In Appalachia, organizations like seed libraries and community gardens are helping to save traditional heirloom vegetables from being lost. Sometimes, the seeds are found in unexpected places like when Travis Birdsell visited the barn of an Ashe County farmer in 2017.

There, he found tomato seeds smeared on the side of an old grocery store sack.

“All the words said were ‘Big Red,’” Birdsell said.

“Big Red” ended up being an Oxheart tomato, an heirloom variety known for its huge size. Each tomato can weigh up to 2.5 pounds, making them more than four times the size of the average grocery store tomato. Before the tomatoes are even fully grown, they’re heavy enough to bend their stalks.

Birdsell knew he wanted to plant the seeds, but when he did, only one germinated. That single seed, though, was enough for him to successfully grow the tomato in 2019.

The seed was planted in the Ashe County Victory Garden. It’s located in downtown Jefferson, North Carolina. Birdsell, the Ashe County Cooperative Extension director, has used the garden since 2016 as a space to grow and reintroduce heirloom vegetable varieties in southern Appalachia.

Each seed has a special origin story, but right now, the Oxheart tomato is the star — it’s enormous, of course, and Birsell said it has a meaty texture.

Varieties like the Oxheart tomato are kept alive thanks to the work of seed savers. The work they do throughout Appalachia is crucial in keeping heirloom varieties on our tables and in our bellies.

Seed saving is especially important in communities like Ashe County. Agriculture has always been the main industry, and local families have been able to keep certain varieties around for decades. Birdsell said he hopes the Victory Garden highlights that.

“We want to play into the culture that’s alive and well in southern Appalachia, which is independence. This is a way to tap into food independence.”

