This article was originally published by Ohio Valley ReSource.

“You seen that one with the tombstone up there?” seven-year-old Timothy Easterling asks, looking toward the grass just uphill from his home. “That’s my papaw.”

Timothy’s grandfather Chet Blankenship died in 2016, at age 69. Blankenship lived on land he and his family have long owned at the end of a road atop Bradshaw Mountain in McDowell County, West Virginia. His hand-painted tombstone sits in the grassy patch above the family homes.

Blankenship’s daughter Melissa Easterling now lives in the house next door with her husband, Chauncy Easterling, who grew up on a nearby ridge. They live together with their son Timothy, and usually one or two foster children.

Chet Blankenship died from kidney failure soon after his family started noticing odd colors and smells in their well water. After he died, they got their water tested, and learned that arsenic was among the contaminants that had seeped into their well. The National Institutes of Health links high arsenic exposure to a range of kidney diseases.

The family can’t prove that the arsenic in the water caused Blankenship’s death, and they can’t get firm answers about the contamination in their well and the mining and drilling activity that surrounds their property. But Timothy’s memories of his grandfather reflect the family’s anxiety about the water they depend on.

“One time Chet used it and then he got so sick he just gave up and died, didn’t he?” he asked his mother.

Melissa gently corrected him. “Honey, he didn’t give up. It just — he had to go.”

Timothy thought for a moment, then quietly chimed back in, “He used to be my papaw.”

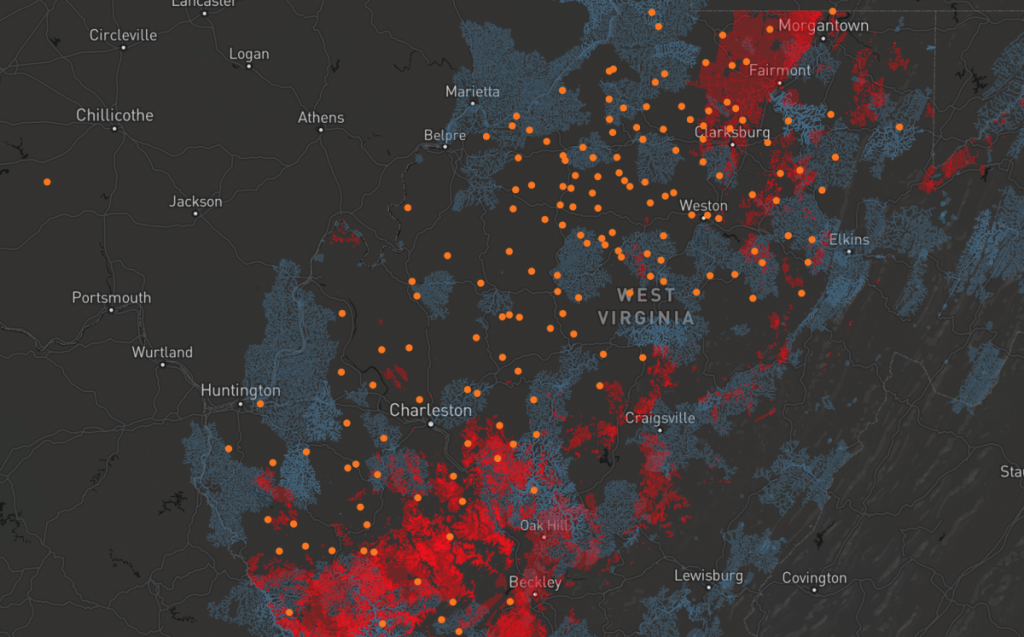

The Easterlings live in the central Appalachian coalfields and much of the land has been mined for miles in every direction. Water runs through the collapsed network of former mines, which may house industrial waste, as well as byproducts from the gas wells that tapped into the methane associated with coal seams.

There are many possible sources of contamination but the family doesn’t know which company might be to blame, or how to hold one accountable to fix the problem, or at least pay for them to get connected to a clean water system. State environmental officials deny there is any evidence connecting the bad water to the mining or drilling nearby. Adding to the family’s frustration, they’ve been asking for a connection to the nearby public water system for years, only to hear that there’s not enough money.

For decades, public water systems in the US have been consistently underfunded, affecting both water access and water quality. EPA records show that in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia alone; there have been more than 130,000 violations reported in the last twenty years. At least 2,000 systems have tested positive for contaminants since 2012. Those statistics only cover people connected to public water systems.

Nationwide, another thirteen million people draw from private wells, and two million people don’t have a reliable source of running water. In areas affected by extraction industry, such as McDowell County, many wells and springs that rural residents are used to relying on are now running dry or showing unsafe levels of contaminants like arsenic and lead.

