The state’s first coronavirus outbreaks began in cities, but the virus spread to rural areas. Recent data shows a disproportionate burden of cases per capita there.

Coronavirus arrived late to Columbus County, but it caught on quickly.

When the rural county’s health department reported its first case on March 28, North Carolina’s overall case tally had already surpassed 900. By May 4, coronavirus in the county reached a new height: 167 known cases, 10 deaths.

Located about an hour from both Fayetteville and Wilmington, the southern North Carolina county has amassed many descriptors over the years: an agricultural center, famous for its festivals and home of the self-proclaimed strawberry capital of the world. It’s also the only county — not city or town — in the United States named after Christopher Columbus outright.

But the county, it seems, has earned another distinction of late. At 296 cases per 100,000 people as of May 4, Columbus has the highest coronavirus rate of all rural counties in the state.

By comparison, some of the state’s most densely populated counties have a lower per capita Covid-19 burden. Mecklenburg County, home to the city of Charlotte and a pandemic “hotspot,” had 159 cases per 100,000 as of May 4. Wake County, which was home to the state’s first case, had 83 cases per 100,000.

Much is still unknown about the pandemic, from the true number of cases in the state to why some areas are hit harder than others. Rural counties, an NC Health News analysis shows, have a lower number of known cases overall, but their per-capita coronavirus rates tend to be higher than in some urban centers. This rural-urban divide follows familiar lines, and it isn’t confined to Columbus County.

The overall coronavirus burden in rural North Carolina counties is 120 cases per 100,000 as of May 4, compared with 113 cases per 100,000 people in metro counties.

Disparities Come Into Focus

It’s no secret that many rural areas lag behind their urban counterparts on health access. People there may live far from a hospital, or have limited access to primary care. Residents of rural areas also tend to be older, sicker and make less money on average.

Coronavirus accentuates these disparities, said Saira Haque, a health data scientist from RTI International, a nonprofit company that has, among other things, worked with the state on coronavirus modeling.

<div class=”flourish-embed flourish-hierarchy” data-src=”visualisation/2255002″ data-url=”https://flo.uri.sh/visualisation/2255002/embed”><script src=”https://public.flourish.studio/resources/embed.js”></script></div>

In Columbus County, some of these factors are crystal clear. The county ranks 96 out of 100 in the state for health outcomes. A quarter of county residents live in poverty and a fifth are seniors, far higher than the state averages on both measures.

Age and congregate setting explain at least some of the cases in Columbus County. More than 80 of the cases in the county come from outbreaks in three nursing homes, said Kim Smith, county public health director.

Rural counties are also more likely to have other settings that can help the virus transmit: farms where migrant workers might live in close quarters and meat processing plants, Haque said.

Some of the hardest-hit rural counties in the state share these characteristics. Sampson County, a farming area, ranks 5th among the state’s rural counties in coronavirus burden per capita. At least one outbreak in Sampson has been reported at a meatpacking facility. Bertie County, which has the second-highest per-capita burden of coronavirus among rural counties in the state, has also had at least one such outbreak.

But there’s a factor that’s even more innate to rural areas and may have helped the virus gain a foothold there, Haque said.

The Perils of Tight-Knit Communities

Smith, the public health director in Columbus County, knows everyone, directly or indirectly. If you live in Columbus County, she says, Smith may have seen you at the grocery store or knows your cousin, mom or next-door neighbor.

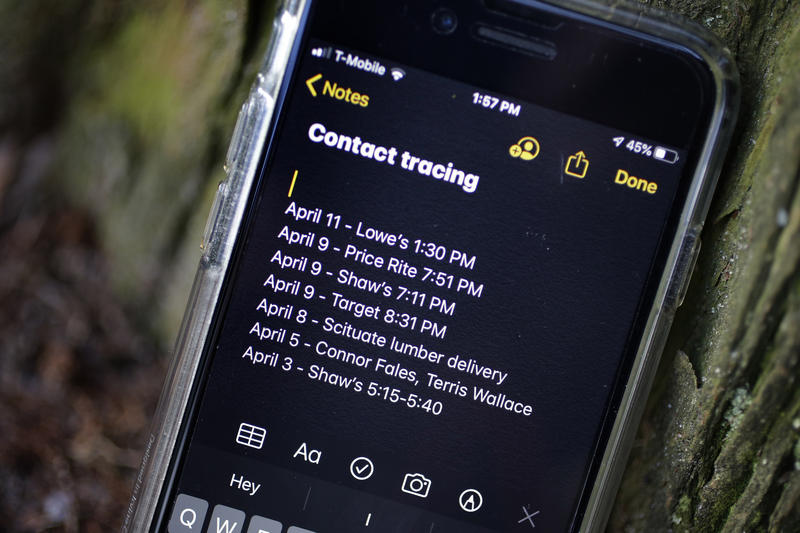

If six degrees of separation is the norm everywhere else, Smith’s world, it seems, is far tighter. It’s a feature the coronavirus contact tracers in her health department employ regularly, she said. If they cannot reach someone by phone, often someone who knows someone can help.

