The piece was originally published by Ohio Valley ReSource.

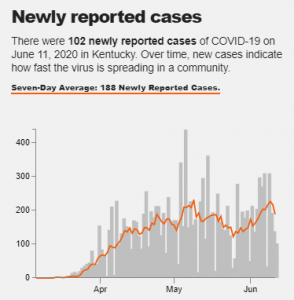

As the economies of the Ohio Valley gradually reopen from the pandemic closures, state officials are still reporting hundreds of coronavirus cases each day in the region. In Kentucky, coronavirus cases are again on the rise, with a week-long average of daily cases approaching the highest level yet. Public health officials are concerned about a spread of coronavirus into more rural parts of the region.

“I’m really worried that the second wave of COVID, as we come back open again, is going to hit rural America much harder than the first wave,” Dr. Clay Marsh said. Marsh, who is vice president of West Virginia University Health Sciences, has been leading coronavirus protection efforts in the state.

For many rural counties, the spikes in case numbers have stemmed from a few kinds of facilities and workplaces where COVID-19 has spread like wildfire: meatpacking plants, prisons and nursing homes. Protecting rural communities, where many people are especially vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19, will largely depend on controlling the spread in those facilities.

Meatpacking Plants

“The problem is without a vaccine, there is no path to recovery, that there’s nothing normal about going to work and having to wear a mask and having your temperature taken,” said Caitlin Blair, spokesperson for United Food and Commercial Workers Local 227.

Blair’s union represents workers in several meatpacking plants throughout Kentucky and southern Indiana where some workplaces have been rocked by soaring coronavirus infections, driving up case numbers in the counties where they’re located.

The Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services confirmed earlier in June a third meatpacking worker in the state had died. The death was from a Tyson Foods poultry processing plant in Henderson County, Kentucky, where a labor leader with UFCW Local 227 had raised concerns about social distancing in their workplace despite use of masks and plastic barriers.

“They go to work in the meatpacking plant. But when they go home, they’re your neighbors and your friends and your family,” Blair said. “Protecting these workers protects the whole community.”

An analysis from the Food and Environmental Reporting Network found that rural counties with meatpacking plants on average had COVID-19 cases five times higher than other rural counties without plants.

That analysis included two west Kentucky plants with hundreds of cases and two deaths between them: the Tyson Foods poultry processing plant in Henderson County, and a Perdue Farms poultry processing plant in Ohio County.

“In our seven-county district, we’ve, you know, the major driver of the cases that we’ve worked have been facilities in this sector,” said Clay Horton, director of the Green River District Health Department in west Kentucky. “When you look at a business or you look at a major employer, probably one of the larger employers in Ohio County, it’s bound to have an impact.”

Horton and his regional health department have been in close contact with leaders at both plants as outbreaks took hold over the past few months, advising on workplace safety guidance from the state and federal government.

He said that while more data is needed on where cases originate, outbreaks in these plants could be spreading the virus to other people in rural communities, or at the very least driving up reported COVID-19 case numbers in counties where plants are located.

The Green River District Health Department confirmed the first cases of COVID-19 at the Perdue Farms in Ohio County and the Tyson Foods plant in Henderson County on April 6 and April 13, respectively.

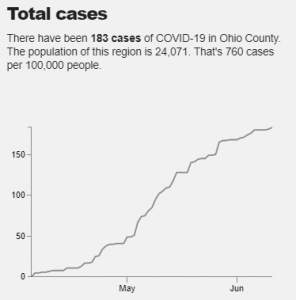

According to the Ohio Valley ReSource’s COVID-19 Tracker, the seven-day average rate of newly reported cases each day began to increase in both counties as outbreaks took hold at the plants.

Ohio County, with a population of about 24,000, has almost twice the rate of coronavirus cases per capita compared to Jefferson County, Kentucky, where Louisville, Kentucky’s most populous city, is located.

Horton’s job to encourage workplace safety in these plants is complicated by federal guidance implying that the authority to temporarily shut down plants due to coronavirus cases should be left up to federal authorities, not state and local health officials.

Horton said he often only has the “power of persuasion” to encourage meatpacking plants to follow optional federal coronavirus safety guidance, with his health department and companies not seeing eye-to-see on some standards.

He said Perdue Farms believed a worker who had no fever but was still showing other COVID-19 symptoms, including coughing, could come back to work. Horton’s department disagreed.

“There have been times during this outbreak that I’ve personally recommended to them that they should probably go above and beyond [federal guidelines], just in light of the number of cases that they were seeing and what we were seeing in terms of spread in the community,” Horton said. “They obviously had a different perspective, and we did all we could to try to persuade them to see [things] that way.”

Jails and Prisons

Meatpacking plants aren’t the only facilities driving COVID-19 infections in rural communities and isolated counties. Jails and prisons, some with overcrowded conditions and tight confines, and nursing homes, with particularly vulnerable populations, have also seen devastating outbreaks in rural counties.

Public health experts on the front lines combating this virus say controlling outbreaks in these types of facilities is critical to protecting rural communities where the chance of COVID-19 spread would otherwise be low.

At one point, soaring cases in Central City, Kentucky, population 5,730, landed the town at the top of a White House report as having one of the country’s highest increases in coronavirus cases over a seven-day period in May, with a spike of 650 percent.