Struggling for Water

When their water issues started, Chauncy and Melissa contacted the county health department to get their water tested. On seeing the family’s dark brown water, the department referred the family to the state’s Department of Environmental Protection for more advanced testing. The family also had testing done by Appalachian Voices, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group that has been drawing attention to people living with contaminated water. Those tests revealed unsafe levels of arsenic and lead, among other contaminants.

Chauncy and Melissa, together with Willie Dodson of Appalachian Voices, also tested water sources within a few miles of their house. They say they’re yet to find a water source that they trust. The most alarming reading came at a gas well that was drilled into a shallow section of a giant underground mine. It sits right beside the creek that’s below the Easterlings’ home.

That sample showed levels of lead and arsenic even higher than what had shown up in the Easterlings’ well water, along with other contaminants.

Just downstream from that sample site, water from the mine had broken out of the hillside and was flowing into the creek with an oily sheen that left the creek a dingy shade of orange.

More rounds of testing followed, including by scientists from Virginia Tech. The Easterlings say one official told them he suspected coal slurry, a toxic waste product from coal preparation, was the main contaminant, but never gave them any formal documents or test results.

Official comment and documents from the DEP say that there was “no indication that the well was impacted … by mining activity,” because both of the neighboring mines on record were deeper than the bottom of the well. The Easterlings believe that mines and gas wells exist far beyond what’s shown on the records.

The family can sometimes gather enough water from rainfall, using a system Chauncy put together to collect runoff from their roof into a cistern. When there’s a dry spell, Chauncy hauls water, towing a 250 gallon tank behind his pickup truck. Filling and hauling the tank costs the family around $200, and the water is only good for washing and flushing toilets, not for drinking. Since Chauncy works full time, they’ll sometimes have to wait for a weekend before he can fetch water. In the meantime, they have to make do without bathing and doing laundry.

Some of their neighbors, particularly those who are elderly and on fixed incomes, aren’t able to install a rain collection system or haul water. That leaves many of those already in the hardest situations with no alternative to using contaminated water from their wells and springs.

Linda McKinney runs the main food pantry that serves McDowell County. She says that all of the families served are drinking water from unsafe sources. She also sees kidney and liver issues far too often among those families.

The pantry provides bottled drinking water along with food, but they’re not able to fully meet the families’ needs. The food pantry recently received a donation of hydro-panels, which use solar energy to condense water moisture from the air. McKinney hopes that will help narrow the gap between what her team is able to provide and the need for clean water among the families they serve.

Widespread Issue

I’ve reported on water issues since 2016, mainly in the central Appalachian coalfields. The most glaring water problem I covered was in Martin County, Kentucky, where residents complained about possible exposure to health risks due to extremely leaky pipes and a lack of communication around water outages.

Martin County’s many-layered water problems started to get national attention and significant outside funding. But the $5 million now heading for Martin County is a drop in the bucket compared to the more than $600 million in water infrastructure needs that exist just in Appalachian Kentucky, according to a study from the Kentucky Infrastructure Authority. That includes $28 million for Letcher County, where I live, and where a third of the residents have no option for connecting to a public water system, according to the same study.

The federal government estimates that $472 billion in water investments are needed across the country in the next twenty years. If you break that down to one year, it’s a bit over $23 billion.

In recent history, the most the federal government has allocated toward water system infrastructure was $7.7 billion in 2009, as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Every other year since at least 1995, the amount has been less than $3 billion, even though the government’s own assessments have always shown an average annual need of at least $12 billion.

In reporting on Martin County I spoke repeatedly with Nina McCoy, a retired science teacher who, together with her husband Mickey, has played a prominent role in water testing and advocating for local water protection since at least 2000. That’s when a coal slurry impoundment broke through an underground mine shaft and sent a flood of sludge roaring down multiple creeks in Martin County, poisoning miles of streams.

McCoy says that in recent years, she’s seen a shift in local thinking and national awareness. She recalls that when neighbors without water in Martin County first saw TV coverage of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, “It was like, oh my gosh, there are other people who have water problems.”

McCoy now believes that any real solution will have to come from solidarity among communities whose water has been impacted. “We all need to get together on this, because this is a problem nationwide.”

The kinds and causes of America’s drinking water crises are widely varied, but extractive industry is a common thread. On a reporting trip to a coal mining region of the Navajo Nation, near Black Mesa, Arizona, I learned that while rain has long been scarce in the area, there used to be reliable sources of groundwater. Windmill-powered water wells dot the landscape, but many of them have run dry. Since coal mines opened on Black Mesa and started using large amounts of water to pump coal to a power plant, many wells and springs have run dry.

The mines and power plant recently closed, but it will still take years for the groundwater to recharge. In the meantime, rural residents have to pay to haul water from a well in town that taps into a deeper layer of groundwater. That water can be used for crops and livestock but not for human consumption. Drinking water has to be bought or brought in from elsewhere.

