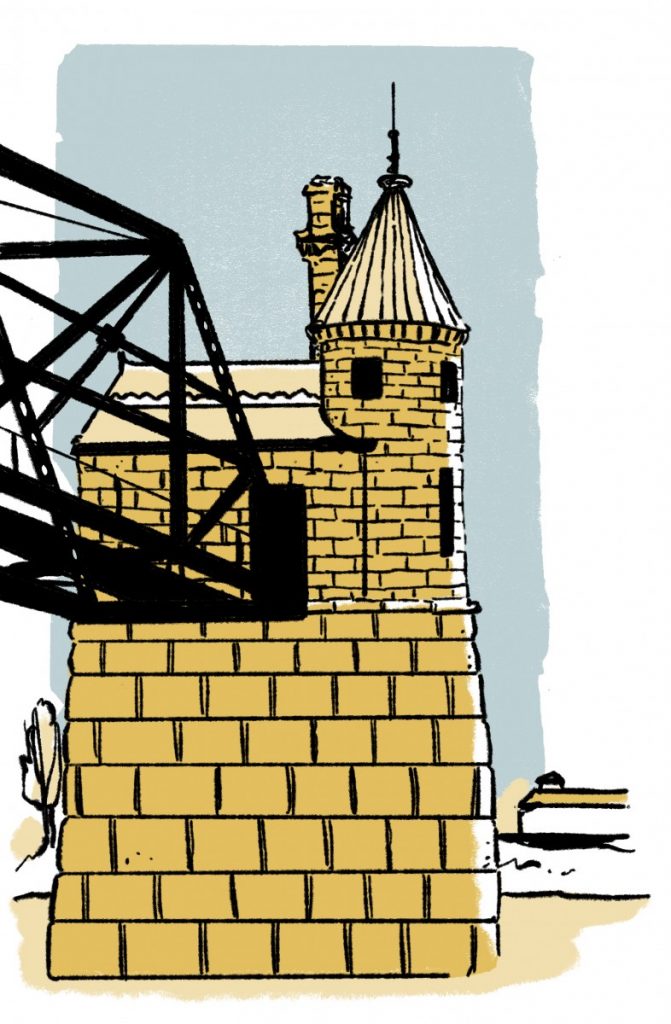

I live in Mount Washington, on the east side of Cincinnati, roughly the midpoint of the 981-mile Ohio River. Below us, near the mouth of the Little Miami River, marinas, barge terminals and Cincinnati Water Works’ Miller Treatment Plant line the river’s bank. The Water Works has these old red-roofed castles on both the Ohio and Kentucky sides that seem to stand sentinel over the water. The plant draws 88% of Cincinnati’s water from the Ohio. Next door to the Water Works lies a long building, low in profile like a Civil War ironclad. It’s easy to miss as you follow Route 52, the Ohio River Scenic Byway. This is the headquarters of a little-known organization that saved the Ohio River’s life.

The Ohio River Valley Water Sanitary Commission, or ORSANCO, is comprised of eight states in the Ohio River watershed: Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia. ORSANCO was formed in 1948 to solve the boundary-thwarting problem of water pollution across state lines.

At the time, the river was an embarrassment and a hazard. The Ohio was one of the most industrialized watersheds in the country, and by the 1930s, 60 sewer outfalls in Cincinnati alone fouled the river with an estimated 350 million annual tons of untreated sewage. This continued into the 1940s. People were getting sick.

Something needed to be done, but industry stood staunchly opposed to regulation. The river found an unlikely champion in the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce. In spring 1934, at the end of a civic beautification committee meeting, Hudson Biery, public relations director for the Cincinnati Street Railway Company, stood up. While we are cleaning up the city, he suggested, why not clean up the river, too? “The citizens of Cincinnati don’t need to be reminded every time asparagus is served for dinner in Pittsburgh.”

William F. Wiley, militant editor of the Cincinnati Enquirer, which had long been publishing articles decrying the river’s state, got behind Biery and the Cincinnati Stream Pollution Committee was soon formed. This was the seed, nurtured by like-minded individuals and organizations throughout the Ohio River Valley, that grew into ORSANCO.

They knew they would only succeed through a partnership that included all of the Ohio River Valley states, but they started local, earning regional support. ORSANCO’s design as an interstate agreement was further encouraged by a federal government that favored regional solutions to pollution. Looking back, Biery suggested that it was backing from the business community that had helped break industry’s blockade against such an idea.

The chamber’s initiative gained county-wide support, and was soon matched on the other side of the river by the Covington (Kentucky) Chamber of Commerce’s creation of a sanitary district. While most agreed that an interstate agreement was the way to go, what that agreement looked like would take years to iron out. Progress stalled with World War II, during which the river’s state worsened. Proposals were drafted, haggled over and finally signed.