Those cases could be pinpointed to one specific place: Green River Correctional Complex on the outskirts of the town. At least 363 inmates and 51 staff in the prison have tested positive, with many still waiting to be retested for the virus. According to the ReSource COVID-19 Data Tracker, Muhlenberg County, where Central City is located, saw a massive surge in cases in early May, around the time of the White House report.

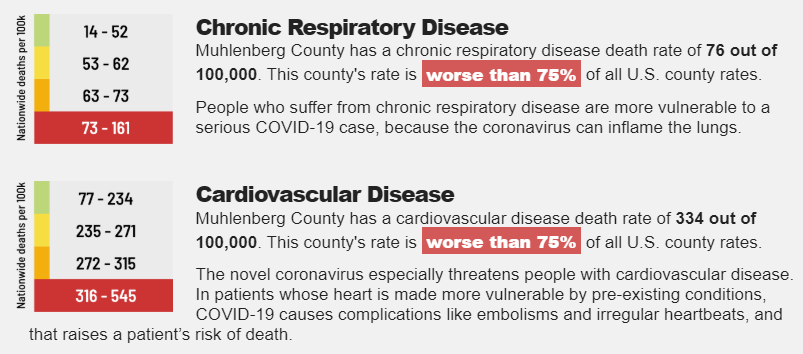

Muhlenberg County’s per capita rate of coronavirus infections is 1615 cases per 100,0000 people, six times the rate for the state as a whole and among the highest of any county in the Ohio Valley. Nearly 1 in 5 people in the county are over the age of 65, and the county ranks among the worst in the country in rates of deaths due to cardiovascular disease and chronic respiratory disease, all risk factors making the population there more vulnerable to the worst effects of COVID-19.

Belmont Correctional Institution in eastern Ohio saw cases spike through mid-May, with at least 66 staffers and 132 inmates testing positive out of almost 2500 housed there. Three of those inmates died.

Belmont County Health Department Deputy Health Commissioner Robert Sproul said about 70 percent of the county’s cases are connected to the prison, with another 20 percent connected to nursing homes in the county.

“It has dorm settings so it’s not individual cells. So these inmates are in close contact, you know, most all day. So the chance of spread is great. Same with a nursing home,” Sproul said. “This spread can happen very easily. So it seems to be more prevalent in those congregated areas.”

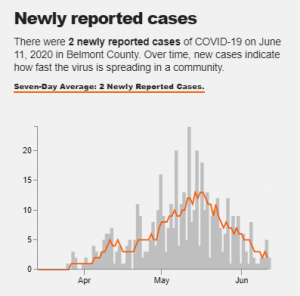

Since the first coronavirus cases were confirmed at Belmont Correctional Institution in mid-April, cases steadily increased in Belmont County through May with a total 462 cases so far, according the ReSource’s COVID-19 Tracker.

Some of Ohio’s other prisons isolated in rural counties have seen skyrocketing outbreaks, with the state corrections department announcing in May it would only test symptomatic inmates and staff despite thousands testing positive after mass testing.

Ohio Department of Health Press Secretary Melanie Amato in a statement said the department has seen cases of meatpacking and nursing home workers spreading COVID-19 to other community members.

Nursing Homes

West Virginia has the smallest population among the Ohio Valley states but its people are among the nation’s most vulnerable to COVID-19 due to underlying health problems. So far coronavirus outbreaks in meatpacking plants and prisons have been limited in the state.

State officials began testing all staff and inmates in state correctional facilities after an outbreak at the Huttonsville Correctional Center in Randolph County. So far that has not found other large outbreaks. Health officials began testing for COVID-19 at a Pilgrim’s Pride poultry plant in Moorefield, West Virginia, after a small bump in cases in the county.

But that hasn’t spared the state from devastating outbreaks in nursing homes.

Clay Marsh, who’s been leading coronavirus protection efforts in the state, said it’s still critical to keep a close eye on these kinds of facilities that could be drivers of outbreaks. Particularly “congregate settings” including nursing homes, where the elderly population is especially vulnerable to the virus.

“In West Virginia, at least the last time I looked, over 50 percent of people that die [from COVID-19] are people that live in this kind of setting,” Marsh said. “The clear issue is that people that work at these facilities, live in the communities, and if there’s community spread, then you can guess at some point somebody is going to introduce that spread into these congregate populations.”

The operators and administrators of nursing homes, meatpacking plants and prisons have all implemented in varying degrees measures to protect against coronavirus spread. Those include testing temperatures when entering facilities, requiring masks and restricting visitation.

Yet Marsh said risk remains as people travel into West Virginia for summer tourism and businesses reopen. And recently another activity has him concerned, as Black Lives Matter protests grow . He said while he supports the demonstrations he would like to see more protesters wear masks and keep their distance from others.

“I love them. But you just see people without masks and crowding. And you almost want to say ‘We still have a pandemic here, you know, this, COVID thing hasn’t gone away,’” Marsh said. “And I think people are distracted right now. Maybe they just got tired of staying inside.”

The ReSource’s Brittany Patterson and Aaron Payne contributed to this story.