Nicole Horseherder is a resident of Black Mesa and founder of the community organization Tó Nizhóní Ání, which translates roughly to “clean water speaks.” She has seen the springs on her land dry up, making it harder and more expensive to keep livestock. Her fears though are mainly for the future.

“What’s going to be here in 20 years?” she asked. “If it’s not going to be here and it’s a life-giving element, there’s going to be no life here.”

Watershed Moments

Many residents in affected communities feel there’s a special injustice to situations like these, where clean water hadn’t been a problem until extractive industries took a toll.

Melissa Easterling said that growing up in McDowell County, good water was plentiful. High tables of clear groundwater flowed from abundant springs and streams. Her family and neighbors didn’t need to worry about water infrastructure. She suspects that as the used-up mines were allowed to flood, the water table sank. And now, she fears, the residue of coal and gas extraction seems to have left the water contaminated.

The Easterlings live at the end of Emerald Ridge. Looking south, the next ridgeline marks the state line with Virginia. To the north, down below, is a wooded valley carved by Panther Creek. The creek flows on into Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River, which marks the state line with Kentucky.

The area surrounding Panther Creek was long known as Panther State Forest and is now a wildlife management area meant for hunting and fishing. Chauncy says it was once an extremely popular fishing spot, but he and other locals have long stopped going there because of contamination fears.

Staff at Panther WMA say that water wells in the park are tested regularly, and haven’t shown any excessive levels of contaminants. They still stock the creek for fishing, and grow gardens to attract deer for hunters. The park still feels wild and healthy, though you’re likely to come across more gas wells and pipelines than other visitors.

Looking downstream from where dirty mine water flows into the creek, Chauncy lamented what’s been lost. “We used to drink the water out of that creek. Now you can’t do it. It’s contaminated.”

He worries for the future. “God knows our children’s children won’t be able to swim in that creek or play in that creek or fish in that creek.”

Water System Woes

The McDowell County water system has a line that runs up Bradshaw Mountain, and it reaches some of the families whose wells have dried up or been contaminated, but it stops a mile short of the Easterlings’ home. The family has been trying to get connected for eight years, but there’s still no money for the project, which would take years more to complete even once funding is found.

Much of the water infrastructure in McDowell County was installed by coal companies for their workers when the industry was booming. But coal production has been declining in McDowell County since the 1940s. Many water systems were abandoned as the mines closed, and were then neglected for decades.

A county-wide public service district was created to take over the systems with the intention to maintain, update, and expand them. The problem is, there hasn’t been enough money. Federal funding, once provided through grants, was largely converted to loans. The McDowell PSD now has $34,000 in monthly debt payments and can’t afford to take more loans, according to General Manager Mavis Brewster.

“You don’t want to keep raising rates,” Brewster said. “A lot of the residents in McDowell County are elderly, they’re on fixed incomes, and water’s a basic need. You have to have that.”

Brewster said the PSD has some momentum toward expanding water services in the county. They’ve cobbled together what they can from state and federal agencies, but there’s nowhere near enough funding to meet their needs.

Top priorities for construction this spring are for the towns of Keystone and Coalwood.

In Keystone, the risk of bacterial contamination is high enough that since 2012 residents have been under a continual advisory to boil their water for safety. Coalwood, where the PSD is located, is slated to be the first area covered by a new sewage treatment system. Three towns in McDowell County — Welch, War, and Bradshaw — have their own sewage treatment systems, but none of the 3,300 customers served by McDowell PSD have sewer service.

Brewster says some of the communities have pipes that collect sewage but then send it straight into the nearest river or creek. That’s been the situation in Coalwood, but even that system has deteriorated further since the coal company that built it pulled out and stopped maintaining it. The collection network has issues with clogging and backing up, flooding homes with sewage.

Neighbors in Need

Chauncy and Melissa have been asking questions of old-timers among their neighbors, with special interest in ones who’d worked in the mine below their water table. Among them, Chauncy recounted, were at least a couple who have since died, and who said they never would have worked in that mine if they’d known it could poison their own water.

One neighbor whose water contains high levels of lead and arsenic is suing a coal company, and also fighting to get any damages covered by her homeowner’s insurance. She’s shared photos of severe rashes and chemical burns that she claims came from exposure to the water.

Chauncy and Melissa say they wish they knew who they could sue, but there are too many companies involved in the mines and gas wells around them to know who to hold accountable, especially since many of the operations have complicated corporate histories.

Outside Owners

Chauncy Easterling says it’s his understanding that most of the people who own the local coal and gas operations live in distant cities. “Chicago, New York, places like that,” he explains. “I’d like to see them come in here and clean it up. I’d say they ain’t even rich enough to fix what damage has already been done.”

He said those same companies often own the land that many many of his neighbors rent, which is one reason that many are afraid to speak out. People are worried that they’ll get evicted or have their property condemned.