As ORSANCO got to work, pushing for municipalities throughout the valley to invest in treatment plants, the results were almost immediate. Before ORSANCO, less than 1% of the sewage generated along the river received treatment. Just 18 years later, 99% of it went through treatment plants. By 1965, 90% of the 1,705 industrial establishments along the river’s length complied with ORSANCO’s minimum industrial waste requirements.

ORSANCO is still going. These days, it monitors the river at locks, dams and tributaries for metals, radiation, chemicals and biologicals. Their biologists are out there every summer, electrically stunning and counting fish for the largest river fishery dataset in existence.

Key to my health — and yours, if you live in a municipality along the Ohio’s banks — is their source water protection program, through which ORSANCO partners with drinking water utilities. For example, ORSANCO operates an organic compound detection system, which monitors around the clock for spills. When one occurs, ORSANCO staff track, model and share information with downstream water utilities. ORSANCO also sets pollution control standards for levels of contaminants, based on their impairment of four essential uses of the river: drinking and industrial water supply, recreation and habitat for fish and wildlife.

A few years ago, ORSANCO’s board of commissioners flirted with eliminating its pollution control standards. The reason, according to ORSANCO Chief Engineer and Executive Director Richard Harrison, is that the Clean Water Act had developed to a point that some people on the commission felt there were now redundancies between ORSANCO and the federal act — and that this entailed altogether too much regulation. “The thought that you can put everything in a regulatory arena and have the same level of investment in infrastructure replacement just isn’t accurate,” he said.

ORSANCO embarked on a multi-year review process that resulted in June 2019 with the decision to revise those standards to allow for “greater flexibility” among its member states. There was immediate blowback. Over three public sessions, four hearings and multiple webinars, the commission received more than 10,000 comments, almost all of them against revising the standards it had long set. It’s the word “flexibility” that vexes many concerned citizens who worry it removes a much-needed check on polluters.

The news came at what felt like a bad time for the Ohio River. Cincinnati’s “Bill Keating Jr. Great Ohio Swim,” the only open water swim across the Ohio and back, was canceled in October due to a harmful algal bloom (HAB). The Trump administration’s repeal of Obama-era protections of drinking water supplies was ringing in my ears. And for the umpteenth year running, the Ohio River had been listed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [EPA] as the dirtiest river in America based on raw tonnage of emissions.

ORSANCO’s seemingly softened stance felt like a steadfast defender of our river had put down its sword.

Harrison told me the recent revision doesn’t in any way change its mission to protect the four uses of the river. And while the compact grants the commission authority to “issue orders on any entity discharging sewage or industrial waste,” per the ORSANCO agreement, it falls to the states to actually enact legislation necessary to maintain their Ohio River waters according to the standards. In practice, enforcement happens through the EPA, which publishes its own water quality standards, and the National Pollutants Discharge Elimination System, which is part of the Clean Water Act.

Tom Fitzgerald, a federally appointed ORSANCO commissioner and director of the Kentucky Resources Council, was a voice of both dissent and compromise in the revision process. The latest review of the pollution control standards revealed that one state, Illinois, wasn’t applying any of ORSANCO’s standards to its discharge permitting and another, Ohio, was only using some of them, he explained. (Ohio has since moved to implement them.) Some ORSANCO commissioners argued that the discrepancy in application of the standards was leading to undue confusion.

“The reality is there’s no mechanism in those pollution control standards or in the compact to compel a member state to use the standards,” Fitzgerald told me. For ORSANCO to compel any one of the member states to comply would be unlikely, given that it requires a vote from two out of three of the commissioners appointed by each of the states, including the offending state. And for ORSANCO to force compliance on one of its member states would have a corrosive effect, he said, jeopardizing by extension the other vital roles ORSANCO fills.

But outright elimination of these historically agreed-upon standards “would have sent entirely the wrong message at a time when the science behind pollution control and the premise that you don’t compromise public health for economic considerations are under attack,” and when the EPA’s standards are being delayed, repealed and otherwise revised, Fitzgerald said. “I think that for ORSANCO to have signaled a retreat on water quality would have been devastating.”

The muddy Ohio was unusually clear at Cincinnati this year. Near the banks you could actually see the bottom. But pretty quickly, a green film of algae formed in the water. As the date of the “Bill Keating Jr. Great Ohio Swim” approached, Miriam Wise was paying close attention to E.coli and harmful algae levels in ORSANCO’s weekly water quality reports. Wise works for Adventure Crew, the nonprofit that organizes the swim. Adventure Crew hoped conditions would change, that the HAB would drift downstream. When it didn’t, they canceled the swim. That’s a shame, Wise said, because registrations for the event have been on the rise. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources has also seen increased registration for kayaks and canoes. People are flocking back to the river, which feeds back into a wellspring of support.

The Ohio River Paddlefest, which Wise also organizes, wasn’t canceled. This August event is the largest group paddle in the nation. The Ohio is closed to motorized and barge traffic for an en masse 10-mile float. As usual, thousands turned out. Kayaks and canoes spread across the mile-wide river in a bright flotilla. Wise said the event reconnects people with the river, which they then share, counteracting the bad rap for “the most valuable natural resource in the region,” she said.