But these tight social connections can also contribute to the transmission of coronavirus, Smith said.

“We’re your typical rural southern community,” she said. “We like to celebrate birthdays and we like to celebrate [people] at funerals and all that takes a lot of people and families and usually that involves shaking hands and hugging and so social distancing goes right out the door.”

At least five cases the county reported in April have been linked to a 50-person funeral that took place the previous month, Smith said.

Officials in the county have done their best to control transmission. The county manager imposed a curfew. Organizers postponed the strawberry festival, an 80-plus year tradition that draws countless people from all over.

But it’s harder to control sporadic neighbor visits and impromptu family gatherings. Contact tracers are aware of this community feature and ask those who tested positive for coronavirus about it.

“We always end by saying ‘Are you sure you’ve not been to a family gathering, a birthday party, a family reunion, a wedding, [or] a funeral?’” she said.

Social distancing in the county, she said, is not as good as she’d like it to be.

Smith’s observation bears out nationally. People living in low-density areas are more likely to attend social gatherings or make visits to friends and family than those who live in high-density areas, a March Gallup poll shows.

It isn’t just about social gatherings, however, said Maggie Sauer, director of the North Carolina Office of Rural Health. People in rural communities are more likely to provide informal caregiving than those living in urban areas, meaning that they come in regular contact with the person they help, potentially increasing exposure to the virus.

Those contacts, regardless of circumstances, have likely contributed to the spread of the virus in rural areas, said Haque, the RTI scientist.

A Resource Conundrum

Responding to coronavirus in a rural area isn’t just a matter of sending the right equipment. It’s about understanding and overcoming the challenges there. For example, Haque said, many rural areas have contended with hospital closures. Over the last 15 years, 11 rural North Carolina hospitals closed, according to the Sheps Center for Health Policy Research at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Sending ventilators to an area where only urgent care facilities remain likely won’t help, Haque said.

“They simply don’t have the staff and they simply don’t have the resources.”

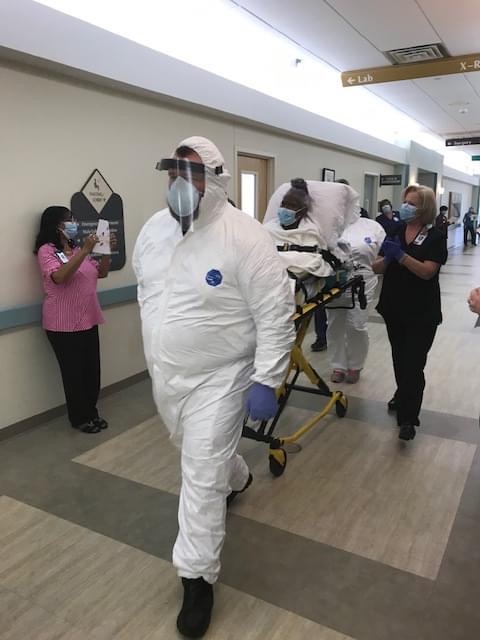

The rural hospitals that manage to remain open may quickly get overwhelmed by the complexity of care that acute Covid-19 requires, Haque said.

Helping rural areas cope with coronavirus outbreaks is about bridging some of those resource gaps, Sauer said. To understand these needs, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services surveyed hospitals and independent primary care clinics in rural areas. The survey showed that rural providers in independent practices had difficulties getting enough personal protective equipment.

Rural hospitals in the state have also had their share of struggles, said Nick Galvez, rural hospital program manager at DHHS. When coronavirus initially emerged in the state, hospitals expected a large surge of patients and as a result canceled elective surgeries to make room. The decline in patient volume and revenue has resulted in furloughs. But rural hospitals are important not only for the people they serve but to support larger hospitals that may need to divert patients in case of a coronavirus surge.

The state health department has taken numerous approaches to tackle some of these challenges from expanding Medicaid telehealth reimbursements to supporting rural providers with additional Medicaid funds. They’ve also worked with grantmakers and federal agencies to help counties secure money for coronavirus-related challenges such as housing homeless people. But the challenges span many aspects of rural life, Sauer said.

“This is not just about health care,” she said. “It’s about housing, it’s about transportation, it’s about food access and all those things.”

These vulnerabilities, which have already been proven to be linked to poorer health in general, can compound the risk for complications from coronavirus. In Columbus County, where the rates of heart disease and diabetes are higher than the state average, preventing coronavirus infections is even more important. Smith said the health department has placed a special emphasis on educating people, including a campaign that involved passing out fliers about social distancing and coronavirus in store parking lots.

As the department continued its outreach and contact tracing, cases in the county have been climbing steadily. By May 6, Columbus County recorded eight more cases and one more death, bringing the new toll to 175 cases and 11 deaths.

Smith didn’t personally know any of those who died, but she’s gotten to know them through weekly check-ins, calls with their loved ones, and contact tracing. When she hears about a death, a thought often crosses her mind.

“I wish I could have actually met [them] in person.”

This article was originally published by the Daily Yonder.