A Radical Idea

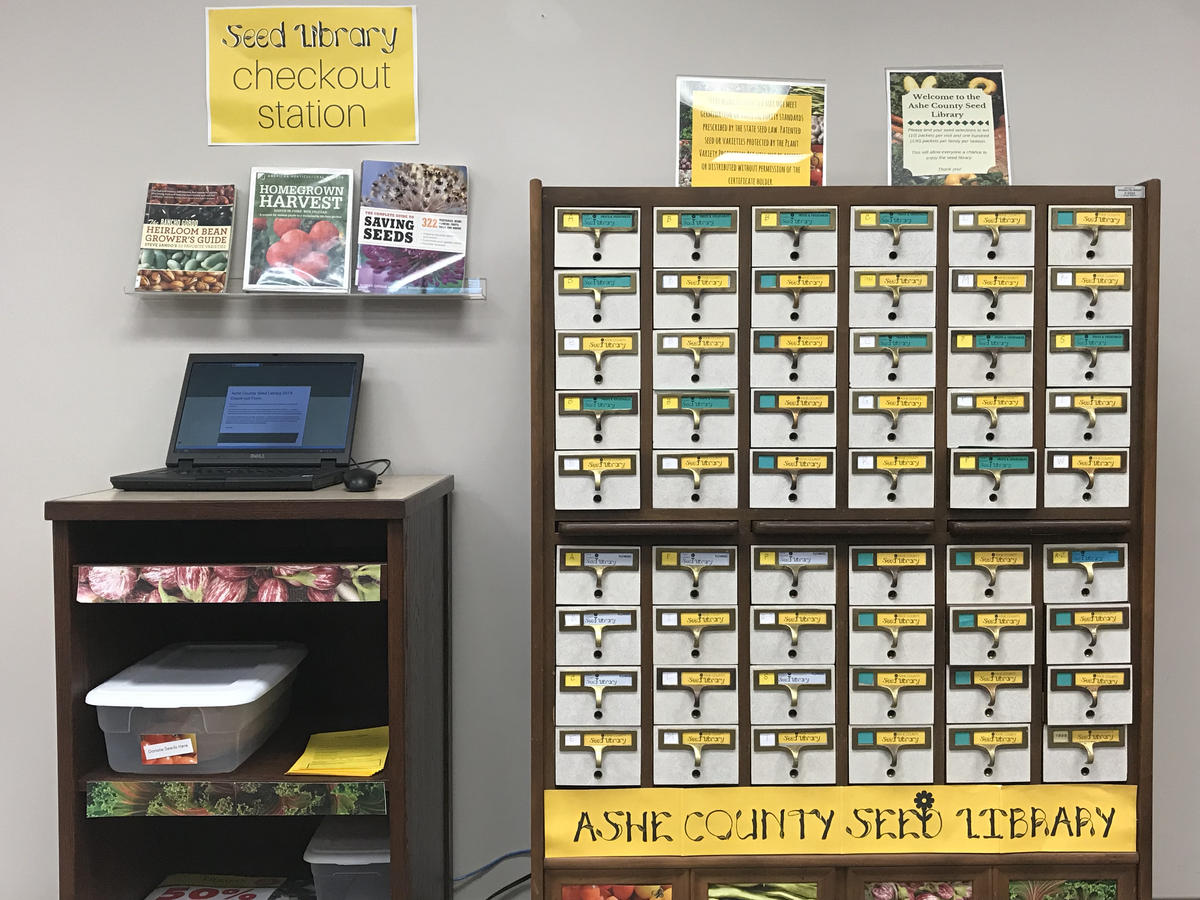

Getting seeds into the hands of home gardeners is a key part of that self sufficiency. In 2019, Birdsell produced enough of the Oxheart tomatoes to make seeds available to the public, through the Ashe County Seed Library, which is about a mile up the road from the garden in West Jefferson, North Carolina.

The seed library is on the second floor of the public library and is housed in an old card catalogue cabinet. The drawers are stuffed with dozens of varieties of seeds. There are beans, tomatoes, greens and even flowers.

Each tiny manila envelope contains about a dozen seeds. Heirloom beans and tomatoes are among the most popular. Librarians ask that people try to save a few seeds, so they can continue to stock them next year. There are also handouts that describe the seed saving process for nearly every kind of seed in the library.

Beans can be left on the vine until the shells are dry. Then, the seeds can be removed and stored in a jar until next year. Tomatoes are a bit trickier. Some people dry the seeds on a piece of wax paper so they’re easy to remove, and others put seeds in a jar and cover them with water. The good seeds float to the top, and the others stay at the bottom.

All the seeds at the Ashe County Seed Library are free. There’s no formal check-out process, and you don’t even need a library card. And when the cost of heirloom seeds can sometimes be more than $4 in stores, it can seem like a radical idea to give them away.

“I think it’s liberating to be able to provide for yourself and being able to access free seeds is the start of that process,” Birdsell said.

A Lost Art

Some of these seeds in the Ashe County Seed Library have been saved by local families like Vida Belvin’s for generations.

Her brother donated a special variety of pole bean that’s been a staple in their family since the 1920s. She calls it the Six Week Bean. It’s a flat green bean and you can get up to two harvests a year with it — more than a traditional green bean.

Blevins and her brother learned to save seeds from their parents. Their mom, Kada Owen McNeill, has lived in Ashe County for a century. McNeill was the 7th child of 12. She grew up on a family farm, just a few miles north of Jefferson.

They grew and preserved most of the food they ate. McNeill remembers giant, 65 gallon barrels of sauerkraut that her family would make and share with their neighbors. And, to save money, they spent many hours at the end of each season saving seeds.

McNeill grew up during the Great Depression. Then, saving seed was a necessity. Because you couldn’t just run out and buy them at the store. They saved seeds for apples, cabbage and parsnips. Her dad even built a small room specifically for drying pumpkin and apple seeds. She taught her daughter to save seeds too.

“I think it’s kind of a lost art now,” Blevins said.

Seed saving may be less common than it was a few decades ago, but it can still have the power to shape entire communities, Sarah Harrison said, who donated seeds to the Ashe County Seed Library through the Seeds of Resilience Project at Appalachian State University.

“Seeds are so important. We don’t really think about it that much, but one simple seed can produce a plant that can produce hundreds of more seeds, which can feed a whole community,” Harrison said.

According to experts like Chris Smith, the executive director of the Utopian Seed Project, based in Asheville, North Carolina, the cost of losing these seeds could be devastating for Appalachian communities down the road.

Smith said that seed saving helps build ecological resilience. Because if we only have a handful of different types of tomatoes or types of beans, we aren’t as adaptable as we would be if we have hundreds of different types of heirloom seeds kept somewhere safe. As a researcher, he said that genetic diversity in seeds is key for a sustainable, resilient future.

“If we’re saving our own seeds, in our own regions, then what we see is crop adaptability from season to season,” Smith said.

And the seeds that have grown here in this climate for hundreds, sometimes thousands of years are simply better adapted to southern Appalachia than most of the seeds you can buy in the store.

This story was originally published by West Virginia Public Broadcasting. It is part of the Inside Appalachia Folkways Reporting Project, a partnership with West Virginia Public Broadcasting’s Inside Appalachia and the Folklife Program of the West Virginia Humanities Council. The Folkways Reporting Project is made possible in part with support from Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies to the West Virginia Public Broadcasting Foundation. Subscribe to the podcast to hear more stories of Appalachian folklife, arts, and culture.