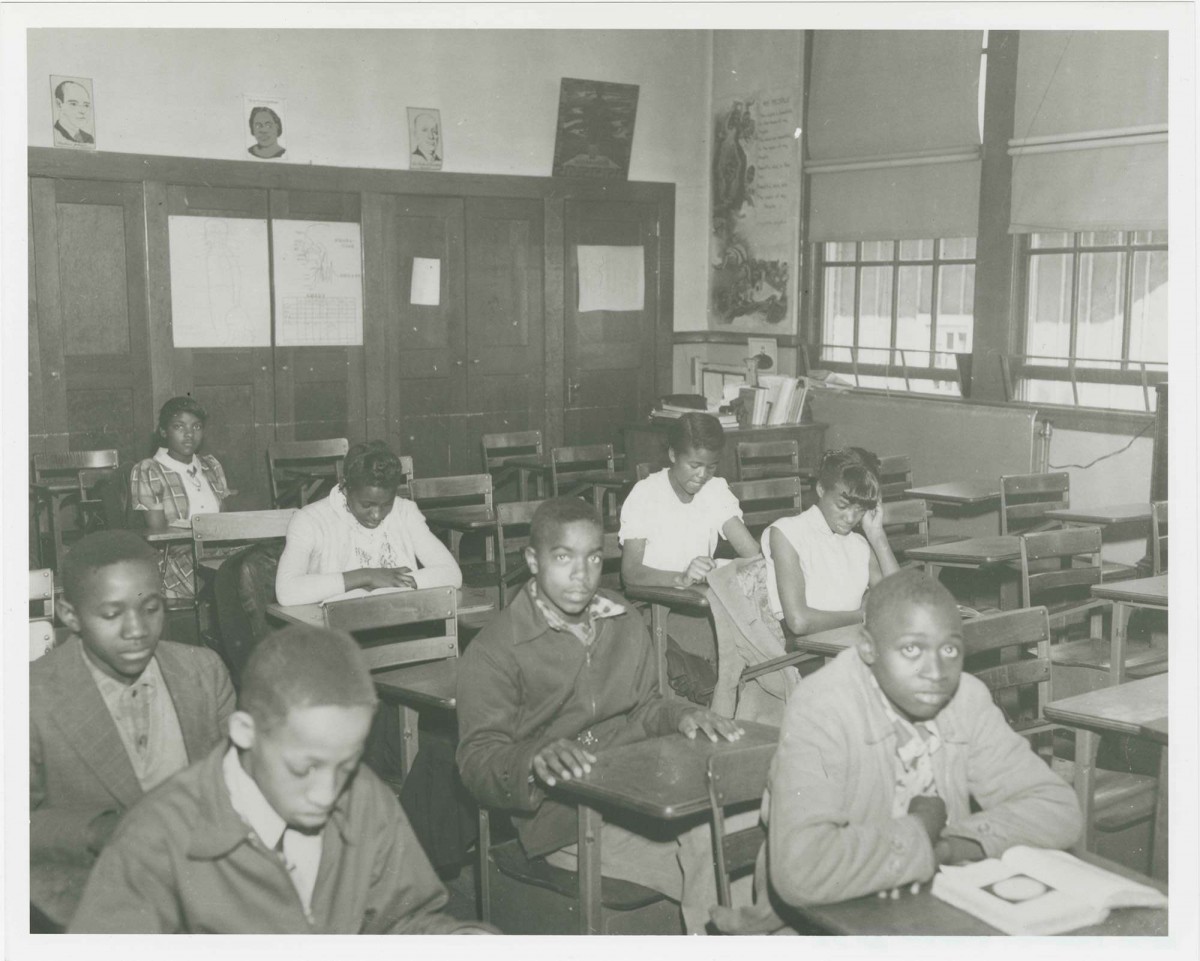

During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ‘60s, students in rural parts of Virginia led walk-outs and protests over inadequate facilities. Places like more rural Danville and Farmville were hubs for activists.

Moton High School in Farmville was the site of a 10-day-long student strike in 1951 led by then 16-year-old Barbara Johns, with assistance from fellow student John Stokes. Stokes — who later wrote “Students on Strike: Jim Crow, Civil Rights, Brown and Me” — recalls a system so deeply segregated in rural Virginia that it was difficult to conceptualize an integrated society.

“All we wanted was a new building,” Stokes said of the protest movement he helped begin in 1951. “We did not want integration because we loved our teachers. We loved where we were at that time, but they would not give us a new building.”