These concerns about absentee land ownership are woven into the roots of many of the region’s problems.

In 1979, teams of academics, community organizations, and local individuals across Appalachia worked together to conduct a land ownership study. Large landowners were assessed in eighty counties across six states. The study revealed high proportions of absentee corporate owners, often paying low tax rates on their holdings.

In McDowell County, for example, more than three-quarters of the land and more than 90% of the mineral rights were held by absentee owners at the time. The five largest owners included a range of timber and mining companies, all based in other states.

A new land study is currently in development, and organizers are seeking funding to do an updated survey of land and mineral ownership in Appalachia.

Based on what records are available, it seems the overall picture has stayed the same. Outside companies own large amounts of Appalachia’s land and resources. The business model is extractive not just in taking fossil fuels out of the ground, but also in taking wealth away from the region.

With little local control over the land, widely depleted sources of natural wealth, a range of work and environment-related health issues, it’s no wonder that so many Appalachian communities are struggling to build new economies and keep themselves afloat.

Funding Prospects

President Donald J. Trump campaigned with promises of major infrastructure spending, and the White House has frequently touted “Infrastructure Week” initiatives. But so far those have not resulted in major new projects or funding. The topic has since faded from prominence among the president’s talking points.

Prominent Democrats have called for a “Green New Deal” to include massive infrastructure spending, including on water systems. The Green New Deal bill introduced by New York Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez last year would “guarantee universal access to clean water,” but some fellow Democrats question the bill’s costs and the legislation faces stiff Republican opposition.

More immediately, coalfield communities have been focused on getting funding from the federal Abandoned Mine Land Fund, which is supported by a fee on coal companies and used to fix damages caused before enactment of the Surface Mining Control and Regulation Act.

A bipartisan proposal known as the RECLAIM Act would speed the rate of spending that AML money and expand the scope of funding to include projects like water infrastructure that can help communities and their economies. A few pilot projects following a similar model have been included in recent federal budgets.

What’s Underground

The Easterlings say they’ve never sold their mineral rights, so no mining company should have had the right to mine beneath their home. But core samples drilled deep from the earth show that the coal had been mined underneath them anyway. The family somewhat expected this, having seen dishes fall out of the cabinet from shakes and jolts when, they presume, pillars were being pulled in a mineshaft below them, allowing the cavity to collapse. Chauncy says this kind of “robbing coal” is commonplace. “It’s underground. It’s out of sight, out of mind.”

The collapsed coal seams have been punctured by gas wells. No one knows what’s still in the old mine voids. From scouting around the mine entrances and talking to friends who used to work in the mines, Chauncy and Melissa have come to believe it’s likely that heavy equipment, batteries, and other industrial trash was left behind in the mine. They’re also concerned that refuse from a coal washing plant — a dark toxic sludge known as slurry — might have been pumped into the abandoned mine, which is a common practice for disposing of the waste. There’s no official record of slurry being injected in the area, but the Easterlings have heard that the mine below them was used for dumping by a nearby coal washing plant.

There have also been dozens of gas wells drilled near this web of mines. Some older gas wells don’t show up on official maps because they were not properly permitted or have no identifiable owner.

Some of the wells in the area are from conventional drilling but records show others used fracking, which pumps water and chemicals into the ground, opening up cracks from which gas can be drawn.

Once a well stops producing it is supposed to be sealed. But at least some of the older wells around the Easterlings were left unplugged, with just an abandoned pipe sticking out of the ground.

The Easterlings say that their water started to change soon after nearby gas wells were shut down. At first the water started to smell, then little bits of dark rock dust appeared, and then before long it was running dark brown.

Chauncy worked for years as a miner and then as a boss in underground coal mines. He says it wasn’t unusual for the mine to run into an area that had already been mined even though it was outside any other mine’s permit boundary.

Once, he said, a crew working under him cut into a gas well which hadn’t been on any of their maps. He and Melissa both remember that as a terrifying time. But shades of fear color much of Chauncy’s memories of working underground. Coal miners get paid not just to produce coal, but to regularly put themselves in danger.

Given today’s record rates of severe black lung disease, it’s no exaggeration to say Chauncy and other miners have been getting paid to accept that their lungs will likely get scarred by coal and rock dust.

Chauncy took a buyout offer in 2013, partly because his health and breathing had started to noticeably decline. The buyout came with six months of severance pay, which he used to get certified as a commercial truck driver. He’s applied for black lung compensation, but was told it may be five years before he’d start receiving any benefits.

Chauncy got out of the mines, but he and his family still fear for their health. Their home is surrounded by remnants of fossil fuel extraction and the lasting legacy of environmental degradation.

This story was made possible with funding from the Abrams Foundation, the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University, and the Solutions Journalism Network.