During the summer, Brewster Rhoads, who founded the Ohio River Paddlefest, swims in the river about five times a week from the Ohio River Launch Club, where he moors his steel, motorless double-decker Kelly houseboat. Rhoads has lived in Mount Washington much longer than me — since the 1980s — but like me, his preferred route into the city follows the water. Over the decades, he’s watched that neighborhood, Cincinnati’s historic East End, transform as Mom and Pop shops close with the departure of residents whose livelihoods were tied to the river. This was the center of Cincinnati’s booming steamboat industry. Steamboat captains lived here, he said. And a couple of grand (if dilapidated) old dames still stand there, with high turret rooms that take in the broad sweep of water.

Photographers Charles Fontayne and William S. Porter captured the history of this place in their first panorama of an American city: “Daguerrotype View of Cincinnati.” The image was taken from a Newport, Kentucky rooftop in September 1848, almost exactly a century before the ORSANCO compact was signed in Cincinnati.

This length of bank is shown in the eighth and final plate of the series. It’s a diagonal shot across the upriver water. Dozens of silvery sternwheelers stand along the banks at what was then called Fulton, named for the inventor of the commercial steamboat. Timber and industrial detritus tumble into the river beneath smoke-shrouded, denuded hills. In the foreground, just off the Kentucky shore, a man drives his horse and cart in the shallows. Held up to the present, it completes a picture of how deeply we have relied on this waterway, how hard we have used it. How central it was and will always be to the landscape and communities through which it wends.

Our present economic connection to the river is no less real, but easier to overlook. Energy generated along its banks travels over high-tension lines from rural power stations. Riverside utilities and industries are boxed in behind high levees and fencing.

Meanwhile, in that familiar succession of neighborhoods, the old riverside villages are being replaced by new communities for those who can afford a premium river view. In downtown Cincinnati, as in many river cities, millions are being invested in riverfront development that draws on the beauty and sense of place only a river can provide. The shift from industrial to commercial and residential is probably good for the river’s overall ecology, Rhoads thinks. And while location alone doesn’t connect you with the river the way swimming or paddling these waters will, those new water-facing windows have potential to build what Rhoads calls “a constituency of concern for the health of the river.”

So if ORSANCO was never an enforcer, how did it manage to accomplish so much? And what does that say about its the future?

Edward J. Cleary, ORSANCO’s first director, believed the commission’s success lay in its appeal to the ultimate authority on the fate of the river: public opinion. From the beginning, it mounted PR and community action campaigns in some 3,000 riverside cities and towns, made films, held rallies, all of which garnered citizen support at the ballot box for the bond issues that primarily financed water-treatment infrastructure. In “The ORSANCO Story: Water Quality Management in the Ohio Valley,” Cleary, an engineer, writer and former employee of Thomas Edison, estimated the project came out to an average price of about $100 per capita across the Ohio River Valley.

ORSANCO is still waging a PR campaign for a river that many, including environmental activists, say still has an image problem: its designation as the most polluted waterway in America, based on the EPA’s annual toxic inventory report.

News reports touting those numbers do the river a disservice, Harrison said, because they don’t account for overall volume, flow and other factors like where discharges occur. Under normal flow conditions, he said, from a bacterial standpoint the river is safe for recreation. “When you look at the Ohio River Sweep [the annual volunteer-powered cleanup ORSANCO organizes along the river’s entire length], when you look at the Ohio River Recreation Trail, and at the Great Ohio River Swim, these are all events that show that in actuality the river is in amazing condition.”

In the coming years, ORSANCO must adapt, developing programs to guard against emerging contaminants with difficult-to-pronounce names, even as it tracks legacy pollutants and residual damage from mining and industry past. Next year, Harrison told me, they will be partnering with the EPA on sampling for perfluorinated compounds, or PFAS, which are the focus of lawsuits against DuPont for releasing them into the Ohio. HABs, like the one in 2019 that covered 300 miles of river or a 2015 bloom that covered 700 miles, are a complex new threat to health, by no means unique to the Ohio River Valley.

And then there’s a past that threatens to return. “There’s the issue of the viability of small drinking water and wastewater systems,” Fitzgerald said. “You know we almost have two worlds out there. We have those cities and those communities that can afford safe and reliable treatment and we have those systems that have failing or close-to-failing drinking water systems.”

A river as powerful and important as the Ohio lays the groundwork for many possible futures. ORSANCO, it seems, has a role in all of them. There’s just too much at stake. It’s essential for all the river’s users to sit at the table, because the more eyes on the river, the better.

Cedric Rose, a freelance writer for Belt Magazine, authored this story. He can be reached at [email protected].

Good River: Stories of the Ohio is a series about the environment, economy and culture of the Ohio River watershed, produced by seven nonprofit newsrooms. To see more, please visit ohiowatershed.org.