The strike led by Stokes and Johns led to a lawsuit filed by the NAACP on behalf of a number of Black families in Prince Edward County under the name “Davis v. County School Board,” named for Dorothy Davis, another student involved in the protest and the first plaintiff listed on the court filings. The NAACP lawyers argued in favor of desegregation rather than the new but separate accommodations students like Stokes and his classmates wanted.

The case worked its way through the court system and was eventually combined with four others in front of the U.S. Supreme Court under the name “Brown v. Board of Education.” The Supreme Court unanimously held that segregation was inherently unequal and therefore unconstitutional, changing the way public schools across the country would operate – no longer separated based on race.

However, pushback against school integration was all too common in rural Virginia, like in many communities across the country at the time. Schools shut down to avoid integrating, and many students were not able to get an education for years. This prompted a new wave of protests.

“There was a delegation of students who had been locked out [of the schools] that staged strikes in Farmville, and they were working on breaking the economic back of those staunch segregationists [with their strikes] who were voting to keep the schools closed,” said Dr. Amy Tillerson-Brown, a professor and chair of the history department at Mary Baldwin University in Staunton.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, the students who demonstrated for racial equality were met with the wrath of local white supremacists, Tillerson-Brown said.

“If you had the audacity to speak out and suggest that you deserve equity, it could be a death sentence for you,” she said. “In fact, the … KKK burned a cross on the lawn of Moton High School soon after the student strike.”

That student was Barbara Johns, who was sent to live with her relatives in Alabama after the cross was burned in front of her house.

Eventually, change did come to rural Virginia. Schools were reopened and fully integrated by the 1970s. But the more things change, the more they stay the same, Tillerson-Brown said, and issues of racial inequity remain in the school system. Young activists across rural Virginia, perhaps without even recognizing it, are expressing a similar sentiment today and Tillerson-Brown believes their demands and refusal to be placated by empty measures is actively bringing change.

“Had it not been for those protests, riots, whatever you want to call them, I don’t believe that Derek Chauvin’s third degree murder charge would’ve been moved to second degree, as it is now,” she said, of the police officer charged in Floyd’s death. “It’s going to take the youth to make change.”

Stokes is also glad to see today’s youth in rural Virginia continuing the fight and believes that the current multiracial coalition of protesters is strong enough to bring change.

“If we’d had the white kids to walk out with us in 1951, we would’ve won our case without even going on to the Supreme Court,” he said.

A Continuing Movement

Like the students of the Civil Rights Movement, today’s young activists say they are also “sick and tired” of the injustices they both see and experience in their schools and communities. They want to see local governments and school boards take action to protect people of color and provide them with equity.

Kolby Brown, a senior at Christiansburg High School in Christiansburg, who helped Molly McPherson organize a demonstration of their own, is optimistic that her school board will pass policies to protect students and teachers from racism. Brown and McPherson are asking their board to re-examine that schools’ dress codes, create anti-racist training programs for teachers and change the schools’ disciplinary polices that disproportionately punish Black students.

“It will definitely take time,” Brown said. “We have the school board’s attention. I think, since they see that the community’s come together to support this cause, they will start making change.”

There also remains a threat to anti-racism protesters. Ward and Boone faced threats by local white supremacists because of their rally in Elkton, causing them to cancel their planned march and host a sedentary rally instead. They also sought assistance from activists in nearby Charlottesville. “They’re risking life and limb,” Tillerson-Brown noted.

“We’re going to keep fighting until there’s action, because, to me, words are meaningless unless you back them up with action,” McPherson said. “So far, we’ve seen nothing, and I think our ultimate goal is to see physical changes in our school and school system.”

Boone and Ward haven’t seen results for their calls on school leaders just yet. Rockingham County Public Schools Superintendent Oskar Scheikl told 100 Days in Appalachia that while he “understand[s] the enormous concern of what has been called the ‘school to prison pipeline,’ it has been a stated goal of RCPS to work toward educational solutions to code of conduct violations, and our SRO’s are part of that conversation” – meaning it’s likely that officers will not be pulled from the district’s schools as students have demanded.

Still, Boone and Wardsay that they are taking precautions and will not be deterred from their activism.

“We’re really not done,” Boone said. “This is the beginning of us trying to make our community more inclusive to people of color.”

For now, the protests led by students in rural Virginia continue. When asked if she has any advice for this new generation of civil rights activists, Tillerson-Brown offers this:

“Stay woke. And if you’re not woke, get woke.”

Sally Dukes is a recent graduate of Virginia Tech with a degree in political science and was formerly a columnist at the Collegiate Times. She currently lives in Charlottesville, Va. and writes whenever she has the chance.